Falling wealth taxes contributing to rising wealth concentration

As in many other countries, wealth concentration in Switzerland has increased in recent decades and remains high. At the same time, taxes have regularly been reduced over the last 50 years. Wealth tax cuts explain around a quarter of the observed growth in wealth concentration. This means that there are other key drivers of wealth inequality besides taxes.

Those in favour of wealth taxes argue that a more progressive tax system would not only be fairer but would also help to slow the increase in wealth concentration that has been observed in many countries since the 1980s and 1990s. Wealth taxes have therefore gained popularity in the United States in particular in recent years. US presidential candidates Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren have even made the introduction of a wealth tax a key campaign issue.

According to the World Inequality Database, the richest 1 per cent of the population in the US owned 35 per cent of total wealth in 2019 compared with 22 per cent in 1978. external pageAnalysis by the PEW Research Center (2020) reveals that the richest 5 per cent are the only group to have increased their wealth since the Great Recession of 2007–2008. At the same time, the tax burden at the upper end of the distribution has decreased as taxes have been cut several times and tax loopholes have not been adequately plugged (Saez and Zucman, 2019).

Analysing wealth taxes: Switzerland constitutes a kind of laboratory

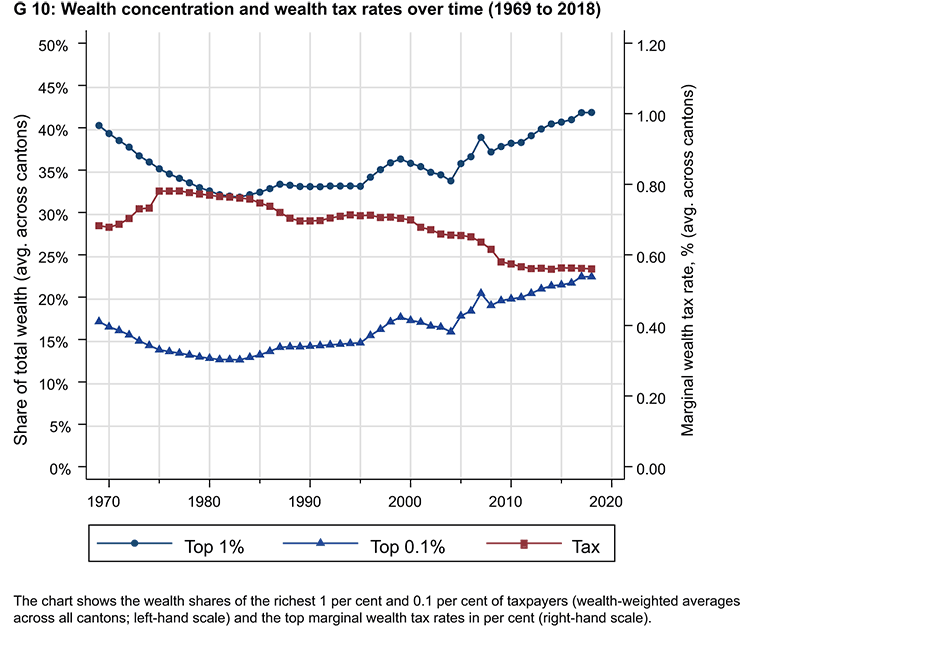

Wealth concentration in Switzerland has increased in recent decades and is among the highest in the world. At the same time, the tax burden on wealth and high incomes in Switzerland has decreased over the last 50 years (chart G10). However, systematic evidence of how (progressive) wealth taxes actually affect wealth concentration has so far been lacking.

In a new study entitled ‘Does A Progressive Wealth Tax Reduce Top Wealth Inequality? Evidence from Switzerland’, KOF economist Isabel Z. Martínez, Samira Marti, and Florian Scheuer from the University of Zurich examine this question by exploiting the decentralised structure of Switzerland’s wealth tax. As each of the 26 cantons sets its own wealth tax rates and adjusts them repeatedly over time, Switzerland represents a kind of laboratory in which wealth tax is constantly being experimented with.

History and diversity of wealth taxes in Switzerland

Wealth taxes in Switzerland have a long tradition that goes back much further than modern-day income tax. The Swiss cantons have been taxing wealth since the early 18th century. This was, in fact, their main source of income until the First World War. In addition, wealth was taxed at the federal level between 1915 and 1959.

Since then there has no longer been a nationwide wealth tax, although all cantons must levy a comprehensive wealth tax, which they are largely free to organise. The tax base is very broad: in principle, all assets – including assets held abroad – are subject to tax. Only joint household items, foreign property and private pension assets are exempt from wealth tax.

From an international perspective, Switzerland is now an exception in terms of wealth taxation. While twelve European countries levied an annual tax on net wealth in the 1990s, only three countries – Norway, Spain and Switzerland – still levy such a tax today.

With wealth tax revenue of 3.8 per cent of total state income, Switzerland is the only country with significant tax revenue comparable to the proposals being discussed to introduce a wealth tax in the United States. The example of Switzerland is therefore particularly interesting for the ongoing political debate in the US and other countries.

Notable differences between cantons

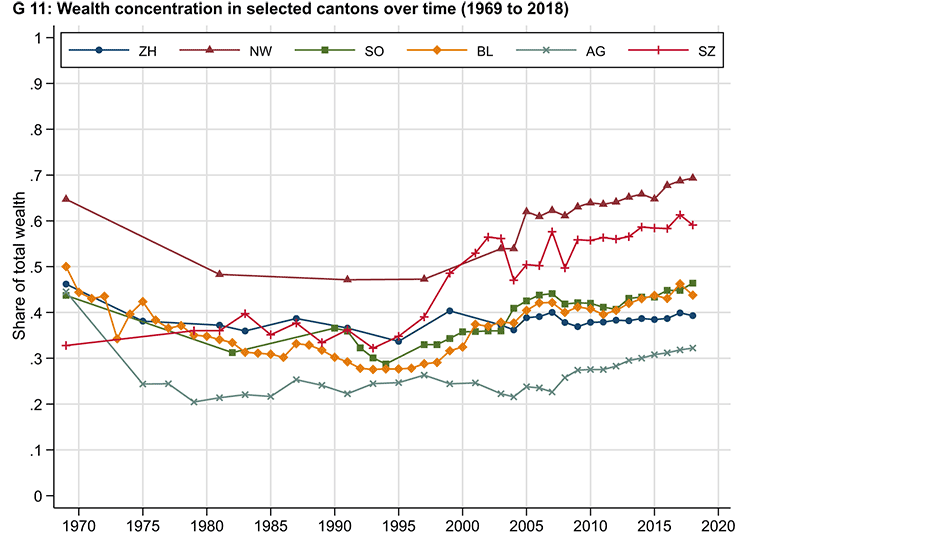

Based on wealth tax statistics from cantonal archives, the authors of the study have created new time series for the concentration of top wealth in each of the 26 Swiss cantons since 1969. Among the overall increase in wealth concentration at the national level – where the richest 1 per cent accounted for 43 per cent of total wealth in 2019 – there are notable differences between cantons both in terms of the level of wealth inequality within cantons and the trends between cantons (chart G11). While some cantons (such as Zurich) have seen a reduction in their richest 1 per cent’s share of assets in the last 50 years, others (such as Schwyz) have almost doubled this share.

As the cantons are free to set their own wealth tax rates, the question is to what extent these different trends are affected by differences in wealth tax. The authors have therefore compiled the relevant data on the top wealth tax rates. The cantons adjusted their top tax rates a total of 634 times between 1969 and 2018, with the overall trend being downward – albeit with considerable variations.

For example, the highest tax rate during the period analysed was 1.34 per cent in Glarus (1970) and the lowest was 0.13 per cent in Nidwalden (2014). Most tax reforms cut the top wealth tax rate by less than 0.1 percentage points, while the 10 per cent of reforms with the biggest changes were accompanied by a reduction or increase of at least 0.05 percentage points.

Dynamic effects of wealth taxes on cantonal wealth inequality

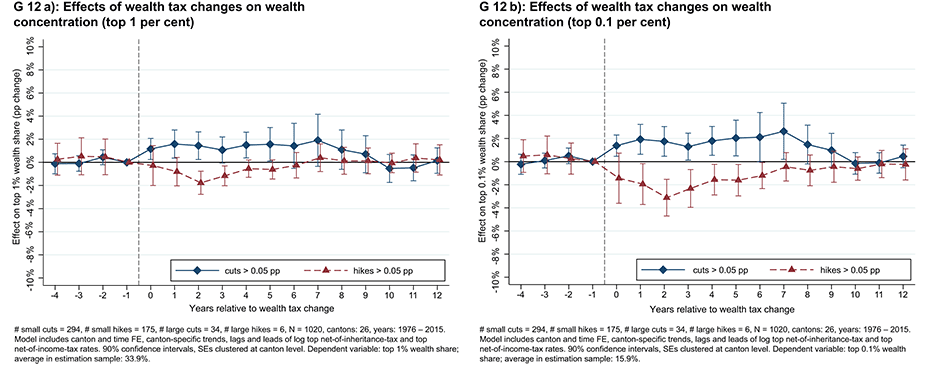

Using event studies, the researchers estimate the dynamic effect of cantonal wealth tax reforms on the subsequent changes in top wealth shares. They focus on major tax reforms and control for income and inheritance taxes. They find that reductions in the top wealth tax rate in a canton increase wealth concentration in that canton over the next decade, while tax increases reduce it (charts G12a and 12b).

The effect is particularly pronounced at the top of the distribution: for the top 1 per cent, a reduction of 0.1 percentage points in the top wealth tax rate increases the wealth share five years after the relevant reform by 0.9 percentage points (compared with the average wealth share of 34 per cent for the top 1 per cent). For the top 0.1 per cent, the wealth share increases by 1.2 per cent (with an average wealth share of 16 per cent).

Based on these estimates, the researchers conclude that the overall decrease in wealth tax progressivity from 1969 to 2018 explains around a fifth of the increase in wealth concentration among the top 1 per cent and a quarter of the increase in concentration among the top 0.1 per cent. The group of the wealthiest households that benefited most from the lower wealth tax rates at the top comprised only around 5,000 taxpayers in 2018 and is therefore relatively small.

Wealth tax cuts alone are not responsible for greater inequality

Although wealth tax cuts explain a large proportion of the growth in wealth concentration, other factors have obviously contributed to wealth inequality. Two aspects need to be considered here. Firstly, wealth taxes are not particularly progressive in any canton. The top tax rates are moderate compared with the proposals being discussed in the US.

Secondly, wealth taxes have relatively low exemption thresholds, starting at around CHF 100,000, which means that a large proportion of the population is affected. In fact, Switzerland’s wealth tax was never intended to achieve a comprehensive redistribution of wealth, but rather to generate stable revenues for the cantons and municipalities.

However, it is likely that other changes in Switzerland’s tax system over the last 50 years have played a significant role in the rise in wealth inequality. Firstly, the cantons have reduced the progressivity of income tax – in some cases very significantly.

Secondly, the continuous reduction in corporation tax at the federal and cantonal level was not included in this analysis, which focuses on wealth tax. This is relevant because the wealthy hold a large proportion of their assets in companies. And, thirdly, most cantons have abolished inheritance tax on direct descendants (Brülhart and Parchet, 2014); there is no inheritance tax at the federal level.

Inheritance accounts for a large proportion of the wealth of Switzerland’s super-rich. Baselgia and Martínez (2023) show that 60 per cent of the BILANZ 300 richest list for Switzerland recently acquired their wealth through inheritance. This proportion is extremely high compared with the Forbes 400 list for the US: 69 per cent of the richest Americans in 2018 were self-employed individuals who had founded their own businesses. Future research should aim to quantify the impact that these taxes have on wealth inequality.

The research article entitled ‘Does A Progressive Wealth Tax Reduce Top Wealth Inequality? Evidence from Switzerland’ by Samira Marti, Isabel Z. Martínez and Florian Scheuer, published in September 2023 in the Oxford Review of Economic Policy, is available here: external pagehttps://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grad025

References

Baselgia, Enea and Isabel Z. Martínez (2023). ‘Behavioural Responses to Special Tax Regimes for the Super-rich: Insights from Swiss Rich Lists’, EU Tax Observatory Working Paper No. 12. external pagehttps://www.taxobservatory.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/EU-Tax-Observatory_WP-12_Behavioral-Responses-to-Special-Tax-Regimes-for-the-Superrich_February2023.pdf

Brülhart, Marius and Raphael Parchet (2014). ‘Alleged Tax Competition: The Mysterious Death of Bequest Taxes in Switzerland’, Journal of Public Economics, 111 (C), pp. 63-78. external pagehttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2013.12.009

Saez, Emmanuel and Gabriel Zucman (2019). ‘The triumph of injustice: How the rich dodge taxes and how to make them pay’. WW Norton & Company.

Contact

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland