How dependent is Swiss industry on China?

One-fifth of Swiss industrial companies are moderately to heavily reliant on critical inputs from China. Their greatest dependence is in the electronics sector, followed by the pharmaceuticals and chemicals sectors. Just under one-fifth of firms are unable to assess their own reliance. The measures already taken or those that are planned reveal that production and procurement are being redirected towards Europe and Switzerland. These are among the findings of a KOF company survey.

China’s zero-Covid policy has severely tested the performance and reliability of global supply chains in recent years. In addition, tensions between China and the United States have increased geopolitical uncertainty. Both have led to economic relations with China being put to the test in many Western countries.

This is not about a complete decoupling from China but about the reduction of critical dependencies (‘de-risking’), which could result in production losses or massively higher costs for companies and, in the worst-case scenario, might even endanger the security and stability of one’s own country. Germany’s reliance on Russian gas has shown just how critical economic interdependencies can be in the event of conflict.

In order to document Swiss firms’ reliance on China, KOF surveyed Swiss industrial companies between 1 March and 3 April on their direct dependence on China – either through their direct purchases of critical products from China or through their indirect dependence via their supply networks. Critical products are defined as inputs that are necessary for production and cannot be replaced or procured elsewhere within a reasonable period of time and at reasonable cost. In addition, KOF wanted to know what measures firms had taken or planned within the last two years to reduce these dependencies.

Moderate reliance on critical inputs from China reveals sectoral variations

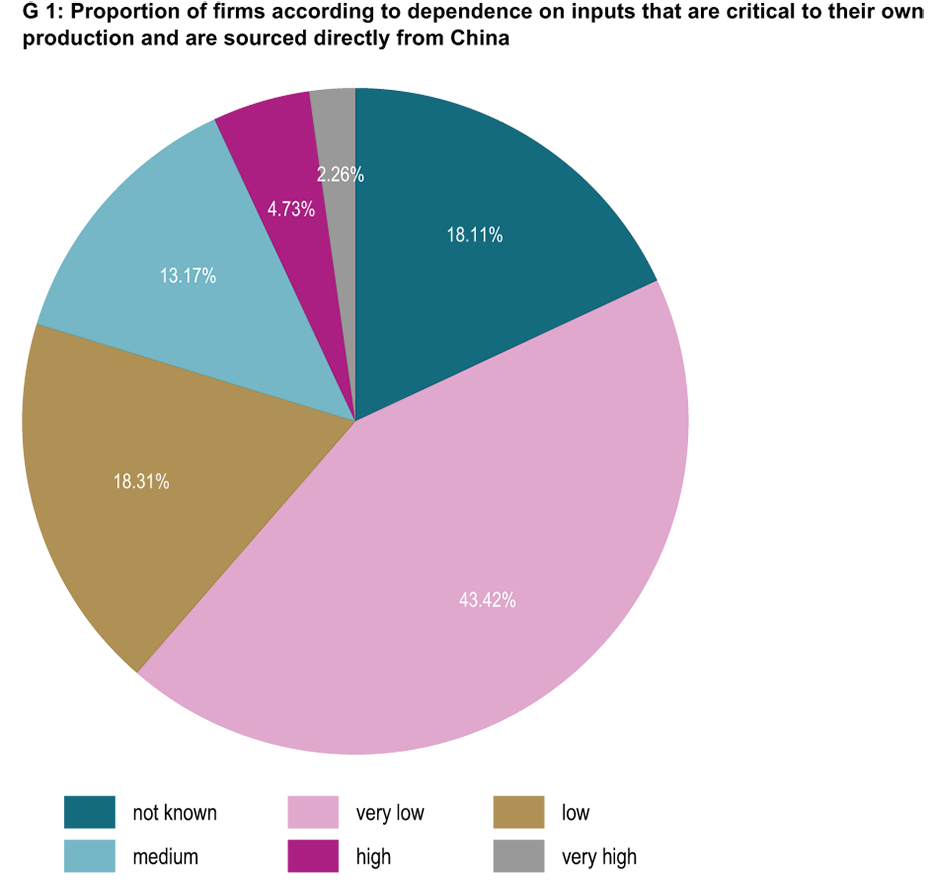

An evaluation of the 486 responses received shows that Swiss industry’s reliance on critical inputs from China is moderate overall. However, 7 per cent of the companies surveyed are strongly or very strongly dependent on Chinese intermediate inputs, while more than one-eighth indicate a medium level of dependence (see chart G 1). It is noteworthy that 18 per cent of firms are unable to assess their degree of reliance on Chinese inputs.

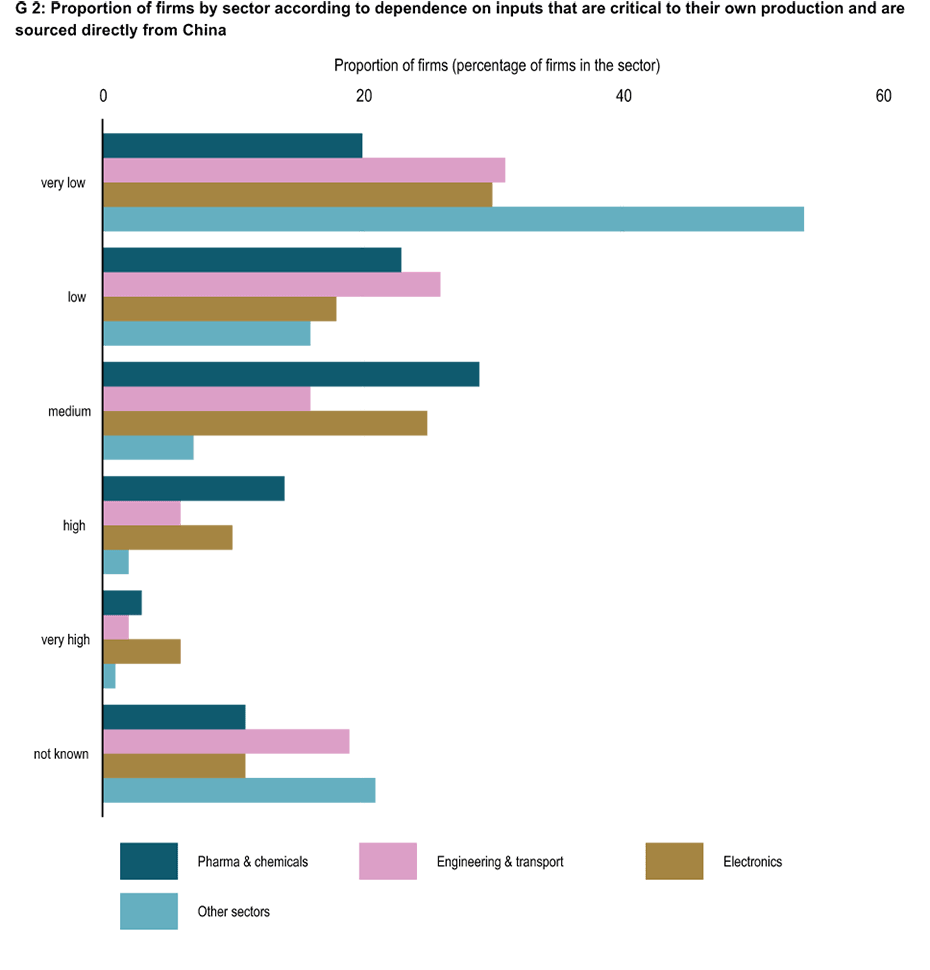

The proportion of critical inputs from China is particularly high in the electronics industry (see chart G 2). More than half of companies in the pharmaceutical and chemical sectors estimate their dependence to be medium or higher, while in engineering and transport it amounts to a quarter of firms. Roughly one-fifth of companies in the engineering and transport sectors as well as firms in other sectors cannot estimate their direct dependence on China.

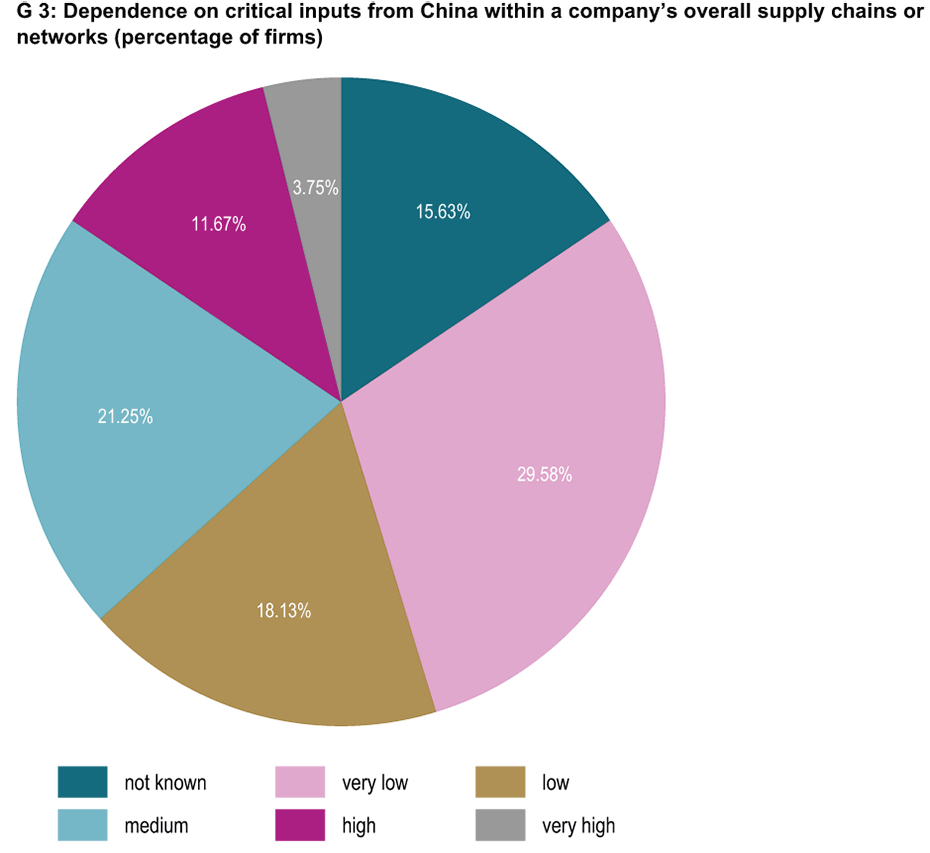

Indirect dependence on China via a company’s supply network is slightly higher than direct reliance on Chinese inputs (see chart G 3). More than one in seven firms sources inputs from supply networks that are highly or very highly dependent on China. While overall more than one-third of companies report having at least medium reliance in their supply chains, fewer than one-third of firms report not using critical inputs from China in their supply chains. One in seven companies are unable to assess their dependence on China in their supply chains.

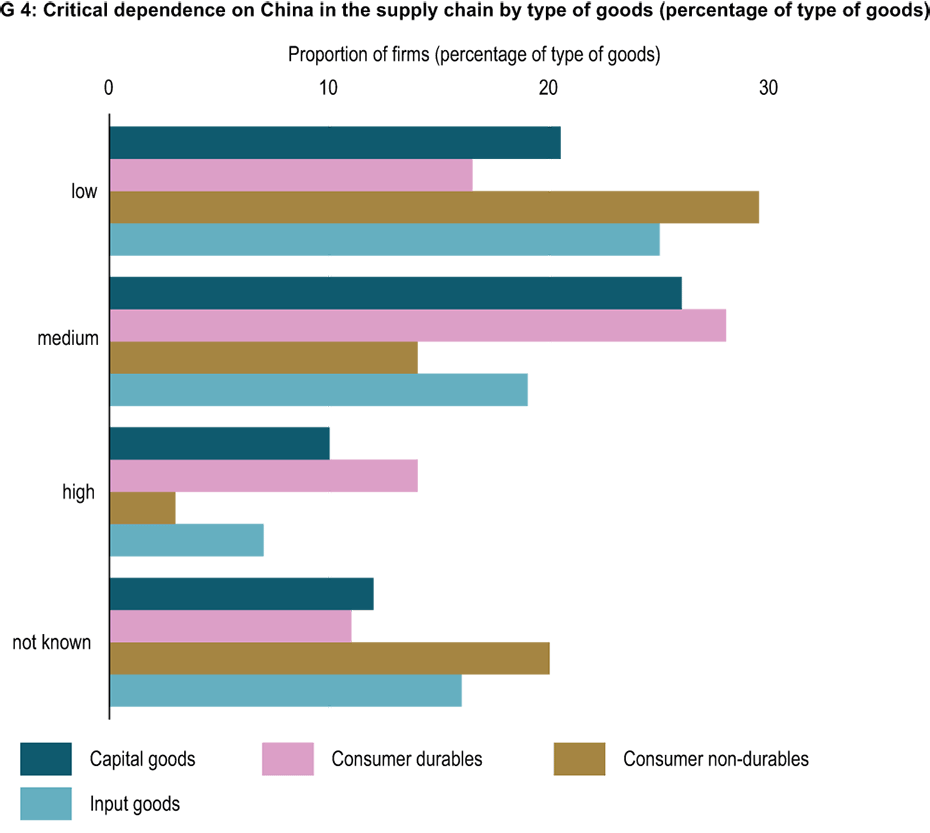

More than one in ten companies producing durable goods or capital equipment report high levels of reliance on China in their supply chains, while more than a further quarter of these firms state that their level of dependence is moderate (chart 4). Although the level of reliance appears to be generally lower for consumer goods and intermediate products, these companies are less aware of their dependencies.

A wide range of measures to reduce critical dependence on China

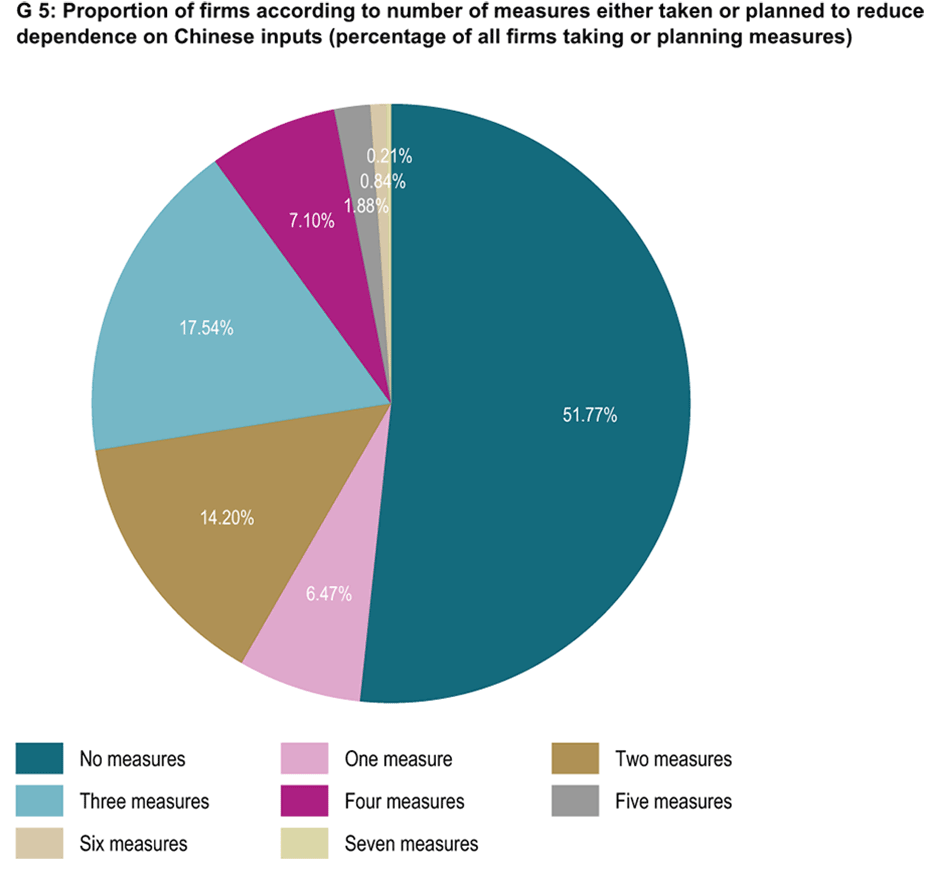

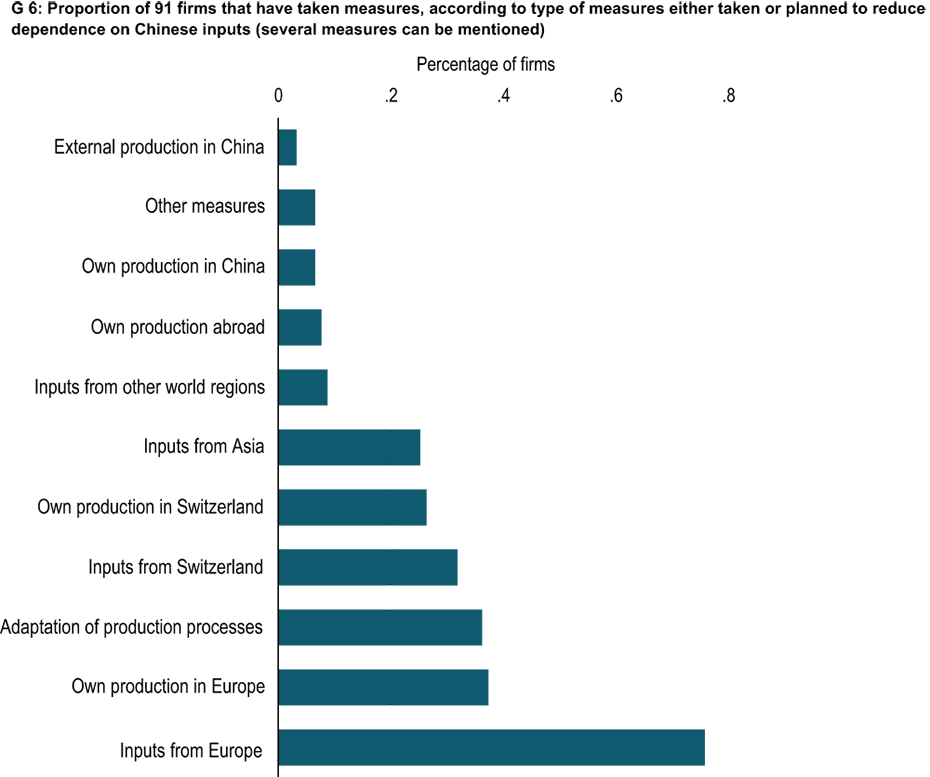

How do firms deal with these dependencies? Overall, more than half of companies have not taken any measures, while just under a third of firms have either taken or planned up to three measures (see chart G 5). One in ten companies has either taken or planned four or more measures. Focusing on the 91 firms either taking or planning measures, the chart below shows the types of measures taken or planned by these companies according to their frequency (see chart G 6). Four out of five firms are planning to purchase more inputs from Europe or are already doing so, while just under 40 per cent of the companies intend to produce more in Europe. Almost as many firms are adapting their production processes.

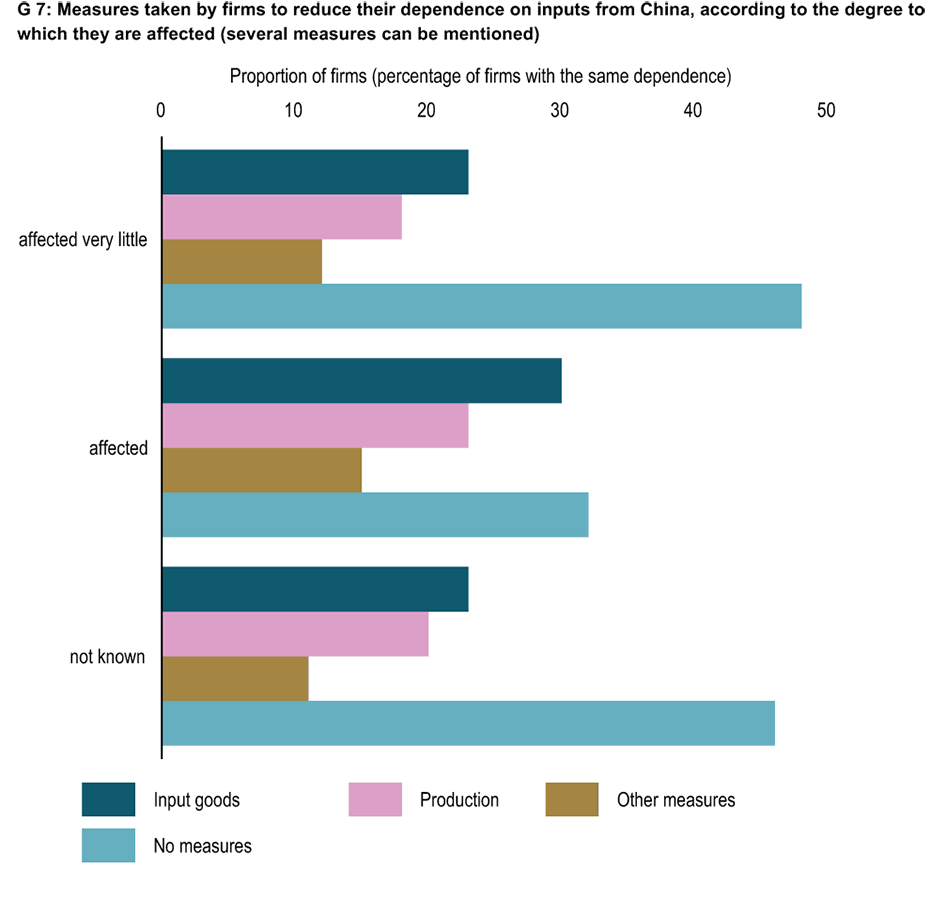

More than one in four companies are either producing or purchasing more inputs from Switzerland or from Asia, excluding China (or they plan to do so). Other measures such as sourcing inputs from other regions of the world, warehousing goods, and focusing on external or proprietary production in China are significantly less popular. Less severely affected and moderately to severely affected companies have either opted for or are planning similar measures, with the proportion of firms taking no measures at all falling to 30 per cent as their dependence on China increases (see chart G 7). The most popular strategy across all affected groups is to take no action at all, followed by geographic adjustments to the procurement and production of inputs.

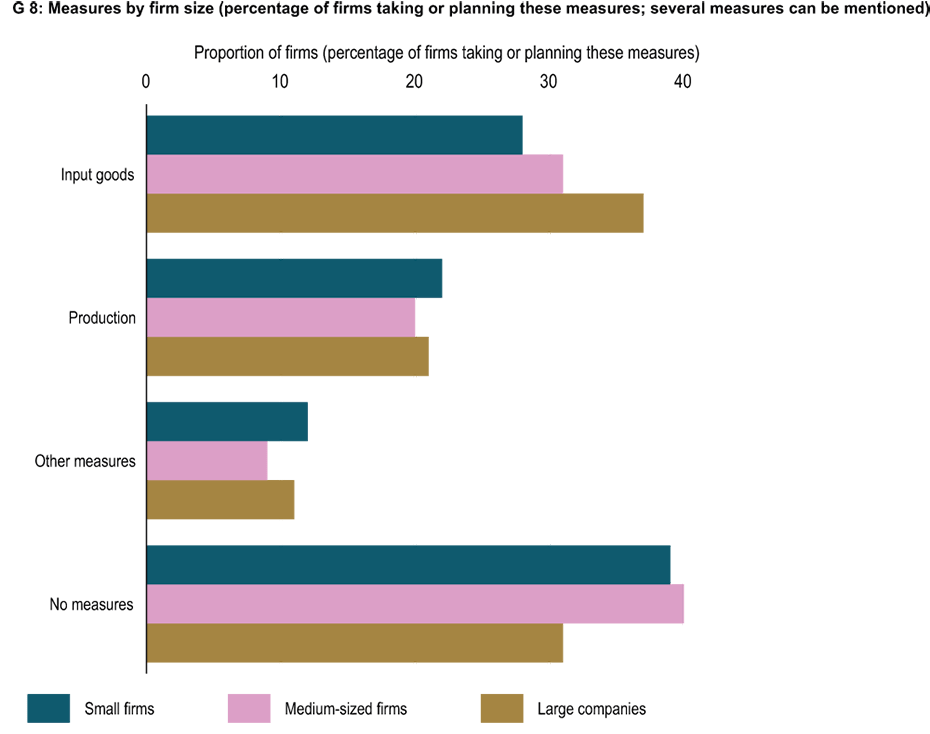

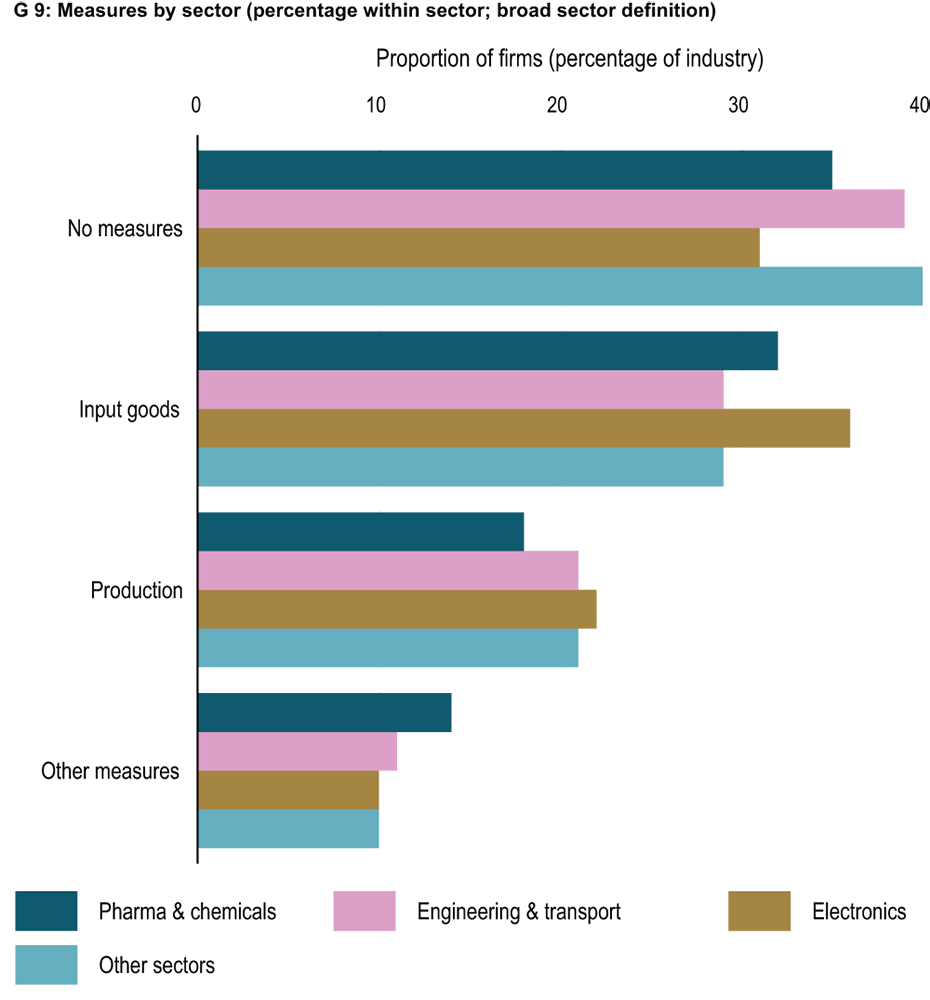

It is noteworthy that even companies without any exact knowledge of their dependency are taking measures. The choice of these measures appears to be fairly unrelated to the size of the firm concerned (see chart G 8). Almost 60 per cent of large companies are altering or plan to alter the sources of their intermediate inputs, while smaller firms are more likely to adjust their production processes or opt for other measures such as greater warehousing. More than 40 per cent of small and medium-sized enterprises, on the other hand, are not taking any measures at all. The measures of the sectors are comparable: except for the electronics sector, it is most popular to take no measures (30-40%), followed by changes in input purchasing, which is most pronounced for the electronics sector with well over one third (see chart G 9).

The international debate on critical dependencies

These findings should be seen against the backdrop of the current debate about reliance on China in critical areas that is currently taking place in Europe and, especially, in Germany. For example, a external pagestudy published at the beginning of this year by the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW) showed that the German economy’s dependence on imports from China (and Taiwan) is lower than the trade statistics would suggest. However, China dominates the markets in individual raw materials and products, especially in the electronics sector, and the world market and German supply chains could not replace China as a supplier in the short term.

Against the backdrop of its dependency on certain raw materials, the European Union adopted a external pagestrategy in March to rapidly diversify the countries of origin of (refined) raw materials. Demand for many minerals and metals is expected to surge as a result of the energy transition and the growth of digital technology. Swiss companies should therefore keep an eye on any critical reliance on individual suppliers and, possibly, unreliable countries of origin. This would enable them to take appropriate and proportionate measures to mitigate the risk of mission-critical dependencies if necessary, as has often been done successfully in the past.

China and world politics: three insights

At the virtual event entitled ‘KOF Beyond the Borders’ on 26 May, Markus Herrmann, co-founder and Managing Director of the China Macro Group, Lars Brozus, Deputy Head of the Global Issues Research Group at Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, and KOF economist Vera Eichenauer discussed the topic of ‘Power shifts in the world system: what role does Europe play?’. The event was moderated by KOF staff member Sina Freiermuth. We have summarised the three most important findings of the discussion.

From multilateralism to multiple crises – historical evolution:

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, a ‘period of détente’ prevailed on the world political stage in the 1990s, according to Lars Brozus’ analysis. Even Russia and China showed themselves to be cooperative during this time, for example, when it came to environmental issues or women’s rights. Multilateralism – i.e. several states working together to solve political, social and technical problems – worked relatively well. Examples of this were the UN Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 and the UN World Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995. China even joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001.

As Lars Brozus explained during the further course of his presentation, however, world politics entered a period of increasing turmoil from the turn of the millennium onwards. Above all, the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001 and the financial crisis unleashed in 2007 tipped international relations and the global economy into a state of disequilibrium. The Arab Spring, the so-called ‘colour revolutions’ in Georgia and Ukraine and Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 also changed the geopolitical situation. The United Kingdom’s exit from the European Union in 2020 (‘Brexit’) and the ‘America first’ policy pursued by the then (2017-2021) US President Donald Trump challenged multilateralism not only practically but also conceptually.

By the time the COVID-19 pandemic had begun in 2020, according to Brozus, we found ourselves in an age of multiple crises. This had three characteristics: the replacement of the multilateral world order by a multipolar one, as the systemic rivalry between the US and China and the war in Ukraine illustrate; a connectivity crisis that exposes the weaknesses of the global division of labour, as exemplified by pandemic-related supply chain problems; and finally, global transformation challenges characterised by the need to manage climate change and sustainable development, which puts social cohesion in many countries under pressure.

The Taiwan conflict – seven scenarios:

The rivalry between China and Taiwan currently poses one of the most important geopolitical risks alongside the war in Ukraine. In his presentation, Markus Herrmann outlined seven scenarios of how the conflict could develop. First, there was speculation about the possibility of a swift invasion triggered by political factional infighting within the party leadership before the 20th party congress in October 2022, although this did not materialise (scenario 1). Other scenarios include an invasion launched in 2027, once China has achieved the formal goal of modernising its armed forces according to the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) (scenario 2), and a non-military negotiated settlement in the 2030s, in which China could bring its economic and political might to bear (scenario 3).

Furthermore, events outside China could introduce a new dynamic into the conflict, such as a change of government in the US in 2024 or 2028 (scenario 4) or a strengthening of the independence movement in Taiwan’s elections in the same years (scenario 5). But there are also scenarios in which the status quo is perpetuated, namely if a mutual deterrence equilibrium is achieved in the long term (scenario 6) or if the conflict is de-escalated thanks to the adoption of a less aggressive and more friendly policy stance in Beijing and Taipei (scenario 7).

Addressing these scenarios, Markus Herrmann finally mentioned various reasons why, in his view, we are unlikely to see any short-term escalation in the Taiwan Strait. These include the fact that military deterrence seems to be working; there are still critical dependencies on Taiwan’s production of semiconductors in particular; China’s military has not yet been modernised; the outcome of Russia’s war against Ukraine is not yet clear; there are serious conflicts between these objectives and the domestic priorities of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership; the Communist Party’s preference for a non-military solution remains unchanged; and, finally, Wang Huning, a senior politician in the CCP and a close adviser to Party Chairman Xi Jinping, has been entrusted with the task of devising an innovative Taiwan policy that aims to focus more on the interpersonal dimension.

The war in Ukraine and China’s role:

All experts agree that the systemic rivalry between China and the US is key to understanding the war in Ukraine and its potential resolution. While China is not supplying weapons to Russia, it has avoided officially labelling Russia as the aggressor and speaks trivially of a ‘Ukraine conflict’. This strategy of ‘pro-Russian neutrality’ is rooted in China’s dual dependence on both the West and Russia, with whom China shares a 4,000-kilometre national border. On the one hand, the Chinese economy is closely interconnected with the United States and Europe through globalisation. On the other hand, according to Markus Herrmann, China is also dependent on its neighbour and longstanding strategic partner Russia for energy, food and military supplies.

Contacts

Professur f. Wirtschaftsforschung

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

KOF Bereich Zentrale Dienste

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland