The weakness of the global economy persists

Restrictive monetary policy, falling but still high inflation and multiple uncertainties will continue to slow the global economy this year. According to the KOF Economic Forecast, worldwide business activity will not pick up again until 2025.

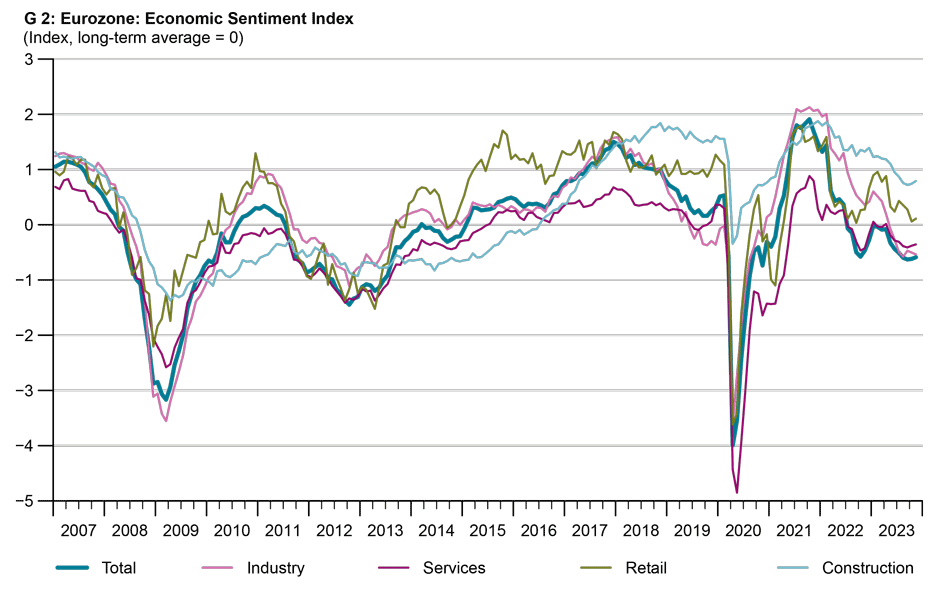

Global economic activity has been subdued since 2022 and, as expected, worldwide output growth remained below average in the third quarter of 2023. High inflation is limiting purchasing power and monetary policy is having a constraining effect. A large degree of political and economic uncertainty is increasingly restraining consumption and investment. The global economy is likely to remain weak in last quarter of 2023, as suggested by sentiment indicators for the eurozone, for example.

A gradual but less pronounced recovery should then begin this year. As expected, global inflation has continued to fall after it peaked at the end of 2022. However, it is likely to be some time before inflation in the eurozone and the US returns to around 2 per cent. Accordingly, KOF – in contrast to some financial market players – expects to see hardly any interest-rate cuts this year.

Global output has expanded below average since 2022

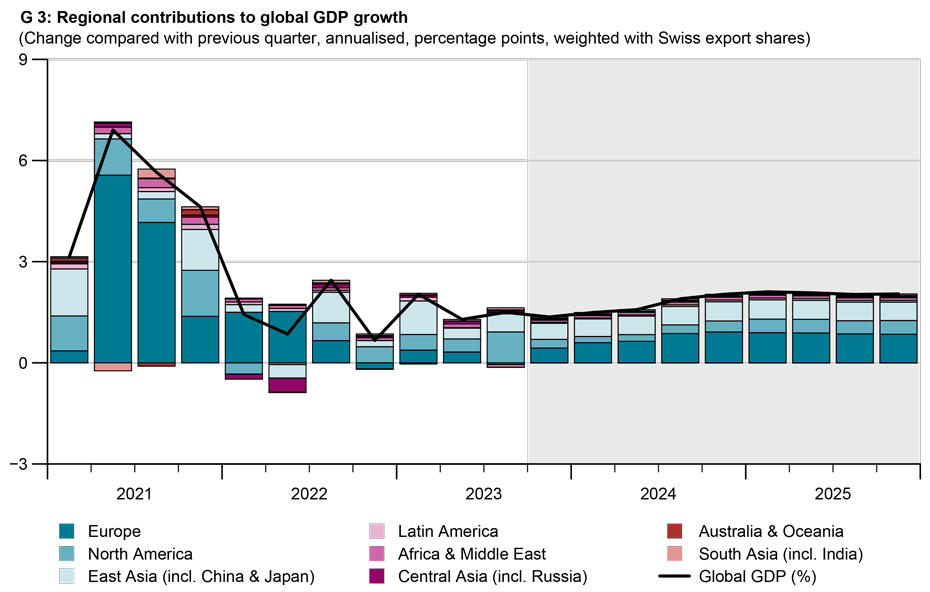

Pent-up demand after the COVID-19 crisis caused a sharp rise in global output in 2021. However, supply shortages and supply chain problems limited expansion in the first half of 2022 and were compounded by massive energy price hikes and supply disruption in the wake of the war in Ukraine. While restrictions on the supply side gradually became less important, obstacles increasingly emerged on the demand side. For example, the surge in inflation that began in 2021 reduced the purchasing power of households, limiting private consumption.

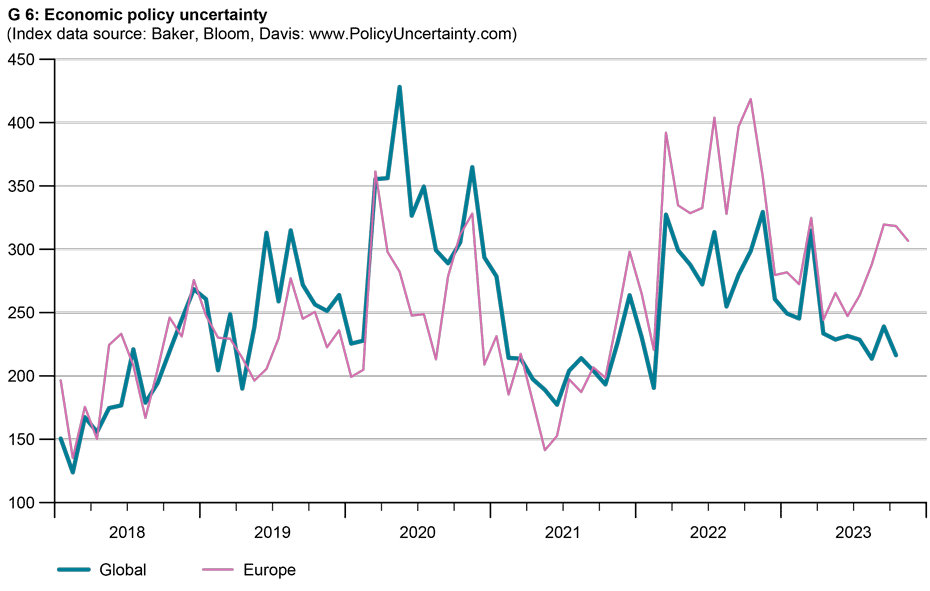

In addition, monetary policy is currently restrictive and is therefore dampening the propensity to invest. The high level of uncertainty now is another important constraining factor (more on this below). Consequently, global output weighted with Swiss export shares recorded below-average annualised growth of 1.5 per cent in the third quarter of 2023 (average annualised growth rate over the past ten years: 2 per cent).

US GDP stronger than expected in the third quarter; German GDP contracted as expected

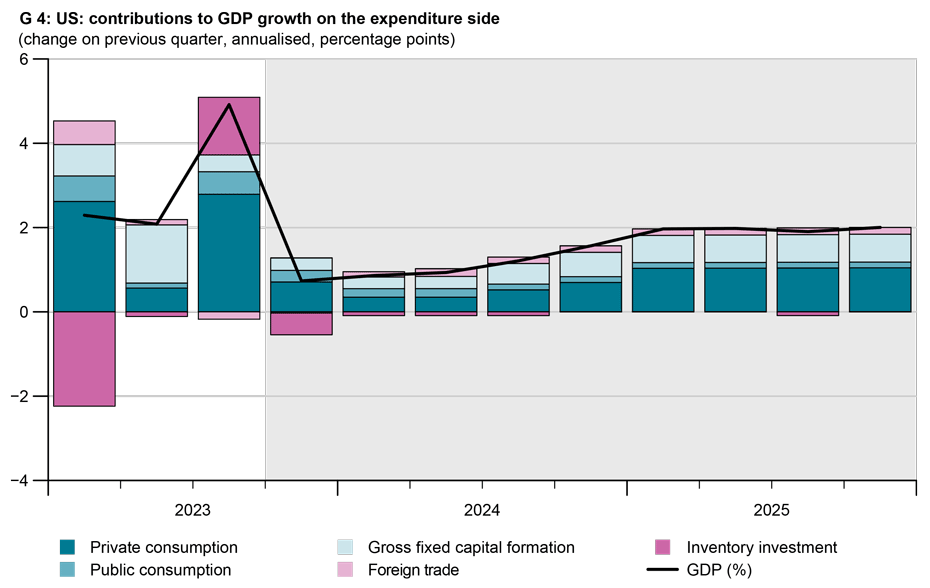

Eurozone gross domestic product (GDP) contracted by an annualised 0.2 per cent in the third quarter of 2023. Germany in particular dragged the aggregate down by 0.5 per cent owing to a decline in consumption, while French GDP increased by 0.4 per cent thanks to solid domestic demand, and Italian GDP at least rose slightly (by 0.2 per cent). US GDP rose more sharply than expected (4.9 per cent), driven by a strong contribution from inventories and high consumption growth. In addition to the consistently encouraging labour market situation, a continued reduction in excess savings is likely to be responsible for the strong consumer momentum – in stark contrast to Germany, for example, where cautious saving prevails. Chinese GDP also rose surprisingly sharply in the third quarter (by 5.3 per cent) despite relatively weak indicators. By contrast, Japan’s GDP contracted by 2.1 per cent in the third quarter following a significant increase in the first half of 2023.

Decline in energy price contribution mainly responsible for fall in inflation

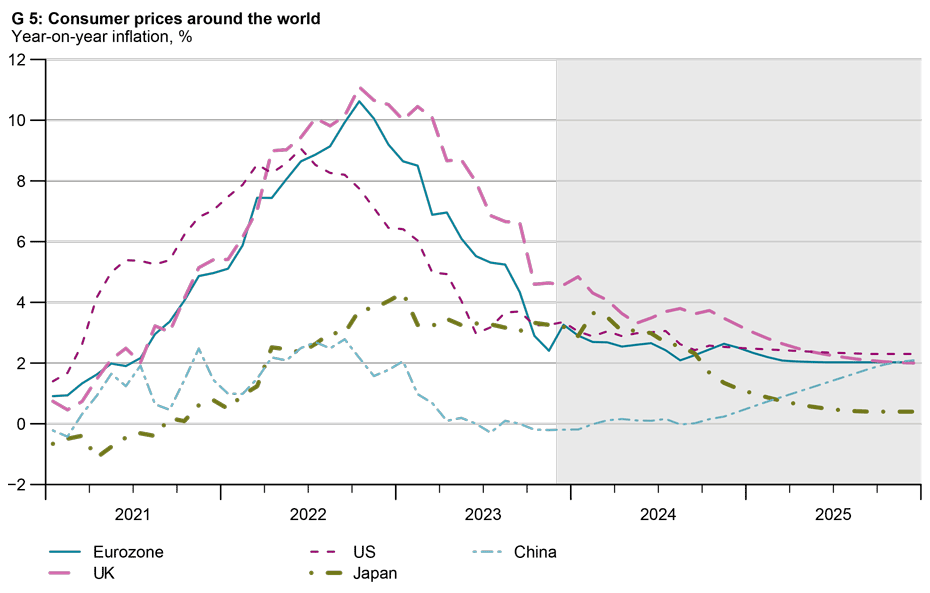

After consumer price inflation had reached historic highs in many places in 2022 and early 2023 (eurozone: 10.6 per cent in October 2022, United States: 9.1 per cent in June 2022, United Kingdom: 11.1 per cent in October 2022, Japan: 4.3 per cent in January 2023), inflation continued to trend downwards almost everywhere until recently. In November 2023, inflation in the eurozone was only 2.4 per cent, in the US it was 3.2 per cent in October, in the UK it was 4.6 per cent and in Japan it was 3.3 per cent. The main reason for the fall in inflation over the course of 2023 is the declining contribution of the energy price component to overall inflation.

Core inflation – i.e. inflation excluding the volatile prices of energy and food, which generally determine monetary policy – has also fallen in the eurozone, the US and the UK in recent months, although it remains well above target (eurozone: 4.2 per cent in November, US: 4.0 per cent in October, UK: 6.3 per cent in October). Core inflation in Japan rose significantly over the course of the year and stood at 2.7 per cent in October. The last time it was this high was in the early 1990s. Inflation performed quite differently in China, which is currently being affected by a property crisis. Given its sluggish economy, the rates of change in both the core and overall price indices have been close to zero since the spring of 2023.

Restrictive monetary policy

The world’s major central banks have recently refrained from further interest-rate hikes in view of falling inflation and weak or weakening economic activity in many places. The most recent increase in the main refinancing rate of the European Central Bank (ECB) dates back to 23 September last year (up 25 basis points to 4.75 per cent), the latest rise in the federal funds rate of the US Federal Reserve (Fed) was on 26 July (up 25 basis points to a target range of between 5.25 per cent and 5.50 per cent), and the Bank of England’s bank rate was last hiked on 3 August (up 25 basis points to 5.25 per cent). As a consequence of past interest-rate rises, monetary policy is clearly restrictive in many places, meaning that real interest rates are higher than natural rates. This is despite the fact that inflation forecasts are currently higher than they were in the past, which in itself lowers real interest rates.

The Japanese central bank is taking a completely different approach from the aforementioned central banks. So far it has stuck to its ultra-expansionary monetary policy, making only a few tweaks. Given that its economic policy has long been geared towards reflation, the rise in inflation in Japan should be seen as a success even if the central bank emphasises that this is not yet sustainable. Because the Chinese economy is weak, the country’s central bank is pursuing an expansionary course by cutting interest rates and injecting more liquidity.

Multiple uncertainties will continue to dampen the global economy this year

Various uncertainties will dampen global economic activity during this quarter and the last one. Given the uncertain inflation outlook and subdued sentiment, European households in particular are currently tending to save cautiously. Accordingly, consumer spending is likely to remain weak for the time being. The high level of geopolitical uncertainty is depressing investment sentiment. There is also economic policy uncertainty in some countries – such as the recurring risk of a government shutdown in the US.

In addition, restrictive monetary policy is another key factor behind the weak investment momentum in many countries. Fiscal stimulus, which fuelled the recovery after the coronavirus pandemic, is also currently absent. The allocation and spending of funds from the EU Recovery and Resilience Facility, from which Italy in particular is benefiting, is taking longer and happening more slowly than previously expected. One fiscal policy exception is currently China, which decided to launch a debt-financed infrastructure programme in October in response to poor economic indicators and allowed local governments to fast-track the raising of new loans or the rolling-over of existing ones. This should stimulate GDP growth in China in the short term, creating slightly positive knock-on effects for the global economy (relative to a situation in which the Chinese economy goes into a tailspin again).

Although an economic recovery is expected in the second half of 2024, the conditions required for a strong upturn are currently absent. KOF expects global GDP weighted with Swiss exports to increase by 1.5 per cent for 2023 as a whole (autumn forecast: 1.4 per cent). Its forecasts for 2024 and 2025 are 1.6 per cent and 2.0 per cent respectively. This represents a downward revision compared with its autumn forecast (1.9 per cent and 2.2 per cent respectively). Its GDP forecasts for the eurozone for 2023 to 2025 are 0.5 per cent, 0.9 per cent and 1.5 per cent respectively. KOF is forecasting 2.4 per cent, 1.6 per cent and 1.7 per cent respectively for the United States.

Core inflation will fall this year

This subdued economic activity is likely to cause a further decline in core inflation in the eurozone, the US and other countries during the forecasting period. However, KOF expects this decline to be slow. Inflation in key eurozone countries, the US and the UK is likely to remain above target at the end of 2024. One reason for this is that the continuing solid labour market situation in many places together with high wage demands (to compensate for past real wage losses) will continue to drive wage momentum this year.

Wage increases will partially feed through into consumer prices owing to the below-average but not yet critical level of economic growth. KOF is forecasting eurozone inflation of 5.5 per cent for 2023, 2.5 per cent for 2024 and 2.1 per cent for 2025, while inflation in the US is expected to reach 4.1 per cent in 2023, 2.8 per cent in 2024 and 2.4 per cent in 2025. Given these forecasts, KOF sees no reason for the ECB and the Fed to cut interest rates before mid-2024.

Short-term risks due to energy price trends; medium-term risks due to high debt levels

This forecast is based on the technical assumption that energy prices will remain constant in real terms in 2024 and 2025. One forecasting risk is that energy prices could rise significantly – for example as a result of any further escalation of the conflicts in the Middle East and between the US/EU and Russia – causing inflation to bounce back and impacting the real economy. Conversely, a fall in energy prices could prompt central banks to cut interest rates prematurely, which – all other things being equal – would stimulate economic growth. Past interest-rate hikes in some places have put pressure on property prices, which had previously risen sharply in some cases. There is a risk of local property crises that could escalate into a global crisis via the international financial markets.

The property crisis in China is has had only a mild impact on the global economy because China has opened its financial markets to foreign banks to only a limited extent. The high levels of public debt in many countries pose a medium-term downside risk. Given the gradually increasing interest burden on the public finances, this does not appear to be sustainable for some countries in the long term.

Contacts

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

KOF FB Konjunktur

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

KOF FB Konjunktur

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland