Demographic change: what are the implications for inflation?

Switzerland’s population is ageing. This article attempts to qualitatively assess the impact that this trend has on inflation. Its immediate effects are likely to be moderate. At the same time, there are risks: inflation could turn out to be higher but, surprisingly, it could also be lower.

Inflation was back at the centre of media attention last year. Supply shortages, energy prices, and monetary and fiscal policy were the main focus. However, there are also voices warning of higher inflationary pressures in the longer term caused by structural change such as demographics (see, for example, Goodhart and Pradhan, 2020).

Demographic change in Switzerland

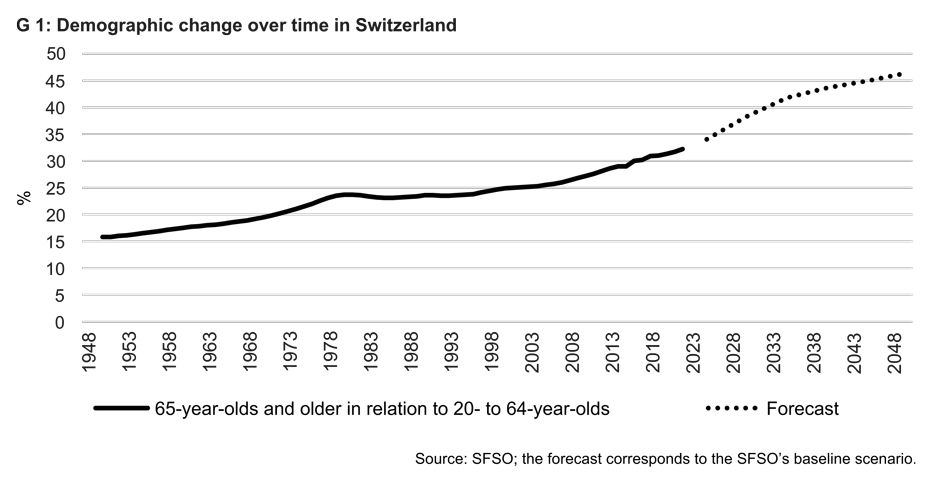

Demographic change reflects two trends. Firstly, the working population is growing less sharply. The Swiss Federal Statistical Office (SFSO) estimates that the population between the ages of 20 and 64 will increase by only 8 per cent in total over the next 30 years. By comparison, this demographic group grew by more than 30 per cent between 1950 and 1980 and between 1980 and 2010. Secondly, the population of retirement age will grow much more sharply – according to the SFSO estimate, by a total of 60 per cent over the next 30 years. Such forecasts are, of course, fraught with uncertainty, especially because the effects of migration are difficult to predict. If this forecast is correct, however, it means that in 30 years’ time there will only be just over two people of working age for every person over 65 (see chart G1). At the turn of the millennium there were four people of working age. After the Second World War the corresponding figure was more than six people.

Ageing is creating moderate inflationary pressures

Demographic change itself obviously generates inflationary pressures. This is because demographic change inhibits long-term economic growth. Let us assume for a moment that the central bank does not alter its monetary policy such that the money supply increases by a few per cent every year. Let us also assume that the economy stagnates owing to demographic change. In this situation the central bank creates more money than is needed for transactions in the economy and thus the money devalues: inflation occurs. Demographic change thus stokes inflationary pressures, assuming that monetary policy remains unchanged.

Why might demographic change inhibit growth? Long-term growth is determined by the growth of production factors (capital and labour) and their efficiency (‘multi-factor productivity’). Long-term growth is thus directly dampened by a stagnating labour force, as the labour factor grows less. Moreover, productivity could also be adversely affected. Firstly, studies show that countries with a larger share of their populations between the ages of 40 and 49 are more productive (Feyrer, 2007). Given demographic change, this age cohort will grow less than in the past. Secondly, it is possible that younger generations will increasingly be working in sectors that provide care for an ageing population (e.g. social care). In these sectors, however, the potential for productivity gains may be limited (see Goodhart and Pradhan, 2020).

However, direct inflationary pressures through these channels are likely to be relatively small for three reasons. Firstly, even if economic growth were to fall from 1 per cent to 0 per cent, i.e. the economy were to stagnate completely, inflationary pressures through these direct channels would be likely to increase by only 0.5 to 1.5 percentage points. Secondly, demographic change could also lead to the greater use of robots, which could generate productivity gains (Acemoglu and Restrepo, 2021). It is also likely that artificial intelligence will be rapidly deployed in sectors where labour shortages are pronounced (Baily et al., 2023). And, finally, the growth of the labour force, as well as labour productivity, also depends on the number of foreign workers and their skills.

The role of monetary policy

The direct inflationary pressures emanating from demographic change are thus likely to be moderate. However, we cannot conclusively assess the impact on inflation in Switzerland without discussing the role of monetary policy. After all, the Swiss National Bank (SNB) ensures price stability in accordance with its legal mandate. Following the logic of our thought experiment, this means that if a stagnating economy were to stoke inflationary pressures, the SNB would create less money to stabilise inflation in the medium term. The SNB has shown over the past 25 years that this is possible (see Kaufmann, 2019).

Are there reasons to believe that demographic change will nevertheless lead to higher inflation? Goodhart and Pradhan (2020) argue that the implicit debt incurred by the government owing to promised healthcare and social benefits is unsustainable for an ageing population. Consequently, policymakers will try to cover this debt by introducing an inflation tax. In this scenario the central bank effectively loses its independence. Although this possibility cannot be completely ruled out, Switzerland is well placed with its independent National Bank and its debt brake to prevent such fiscal dominance.

A slightly less often considered possibility is that the central bank misjudges the structural changes in the economy and thus unintentionally implements an overly expansionary monetary policy (see, for example, Orphanides and van Norden, 2002). This could happen, for example, if the central bank mistakenly attributes weak economic growth to stagnating demand for goods and services and thus fears deflationary tendencies. This would therefore lead to an overly expansionary monetary policy and rising inflation.

However, there are also reasons to believe that demographic change can lead to deflationary trends. A stagnating economy is associated with low interest rates (see, for example, Eggertson et al., 2019). This is because the interest rate reflects the expected return on an investment, which is higher in a strongly growing economy than in a stagnating economy. However, this also means that the central bank cannot lower short-term interest rates sufficiently during a recession because of the effective interest-rate floor, and so prolonged deflationary episodes occur. In extreme cases there is even a risk of drifting into a deflationary trap (see Benhabib et al., 2002).

What have we learned?

This article asks a simple question: does demographic change lead to inflation? The answer is complex. Viewed in isolation, it seems clear that labour shortages have an inflationary effect. According to Goodhart and Pradhan (2020), a scarcity of workers will cause wages to rise. These higher wages are then passed on to the prices charged by firms. However, this argument does not take account of the fact that the economy adjusts to new situations in the long run. Moreover, this argument ignores the monetary policy response.

It is therefore unclear whether demographic change actually leads to higher inflation. The example of Japan demonstrates that a rapidly ageing population, very low migration, a stagnating economy and an enormously high level of debt have not fuelled higher inflation for some time. Only time will tell whether this will also be the case in Switzerland and other countries.

------------------------------

1This thought experiment serves to isolate the effect of demographic change. The role of monetary policy is discussed in the next section.

2This estimate is based on a rough calculation using existing estimates of the demand for money in Switzerland.

References

Acemoglu, D. und P. Restrepo (2021): Demographics and Automation. The Review of Economic Studies, 89(1): 1–44.

Baily, M. N., E. Brynjolfsson, und A. Korinek (2023): Machines of Mind: The Case for an AI-Powered Productivity Boom. Brookings Institution, Retrieved from external pagewww.brookings.edu/articles/machines-of-mind-the-case-for-an-ai-powered-productivity-boom/.

Benhabib, J., S. Schmitt-Grohé, und M. Uribe (2002): Avoiding Liquidity Traps. Journal of Political Economy, 110(3): 535–563.

Eggertsson, G. B., M. Lancastre, L.H., und Summers (2019): Aging, Output Per Capita, and Secular Stagnation. American Economic Review: Insights, 1(3): 325–42.

Feyrer, J. (2007): Demographics and Productivity. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 89(1): 100–109.

Goodhart, C. und M. Pradhan (2020): The Great Demographic Reversal: Ageing Societies, Waning Inequality, and an Inflation Revival. Palgrave Macmillan.

Kaufmann, D. (2019): Nominal stability over two centuries. Swiss J Economics Statistics 155(7).

Orphanides, A. und S. van Norden (2002): The Unreliability of Output-Gap Estimates in Real Time. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 84(4): 569–583.