Between market power and labour rights: the impact of the seasonal worker statute on immigrants’ wages

Switzerland’s seasonal worker statute, which was abolished in 2002, tied residence permits to employers. According to the monopsony theory, such regulation gives employers greater bargaining power in wage-setting and could depress wages. This article analyses this hypothesis and suggests that immigrants’ social and economic rights – strengthened by the free movement of people – may have helped to reduce wage differentials.

Temporary work visas have a long tradition in many countries as a means of dealing with labour shortages. For decades, Switzerland also had a well-established system of recruiting labour in specific sectors and regions that were unable to meet their needs domestically over certain periods of time. While the exact nature of such regulation differs from country to country and depends on the period concerned, two aspects are common to almost all guest worker programmes: the residence permit is limited in time and it is tied to a specific job. The latter means that changing employer is more difficult and is often associated with the risk of losing the residence permit. This institutional restriction on labour market mobility weakens workers’ bargaining position and gives firms market power. In labour market research this phenomenon is referred to as monopsony power. In the context of guest worker programmes it is argued that such power weakens the bargaining position of workers and can therefore encourage discrimination and wage dumping (Norlander, 2021).

This criticism is not new. Human rights organisations, left-wing parties and trade unions, as well as (former) employees operating under the seasonal worker status themselves, have long criticised guest worker programmes because of their challenging conditions (Mahnig & Piguet, 2003). The seasonal worker statute in Switzerland was abolished in 2002 with the introduction of the free movement of people – partly in response to this criticism. However, guest worker programmes continue to exist in countries such as Spain, where Moroccan mothers are specifically recruited as harvest workers (Glass et al., 2014). In Switzerland, too, calls for the reintroduction of the seasonal worker status are regularly heard, although they have not yet been widely discussed.1

This article analyses the effects of Switzerland’s seasonal worker status on the wages of seasonal workers. The labour market mobility of seasonal workers was severely restricted under the quota system, which limited their bargaining power vis-à-vis employers. The introduction of the free movement of people and the right to geographical and occupational mobility has shifted the balance of power in favour of employees. According to the monopsony theory, the wages of seasonally or temporarily employed migrants are therefore expected to have risen since 2002. This analysis tests this hypothesis. It examines how the wages of workers with seasonal permits (short-term residence permits after 2002) changed over time in comparison with the wages of workers with Swiss passports before and after the introduction of the free movement of people. This analysis is based on the Swiss Salary Structure Survey (SSSS), a representative poll of wages at Swiss firms conducted by the Federal Statistical Office (FSO).

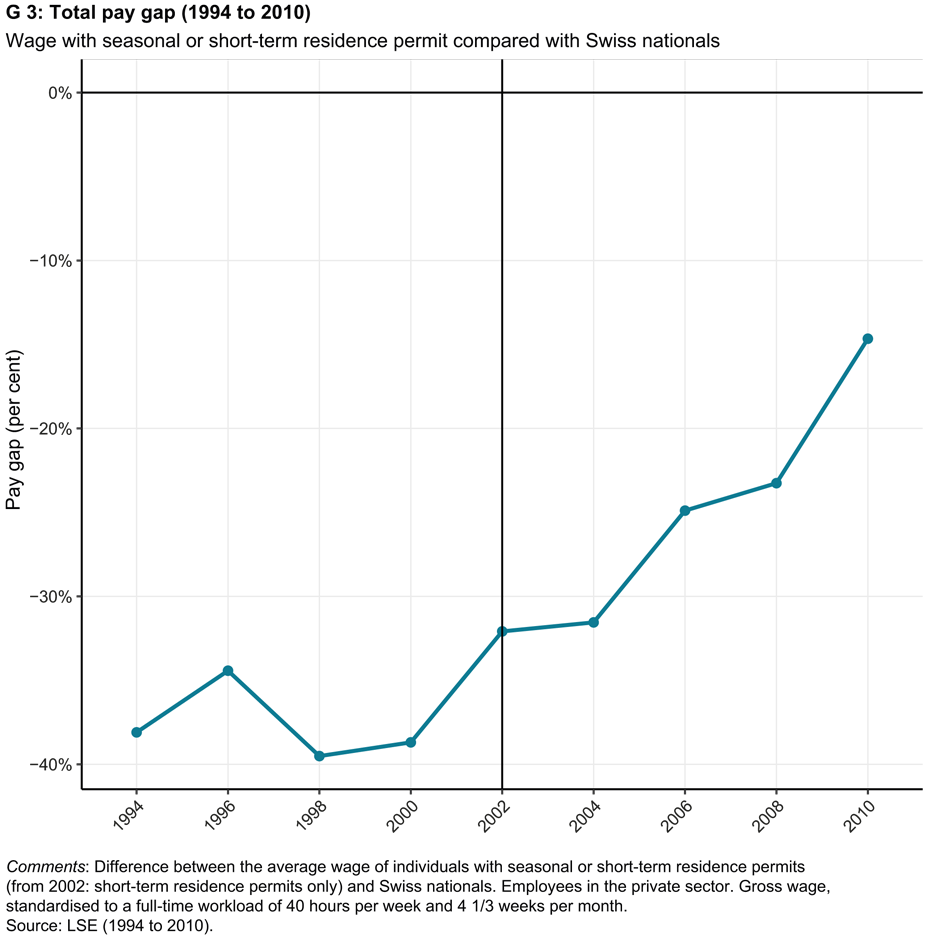

Chart G 3 first shows that the wages of seasonal workers were over a third lower than those of workers with Swiss passports in the mid-1990s. After the free movement of people was introduced, wage differentials between individuals on short-term residence permits – which largely replaced seasonal permits – and workers with Swiss passports fell continuously. However, the free movement of people has also changed the composition of the immigrant labour force2. Compared with the previous seasonal workers, workers on short-term residence permits are, on average, better educated and work less frequently in the typical seasonal sectors of construction and catering and more frequently in other, often better-paid sectors. The following analysis considers these and other factors, which experience has shown to be relevant for wage-setting, as control variables. The key question is whether changes in the composition of immigration can explain the decline in wage differentials over time. If this is not the case, this can be seen as an indication that the migrants’ rights strengthened as part of the free movement of people have enabled them to successfully demand higher wages.

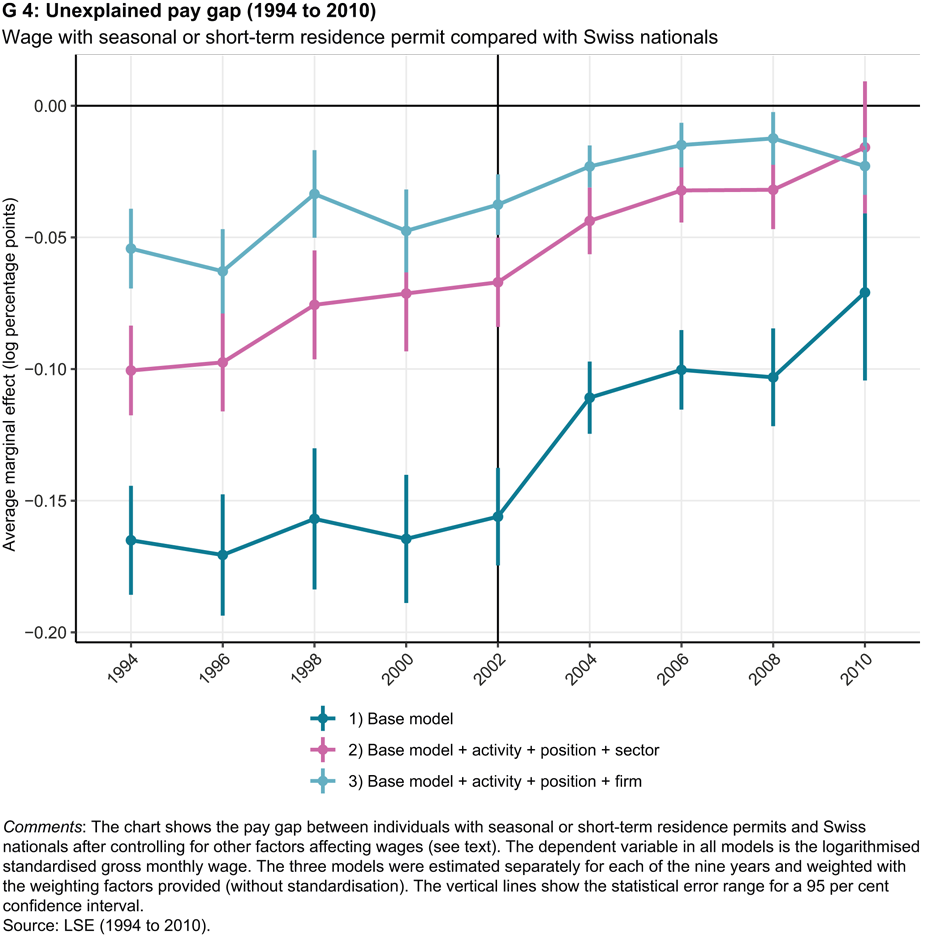

Chart G 4 shows the estimated impact of residence status on wages under three regression models. In model 1, human-capital variables, demographic variables and the region are considered as control variables. Specifically, these are the highest educational qualification, potential experience3, length of service, gender, marital status and labour market region4. The resulting coefficient for seasonal workers in 1996 shows that, if these factors are held statistically constant, there is still an unexplained pay gap of 17 per cent compared with Swiss workers. No change in the pay gap is visible immediately after the introduction of the free movement of people (October 2002). It is expected that any effect of the adjusted residence permits would not manifest itself at least until the seasonal permits issued in spring 2002 and valid until the end of 2002 have expired. The wage gap will fall sharply to between 7 and 10 per cent over the following years.

In Model 2, the occupation, professional position and the employer’s sector are also taken into account as control variables. Since seasonal workers were often employed in low-wage occupations and sectors, the wage differential prior to 2002 drops to between 7 and 10 per cent. Although workers on short-term residence permits were increasingly employed in better-paid occupations and sectors after 2002, however, the decrease in the wage gap compared with Model 1 remains almost the same. This suggests that changes in the composition of occupations and sectors can only explain a small part of this decline.

Model 3 considers each individual firm as a control variable instead of the sector and labour market region. This means that only the wages of employees of the same firm who are similar in the controlled dimensions are compared. It is interesting to note that controlling for the firm in Model 3 further reduces wage differentials prior to 2002. This could be interpreted as meaning that seasonal workers within these sectors were more likely to work at low-paying firms while Swiss workers were more likely to work at high-paying firms. However, this no longer seems to be the case after 2002. This would mean that newly arrived short-term residents not only increasingly worked in other sectors and better-paid positions but also found their way into better-paying firms.

Overall, this analysis shows that the unexplained pay gap between workers on short-term residence permits and those with Swiss passports is significantly smaller after 2002 than the wage gap between workers on seasonal permits and those with Swiss passports was previously. These findings indicate that these migrants’ wages were too low in relation to their labour productivity and that the strengthening of their rights after the introduction of the free movement of people has helped to reduce the pay gap. The findings are consistent with recent studies on guest worker programmes, which show that tying residence status to employers poses the risk of undercutting wages.

------------------------

1The Swiss People’s Party (SVP) called for the reintroduction of the seasonal worker status as part of its popular initiative entitled ‘Against Mass Immigration’ (Mariani, 2014). This demand was recently repeated in connection with the widespread labour shortage (Hohler, 2023).

2Further figures and charts on the changing composition of immigration can be found in the long version of this article.

3Potential experience is calculated as the age minus the number of years of education minus five years.

4Potential experience and length of service are included in the quadratic term. Gender and marital status are also factored in.

References

Glass, C. M., S. Mannon, & P. Petrzelka (2014): Good mothers as guest workers. International Journal of Sociology, 44(3), 8–22.

Hohler, D. (2023): Hotelier fordert die Rückkehr der Saisonniers. Der Bund. external pagehttps://www.derbund.ch/berner-hotelier-fordert-rueckkehr-der-saisonniers-402715550118

Mahnig, H. & E. Piguet (2003): Die Immigrationspolitik der Schweiz von 1948 bis 1998. In H.-R. Wicker, R. Fibbi, & W. Haug (Hrsg.), Migration und die Schweiz. Ergebnisse des Nationalen Forschungsprogramms «Migration und interkulturelle Beziehungen» (S. 65–108). Seismo Verlag.

Mariani, D. (2014): Die Auferstehung des Saisonnier-Statuts. swissinfo.ch. external pagehttps://www.swissinfo.ch/ger/wirtschaft/arbeitsbewilligungen_die-auferstehung-des-saisonnier-statuts/37748944

Norlander, P. (2021): Do guest worker programs give firms too much power? IZA World of Labor, 484.

Contact

KOF FB Arbeitsmarktökonomie

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland