The mental health of the Swiss population during the pandemic

How did the Swiss fare during the first two waves of the COVID-19 pandemic? Using data from Dargebotene Hand and Swisscom, analysis conducted by Marc Anderes and Stefan Pichler shows that calls to the Dargebotene Hand helpline increased significantly just after the outbreak of the pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic required drastic measures to be imposed to reduce infection rates. These included social distancing and a general reduction in mobility, which temporarily caused a marked decline in economic activity. In addition to economic considerations, however, it is important to understand the wider consequences of the pandemic and the associated social costs. How did the Swiss population fare after the outbreak of the pandemic? If there were any negative consequences, was this change temporary or long-term?

How do you measure the mental health of a population?

The health status of a population is difficult to measure. One common method is to conduct surveys, but this is often only possible at lengthy intervals owing to the effort involved. New approaches to measuring public well-being include the evaluation of online behaviour, e.g. the number of search queries relating to grief or anxiety, and analysis of telephone data. One advantage of these methods over traditional approaches is that the data is available on a daily basis and can be analysed in real time. This can be a benefit during a pandemic as it enables timely policy management, for example.

Analysis conducted by economists Marc Anderes and Stefan Pichler uses machine-recorded call data from Switzerland’s nationwide Dargebotene Hand (DH) counselling service to examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. DH offers a free telephone counselling service around the clock in all regions of Switzerland. Its database contains not only the total number of calls (including unanswered calls) but also an anonymised identification number for each caller.1

Significant increase in people seeking help after the outbreak of the first wave

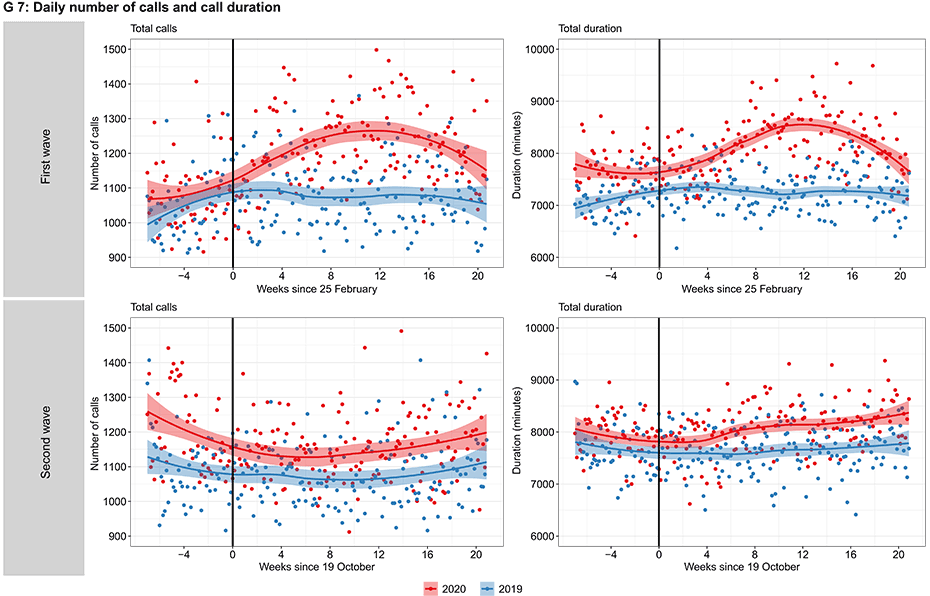

Firstly, the authors compare the number of calls and the total call duration after the outbreak of the pandemic with previous periods. Chart G7 shows the daily number of calls (‘Total calls’, left) and the daily call duration in minutes (‘Total duration’, right) for the years 2019 (blue) and 2020 (red) during the first wave (‘First wave’, top) and the second wave (‘Second wave’, bottom). The black vertical line indicates the start of the first wave (25 February 2020) and the second wave (19 October 2020) respectively. The chart shows that calls and the call duration rose sharply after the outbreak of the first wave. In contrast, there was no such increase during the previous year. However, the effects are temporary, as the call volume normalises to the previous year’s level after around four or five months. Interestingly, the second wave, which started in the autumn of 2020, had little impact on Dargebotene Hand. The reasons for this are likely to be the less stringent measures introduced as well as familiarisation effects on the part of the population.

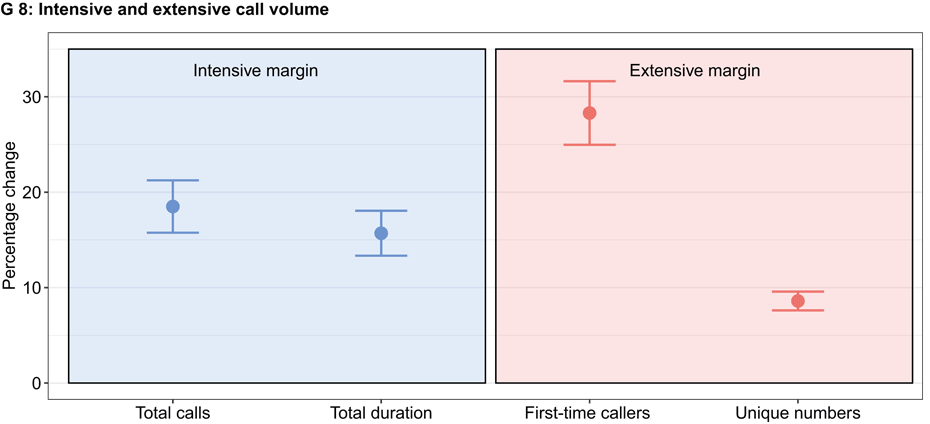

But what is causing the increase in calls? Do more people need help over the phone (‘extensive margin’), or do people who were already calling before the pandemic need more help than before (‘intensive margin’)? Chart G8 compares the 20 weeks after the outbreak of the first wave with the period before the pandemic and shows that both are true. Of those individuals who had already called before COVID, their total number of calls increased by 19 per cent and their call duration grew by 16 per cent. However, the number of callers also rose by 9 per cent, as can be seen in the right-hand panel of chart 4. A major reason for this increase is first-time callers (up by 28 per cent), which underlines the importance of counselling centres as widely accessible providers of mental health services.

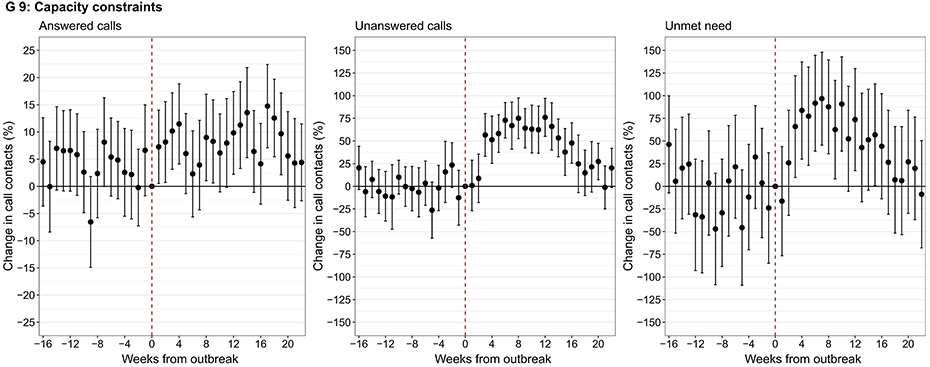

Finally, the authors analyse the extent to which the higher demand from the population caused capacity constraints on the helpline. They also isolate attempted calls that were not answered by the helpline within 24 hours in order to calculate a measure of the unmet need for help. Chart G9 presents regression coefficients with 95 per cent confidence intervals that show a comparison between the current week and the last week before the outbreak of the pandemic. If a coefficient is 5 per cent, for example, the call volume in that week is 5 per cent higher than it was in the week before the first registered COVID-19 case (25 February 2020). The results show that the Swiss helpline was struggling with severe capacity constraints. Twelve weeks after the outbreak of the pandemic the number of unanswered calls was 75 per cent higher than it had been in the initial week (middle chart). If the number of unanswered calls is subtracted from the total number of calls, there is only a modest increase in the number of answered calls (chart on the left). The authors also note that capacity constraints cause a rise in unmet demand (chart on the right), which almost doubles after seven weeks. However, these trends are temporary.

Conclusion

This analysis shows that the public’s demand for psychological help after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic increased significantly, which caused capacity constraints and unanswered attempted calls. This trend was driven both by people who had previously called DH and also by a large number of new callers, which underlines the social relevance of the hotline. The growth in call volume was limited to the first wave, which is probably due to familiarisation effects on the part of the population and the absence of any lockdown during the second wave.

------------------------------------

1The data does not contain any call content and does not enable individual callers to be identified.

The article entitled external page‘Mental health effects of social distancing in Switzerland’ by Marc Anderes and Stefan Pichler

Contacts

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland