How to Regulate Stablecoins

Cryptocurrency markets are rallying to new highs. Simultaneously, another type of cryptoasset is gaining relevance: stablecoins. Unlike Bitcoin & Co, stablecoins aim to maintain a steady value against a national currency. They facilitate trade on cryptoexchanges, underpin the DeFi ecosystem and promise to be a stable store of value. Unregulated, however, they come with significant risks. KOF economists Hugo van Buggenum, Hans Gersbach and Sebastian Zelzner discuss regulatory measures.

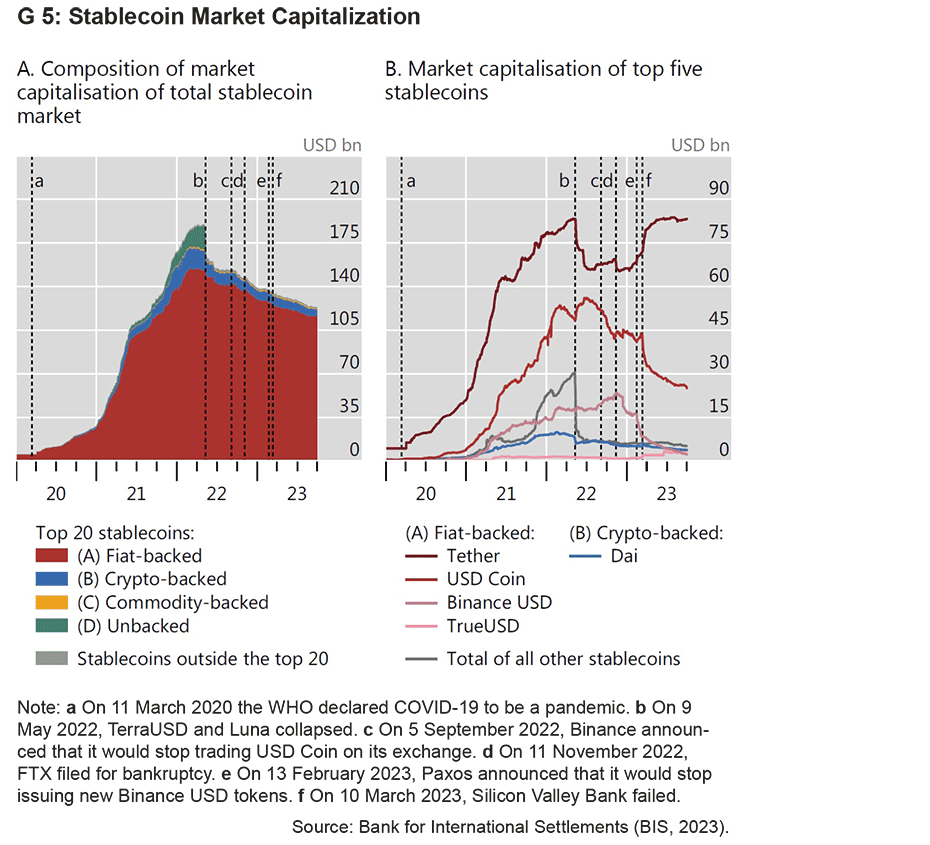

Stablecoins are a digital, privately created money-like asset. They aim to maintain a stable value, typically against a national currency. To achieve this goal, they are typically backed by cash-like assets denominated in that currency. Chart G 5, panel A, shows that in 2023 such ‘fiat-backed’ stablecoins accounted for about 95 per cent of the total stablecoin market. The two largest stablecoins, Tether and USDC (panel B), are pegged one-to-one to the US dollar and invest in liquid, dollar-denominated assets to maintain their peg.

Stablecoins started to rapidly gain popularity in 2021. Their market capitalisation peaked at almost USD 200 billion at the beginning of 2022 – just before the crash of the Terra/Luna stablecoin and the collapse of the FTX cryptoexchange led to a crisis of confidence (chart G 5, panel A). Stablecoins have been on the rise again more recently – in March 2024 they re-approached a total market capitalisation of USD 150 billion.

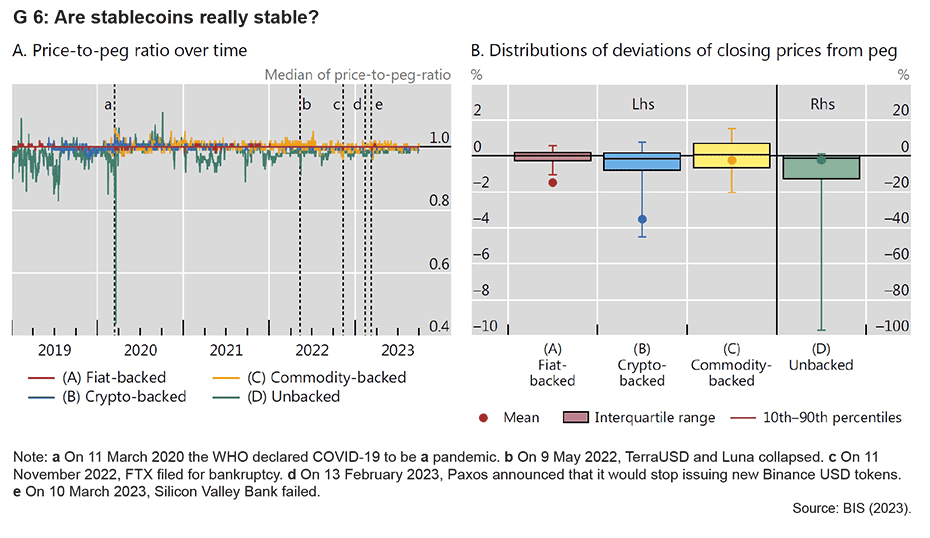

In many ways, stablecoins resemble traditional forms of banking or other investment vehicles such as money-market funds (MMFs). However, stablecoins remain largely unregulated and, in contrast to bank deposits and most MMFs, they cannot only be redeemed with the issuer but can also be traded in secondary markets. While stablecoins promise to maintain a stable value, chart G 6 shows that they have not always achieved this goal. For instance, when Silicon Valley Bank was collapsing in March 2023, USDC started to trade substantially below its peg – down to as low as 86 cents – since Circle, the company behind USDC, had a sizeable portion of its funds deposited at the bank.

In light of these observations, in external pageBuggenum, Gersbach and Zelzner (2023) we develop a theoretical model to address the question of how (fiat-backed) stablecoins should be designed and regulated so that they are both truly stable, i.e. always trade at their peg, and help to achieve efficient outcomes for the broader financial system and the economy overall. Drawing on the insights from this work, we make the following suggestions on how to regulate stablecoins. Since the external pageBasel Committee on Banking Supervision (2023) recently issued a public consultation on proposed amendments to its regulatory standards on cryptoassets, we discuss our suggestions in view of the Committee’s proposal.

Reserve asset quality and transparency

We agree with the Basel Committee that the assets used to back stablecoins should be of high quality, i.e. they should offer stable returns and low credit risk. As an extension of our own research indicates, stablecoins backed by assets with fluctuating returns would most likely be characterised by fluctuating pegs as well.

As far as the introduction of (stricter) disclosure and transparency requirements for stablecoin issuers’ balance sheets is concerned, paired with external audits to rule out window-dressing or outright fraud, we agree that such measures are much needed. They would merely match the long-standing regulations in banking, thereby helping to level the playing field between stablecoin issuers and traditional banks.

Reserve asset liquidity

The Basel Committee’s current proposal suggests that a stablecoin issuer’s reserve assets should be of short maturity and high liquidity in order to guarantee, at all times, the capacity to redeem all outstanding coins for the peg value. Under such regulation, stablecoin issuers would be similar in many ways to MMFs or would even resemble narrow banks in the event that they were also granted access to central bank reserves.

Our research yields a more nuanced view of the liquidity requirements for a stablecoin’s reserve assets – especially of its issuer’s willingness and obligation to liquidate assets to service all redemption requests at the peg even if the market value of reserve assets is below the peg. Such a situation can occur if, for example, treasury-bond yields increase suddenly. We argue that it is essential to consider the interaction between primary and secondary markets for stablecoins.

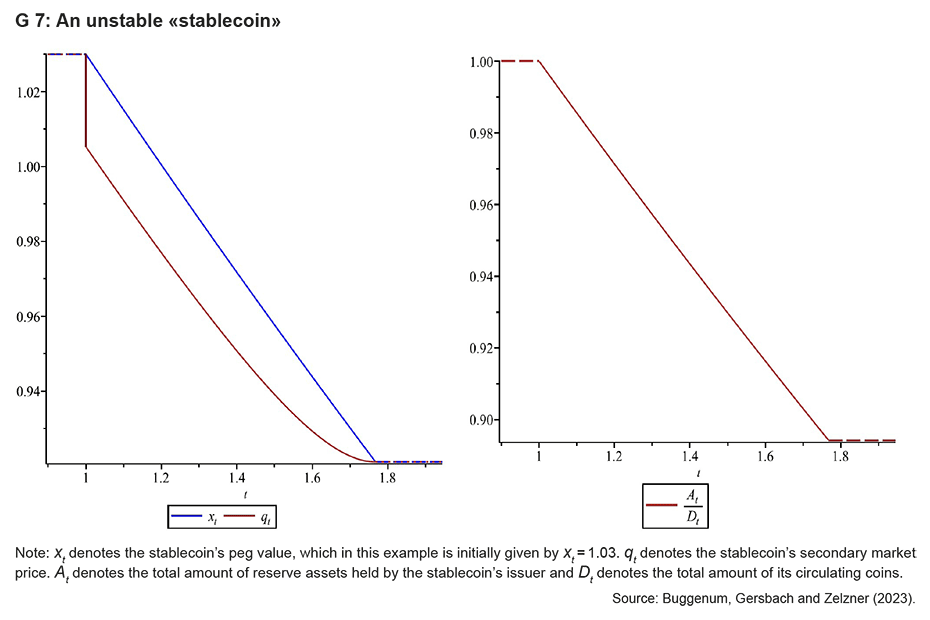

In particular, stablecoins that commit to service as many redemptions as possible in the primary market are especially prone to episodes of heightened secondary market volatility. This is because servicing (too) many redemptions in the primary market can lead to a situation where the amount of reserve assets contracts too fast relative to the stock of circulating stablecoins. This can cause a stablecoin to trade at a discount in the secondary market if market participants anticipate that a rapid decrease in reserve assets must entail a lower future peg. In turn, such a secondary market discount gives rise to a profitable carry-trade strategy where coins are bought at a discount in the secondary market and then sold to the issuer at the peg in the primary market, thus triggering excessive redemption requests.

Chart G 7 illustrates such a case. If the stablecoin’s secondary market price q_t suddenly and unexpectedly drops below its peg value x_t, this causes excessive redemption requests that result in a decrease in the issuer’s ratio of reserve assets A_t to circulating coins D_t. This, in turn, makes the stablecoin lose its initial peg and never regain it.

We find that issuers can stabilise the market, and thus avoid a situation as described above, by committing, perhaps counterintuitively, to limit the amount of redemptions they service, precisely because this prevents a sudden contraction in reserve assets. The presence of a well-functioning secondary market, in turn, ensures that individual market participants can always sell their stablecoins at the peg – if not in the primary market then in the secondary market. On this point we suggest that regulation should allow for redemption limits in times of distress – as is already the case for MMFs.

Our findings demonstrate the importance of studying the dynamics of primary and secondary stablecoin markets jointly. As pointed out in a recent policy note by the external pageFed Board of Governors (2024), understanding these joint dynamics requires further analysis. Statistical tests on stablecoin stability, as put forward by the Basel Committee, thus ideally take into account the total dynamics of the stablecoin market – not just the behaviour of secondary market prices in relation to pegs.

Interest on stablecoins and stablecoin competition

Although absent from the Basel Committee’s proposal, our research suggests that there is a rationale for regulating interest payments on stablecoins. As is also argued by others (e.g. external pageGorton and Zhang, 2021), one reason is that stablecoin issuers could compete funds away from the traditional banking system, potentially causing problems related to monetary policy, financial stability and credit intermediation. This could particularly become a problem if stablecoin issuers are allowed to hold central bank reserves, if the popularity of stablecoins continues to grow and if they are more widely adopted as a medium of exchange. Restricting interest payments on stablecoins could reduce these risks by easing competitive pressures on traditional banks, giving them time to adapt.

Our conceptual research further indicates that zero interest can be optimal if stablecoins are used by investors to provide insurance against liquidity demand shocks. Such a role for stablecoins is arguably relevant, given their widespread use for settlement in DeFi markets and to facilitate trades on cryptoexchanges.

Additionally, we find that interest-paying stablecoins can be contagious for other stablecoins, i.e. a single interest-bearing stablecoin may require other stablecoins to pay interest as well, or else they become unattractive and face runs. Unregulated stablecoin competition can thus give rise to coordination problems and multiple (undesirable) equilibria in which stablecoin returns fluctuate widely. This result has two main policy implications.

First, evaluating a stablecoin’s stability for regulatory purposes should be done in the context of the entire stablecoin market. In particular, although a single stablecoin may have been stable in the past, it can be subject to contagion from new stablecoins in the future. Statistical tests which assess a stablecoin’s stability should thus also account for a stablecoin’s vulnerability with respect to aggregate developments in the stablecoin market.

Second, regulation which hinders interest-bearing stablecoins or treats zero-interest coins favourably can serve multiple purposes. The creation of a competitive advantage for zero-interest stablecoins makes it less likely that such coins will be contaminated by interest-bearing coins, which promotes market stability. Further, in light of our finding that zero-interest coins provide optimal insurance against investors’ liquidity shocks, regulation on this matter can help stablecoin issuers to coordinate on the economically efficient equilibrium.

Concluding remarks

Overall, stricter regulation of the growing stablecoin market is vital to protect coin holders and limit the risks to the broader financial system. In our view, calls to ban stablecoins altogether seem exaggerated and would be difficult to implement in practice. A well-regulated stablecoin sector poses little threat and could foster innovation and competitive pricing within the traditional banking sector owing to pressure from outside. It could also spur new financial and technical innovation outside the traditional system, such as DeFi, which needs a stable means of on-blockchain settlement to attain its full potential.

References

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2023), Consultative Document: Cryptoasset standard amendments, issued for comment by 28 March 2024. external pagehttps://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d567.htm

BIS (2023), Authors: Kosse, A., Glowka, M., Mattei, I., and Rice, T., “Will the Real Stablecoin Please Stand Up?” BIS Papers No. 414. external pagehttps://www.bis.org/publ/bppdf/bispap141.htm

Buggenum, H., Gersbach, H., and Zelzner, S. (2023), “Contagious Stablecoins?”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 18521. external pagehttps://cepr.org/publications/dp18521

Fed Board of Governors (2024), Fed’s Note “Primary and Secondary Markets for Stablecoins.” external pagehttps://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/primary-and-secondary-markets-for-stablecoins-20240223.html

Gorton, G and Zhang, J. (2021), “Taming Wildcat Stablecoin,” University of Chicago Law Review 90. external pagehttps://lawreview.uchicago.edu/print-archive/taming-wildcat-stablecoins

Contacts

Makroökonomie, Gersbach

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

Makroökonomie, Gersbach

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

Makroökonomie, Gersbach

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland