New incentives for antibiotics research and development

An estimated 33,000 people die in the European Union every year as a result of being infected with antibiotic-resistant germs. The number of deaths associated with antimicrobial resistance worldwide is estimated to be more than 5 million per year. New antibiotics urgently need to be developed, but this is often not profitable for companies. This article discusses a dynamic funding model that would make it more attractive for firms to develop new antibiotics.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is increasingly posing problems for healthcare systems around the world. In the EU alone, antibiotic-resistant bacteria are responsible for around 33,000 deaths every year, according to a 2018 external pageECDC study estimate. The associated healthcare costs and lost productivity amount to at least 1.5 billion euros annually. A external pagestudy published last year by the international research team Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators showed that antibiotic resistance was directly responsible for more than 1 million deaths in 2019 and is associated with nearly 5 million deaths worldwide. This makes the global AMR crisis as impactful as HIV or malaria, and potentially more serious.

High development costs and the risk of resistance create a dilemma

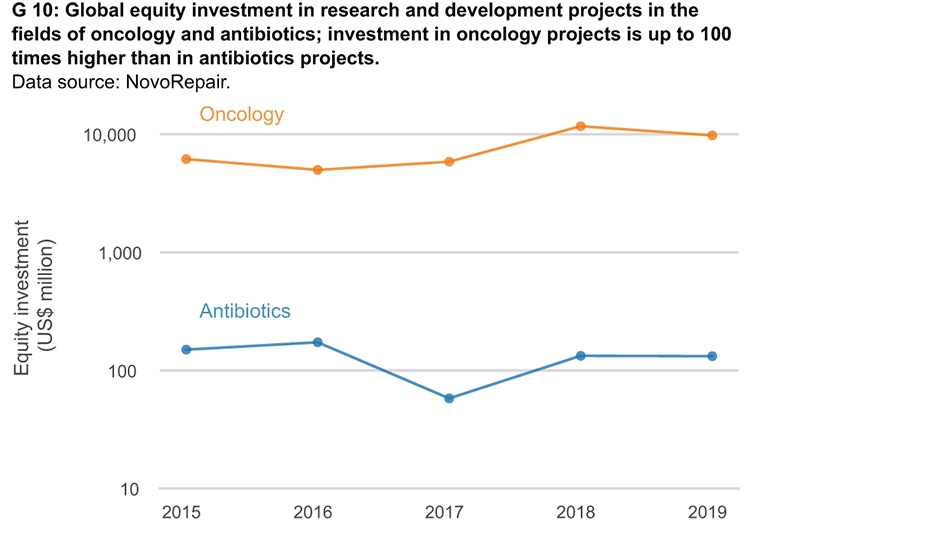

Despite the enormous impact of AMR, this global health crisis is nicknamed the ‘shadow pandemic’. Compared with COVID-19 and other infectious diseases, the spread of resistance and its effects on health systems are occurring on a slower time scale. One of the biggest challenges in the AMR crisis is a dysfunctional research and development (R&D) market for antibiotics, which means that not enough new antibiotics are being developed to treat resistant strains of bacteria. As with all pharmaceutical products, antibiotics are very costly to develop, but the use of new antibiotics should often be limited in order to slow the emergence of new resistance. This dilemma means that it is not profitable to produce antibiotics under existing market conditions. Various measures have been taken to address this problem. In this paper we discuss further steps to help boost activity in the R&D market for antibiotics.

Incentive schemes for the antibiotics market

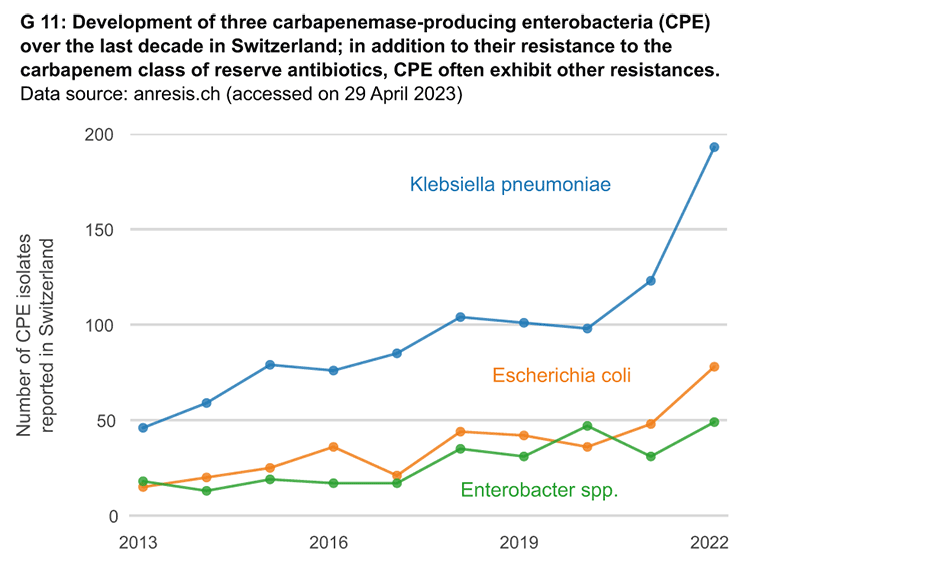

No new, significant classes of antibiotics have achieved market approval for more than three decades now. A steady increase in resistance to so-called ‘reserve antibiotics’ is being observed. These were developed specifically to be used against originally rare, multi-resistant germs.

There are few opportunities and many risks when pharmaceutical companies invest in antibiotics research and development. The cost of pharmaceutical research and development can amount to significantly more than 1 billion US dollars per drug, and there is only a small chance that potential drugs will eventually make it to market. Moreover, unlike other drugs, new antibiotics should be used as little as possible after market approval in order to slow the development of resistance.

Various push and pull incentives can be used to solve this market problem. Push incentives include, for example, financial support for biotech start-ups that research and develop antibiotics. These support services are essential for many small firms operating in this field. In addition, pull incentives on the way to market approval are an option. One possibility is the payment of premiums after successful market approval. Acting in its role as current G7 chair, Japan is working with international partners to draft a proposal for a global pull incentive scheme. In the United States the PASTEUR Act has been discussed for several years as a mechanism for creating targeted pull incentives worth billions of dollars. Similar initiatives introduced in Switzerland in 2019 and 2020 were rejected by the country’s Federal Council, which cited the enormous costs that international cooperation and financing would incur.

In addition to implementing push and pull incentives, it is important to ensure that antibiotics are targeted and not misused. The overuse of antibiotics in medicine, and especially in agriculture, is a major driver of the AMR crisis. For this reason, the United Kingdom’s National Health Service (NHS) has been testing a subscription-based payment model – also called the ‘Netflix’ model – for just over two years. Instead of paying for the quantity of antibiotics sold, the NHS compensates pharmaceutical companies for the development costs after market approval by making a one-off payment. The expected benefit of a new antibiotic for patients and the healthcare system as a whole is remunerated.

Subscription payments decouple pharmaceutical companies’ profits from their sales volumes. They have the potential to boost antibiotics research and development, even if sales of new antibiotics remain low, because such drugs are mainly used as a reserve against resistant bacteria.

A dynamic funding model

An incentive scheme developed by Hans Gersbach (KOF) and Lucas Böttcher (Frankfurt School of Finance & Management) proposes a financing model that, unlike subscriptions, does not rely on public funding. This is a dynamic incentive scheme that simultaneously addresses three problems: (1) reducing the excessive use of antibiotics, (2) stimulating research and development, and (3) supporting the targeted use of antibiotics against resistant bacteria.

The basis of this incentive model is a fund, established by countries forming an ‘antibiotics club’, such as the AMR Action Fund. This fund would be financed by fees levied on each unit of antibiotics used outside the scope of human medicine. In the language of economics, this is a ‘Pigou tax’. This money would be used to partially reimburse pharmaceutical and biotech companies for their research and development expenses when they bring a new antibiotic to market.

Refunds consist of a fixed part and a flexible part. The fixed part would be a general premium for introducing an antibiotic in the market. The flexible part would be higher if an antibiotic could be used to treat bacteria caused by resistant bacteria. It would be lower if a new antibiotic were used but the infection could be treated using existing antibiotics.

Incentives for ‘narrow-spectrum’ antibiotics

In addition to encouraging research and development of antibiotics, this model could be used to create incentives for so-called ‘narrow-spectrum’ antibiotics. These are antibiotics with relatively small potential markets but high efficacy against certain previously resistant strains of bacteria.

Regulators would need to set payout amounts and other parameters for the reimbursement scheme to stimulate research and development while preventing pharmaceutical companies from making excessive profits. Monitoring antibiotic use for non-resistant strains would require storage of prescription and anonymised diagnostic test data. Various AMR monitoring systems already exist at national and international level and could be expanded accordingly.

We call our proposal a ‘reimbursement scheme’. The public cost of antibiotic use, such as the development of resistant bacteria, is borne by polluters in the form of levies. Revenue is returned to research and development initiatives aimed at eliminating these negative effects. Unlike the NHS subscription model, reimbursement schemes are self-funding. They also ensure that firms focus their research and development on resistant bacteria from the outset.

Such refund approaches are already being used in environmental policy to encourage companies to reduce pollutants. Sweden has been taxing nitrogen oxide emissions since 1992 by using a refund designed to generate a net gain for the cleanest energy producers. Switzerland has levied a tax on carbon dioxide emissions that is linked to a partial refund.

In some critical areas it may make sense to allocate research and development projects to areas that are crucial to society in the long term. Their successful application would therefore allow the wider use of such systems to promote research and development for the treatment of other diseases.

Conclusions

Financial incentives and close international cooperation are needed in order to make the development of new antibiotics commercially viable for companies. It is also important to apply the polluter-pays principle to the antibiotics crisis. In concrete terms this means that antibiotics users pay a fee according to their consumption if the antibiotics are used outside the scope of human medicine. This fee is used to create market incentives and promotes the targeted use of antibiotics. This ensures that more funds are available for research into new antibiotics and fewer resistances develop. The establishment of a reimbursement scheme as part of an antibiotics club of several countries naturally needs intergovernmental organisation as well as a suitable set of rules and control, which is not easy to achieve in today’s geopolitical climate. It might therefore be appropriate for the antibiotics club to start with a few economically strong OECD countries. Even for such a club this poses some challenges that still require further research. And, last but not least, the ethical question of how other countries gain access to the new antibiotics would need to be resolved.

In addition to the incentive problem in the R&D market, other problems need to be addressed at national and international level: these include reducing the misuse and overuse of antibiotics; developing rapid diagnostics, vaccines and alternative treatments; and improving the implementation of infection-prevention protocols in facilities such as hospitals. These measures are complementary to the R&D market incentive schemes. It is expected that both sets of measures will be needed to successfully combat the shadow pandemic.

Literature references:

Böttcher, L., H. Gersbach, & D. Wernli (2022): Restoring the antibiotic R&D market to combat the resistance crisis. Science and Public Policy, 49(1), 127-131.

Böttcher, L. & H. Gersbach (2022): A refunding scheme to incentivize narrow-spectrum antibiotic development. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology, 84(6), 59.

Contact

Makroökonomie, Gersbach

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

Frankfurt School of Finance & Management