The free movement of people has had no impact on the number of apprenticeships

Has the free movement of people had a negative impact on Swiss firms’ willingness to train apprentices? A new study shows that the number of apprenticeships did not fall during the first few years following the opening of the country’s border. However, the reasons why firms train apprentices has changed because it has become easier and cheaper for them to recruit suitable workers externally.

Does firms’ willingness to train apprentices depend on how easy it is for them to recruit skilled workers in the external labour market? This is theoretically conceivable, and the empirical literature on why firms train apprentices also points to a potential trade-off between the supply of skilled workers in the external labour market and firms’ willingness to offer training. This conflict of objectives is sometimes referred to as a ‘make-or-buy’ decision.

Against this backdrop it is not surprising that politicians and observers of the Swiss labour market expressed fears that the free movement of people could come at the expense of apprenticeship training at Swiss firms. This ultimately led to the complete opening of the labour market to citizens from the EU/EFTA area who, from then on, had full access to the Swiss labour market. This massively increased the numbers of highly skilled external workers that Swiss firms could access without any restrictions.

In a study recently published in the scientific journal Labour Economics, Maria Esther Egg-Oswald (ETH Zurich) and KOF labour market expert Michael Siegenthaler examine the impact that the free movement of people had on apprenticeship training in Switzerland during the first few years after it came into force.

Firms close to the border more affected by the free movement of people

To answer this question, the two researchers draw on the fact that the local supply of skilled labour for firms located near the border has grown more strongly than that for businesses located further away. This is because the free movement of people lifted the previous restrictions on the employment of cross-border commuters from Switzerland’s neighbouring countries. As Siegenthaler was able to show in an earlier study together with three co-authors (see Beerli, Ruffner, Siegenthaler, Peri 2021), this led to firms in the immediate vicinity of the border hiring significantly more EU workers after 2000 than businesses far away from the border. A large proportion of these newly hired EU workers were highly skilled.

Based on the previous study, Oswald-Egg and Siegenthaler therefore use the ‘difference-in-differences’ (DiD) method to analyse the effects that the free movement of people has on apprenticeship training. The authors investigate whether the numbers of apprenticeships at firms located close to the border differed over time from those at firms further away from the border. Für ihre Analysen verwenden Oswald-Egg and Siegenthaler use two data sets for their analysis. Firstly, they utilise the Swiss business censuses from 1995 to 2008, which show the numbers of apprentices and the employment of foreign workers at all firms across Switzerland during the survey years.

Secondly, they draw on extremely diverse data on the costs and benefits of apprenticeship training in Switzerland. These surveys asked a sample of around 11,000 firms about the costs and benefits of apprenticeship training in 2000, 2004 and 2009. The costs of recruiting external skilled labour are also recorded in detail in these surveys.

Firms close to the border train fewer apprentices

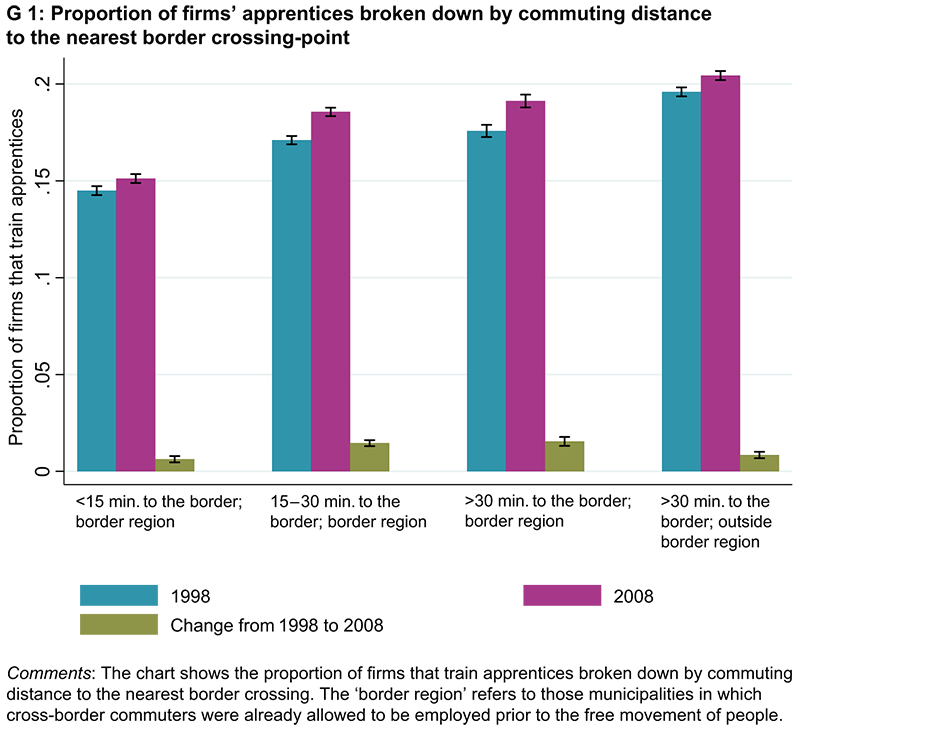

Before analysing the effects of the free movement of people, the authors use business census data to investigate whether the propensity to offer training is related to proximity to the border. This data enables each company to be precisely located geographically using geo-coordinates. The data shows a fairly strong correlation between apprenticeship training and proximity to the border: firms close to the border are around 5 percentage points or 25 per cent less likely to train apprentices than businesses that are further away from the border (see chart G1).

The number of apprentices is also much lower at firms located close to the border. Conversely, businesses close to the border employ significantly more cross-border commuters. Does this mean that cross-border commuters are replacing apprentices?

The free movement of people did not reduce the number of apprenticeships

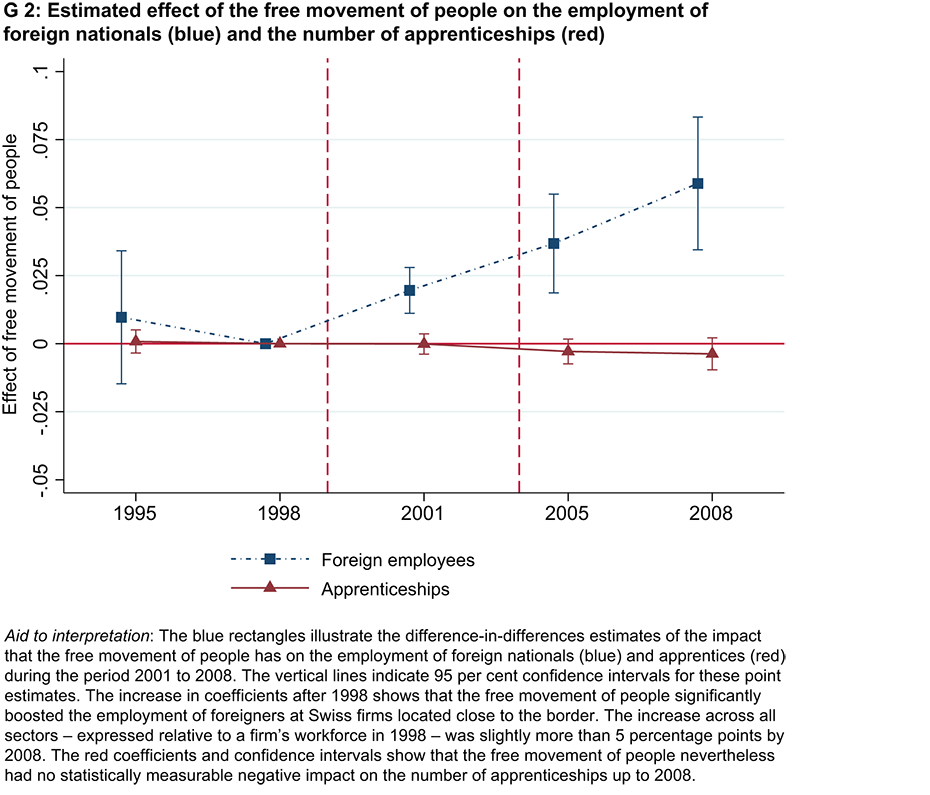

The answer to this question is provided by causal estimates using the DiD method and it is ‘no’: cross-border commuters and the provision of apprenticeships were not substitutes – or at least not in the first few years after the free movement of people came into force. This peer-reviewed study shows – analogous to the earlier study – that firms located close to the border employed significantly more additional foreign nationals than businesses further away from the border. This also applies to firms that train apprentices. Nevertheless, the numbers of apprenticeships at firms located near to and far from the border were similar over time (see chart G2).

The probability of training apprentices at all was roughly the same in both regions over time. Both observations suggest that the opening of the border had no impact on the numbers of apprenticeships, even at heavily affected firms located within just a few minutes’ drive of the border. These findings also suggest that the correlation in chart 1 is not necessarily causal: firms close to the border may not be training fewer apprentices than firms within Switzerland because of cross-border commuters. There may also be a third factor behind the negative correlation.

In further analysis the published study examines the question of why the free movement of people had no measurable impact on apprenticeship training. It shows that this was due to two opposing effects that cancelled each other out on average: a cost effect and a scale effect.

The free movement of people changed the motives for training

The cost effect can be seen from the fact that the free movement of people has made it easier and cheaper for firms to hire skilled workers in the external labour market. In the cost-benefit data this is reflected in the fact that the free movement of people has made it easier for firms to find labour that meets their specific requirements.

The free movement of people also reduced the likelihood of a firm reporting difficulties in recruiting sufficient local skilled labour in the survey. The result was a significant reduction in the cost of hiring skilled workers. Oswald-Egg and Siegenthaler estimate that the opening of the border reduced the time it took for newly hired employees to achieve full productivity by 12 per cent. Newly recruited skilled workers became 11 per cent more productive during this adjustment period.

As one would expect based on make-or-buy considerations, this fall in costs had an impact on firms’ motives for training. The free movement of people meant that there were fewer firms close to the border stating in the survey that they were training apprentices in order to reduce the cost of external recruitment or because it was difficult to find workers in the external labour market.

Firms close to the border grew disproportionately

Why – despite this change in training motives – was there no decline in the number of apprenticeships near the border? According to the new study, which is consistent with similar findings in the earlier study, the free movement of people had a significant, positive effect on the size of firms, particularly in the manufacturing and private service sectors. In other words, firms located close to the border grew disproportionately thanks to their highly skilled foreign workforces.

Despite a decline in the proportion of apprentices in employment, there was no decrease in the number of apprentices. The exception in this respect was the construction sector, where the free movement of people had no measurable positive impact on the size of firms. Accordingly, Oswald-Egg and Siegenthaler find some evidence that the opening of borders in the construction sector slightly reduced the number of apprenticeships.

References

Oswald-Egg, M. E. & M. Siegenthaler (2023): Train drain? The availability of foreign workers and firmsʼ willingness to train, Labour Economics, 85(12), 10243.

Beerli, A., J. Ruffner, M. Siegenthaler, & G. Peri (2021): The abolition of immigration restrictions and the performance of firms and workers: evidence from Switzerland. American Economic Review, 111(3), 976–1012.

Contact

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland