Wage increases as a response to the shortage of skilled workers

What factors influence wage levels in the various sectors? This analysis shows that, in particular, the extent of the shortage of skilled workers in an industry is positively correlated with the wage growth expected by companies.

Income earned from employment is the most important source of income for households. Since a large proportion of this income is spent on consumption, wages also have a major impact on the demand for goods and services. At the same time, they are an important cost factor for companies. Strong wage growth increases production costs and can reduce firms’ profits. The level of wages is thus crucial for economic growth. But what factors play a role in whether and how much wages change? Why do they rise more in some sectors than in others?

Large sectoral differences in expected wage growth

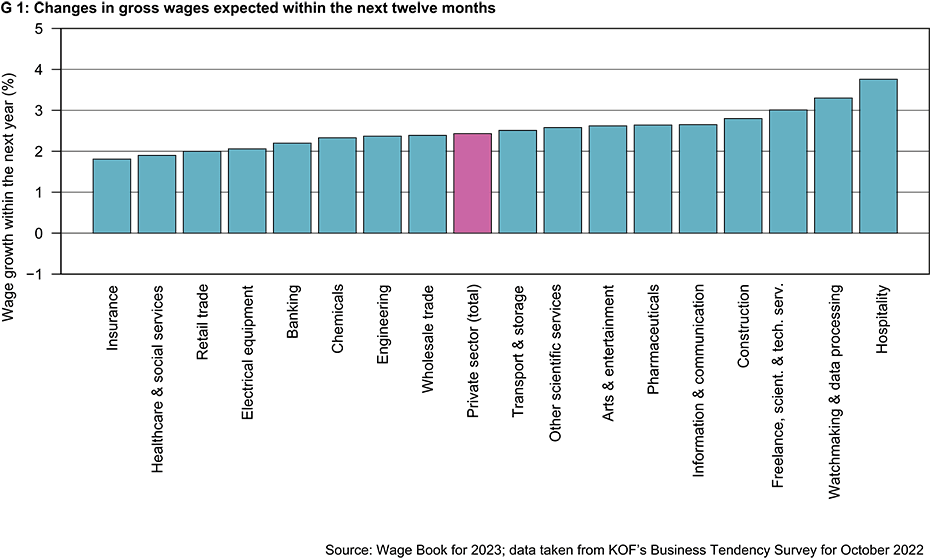

This analysis provides an initial insight into these questions on the basis of a business tendency survey conducted by the KOF Swiss Economic Institute at ETH Zurich in October 2022. This was the second time that this quarterly business survey was supplemented by a question on companies’ wage expectations. Around 4,500 firms from various sectors provided information on how gross wages in their organisation are likely to change over the next 12 months. These firms’ responses reveal large sectoral differences (see chart 1). While insurance companies expected average wage growth of 1.8 per cent, businesses in the hospitality industry expected to see wage growth of 3.8 per cent.

How can these differences between sectors be explained? The Swiss labour market was affected by various developments in autumn 2022 that may still be having an impact on wage growth: skilled-labour shortages, inflation, looming energy supply shortages as well as the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent recovery. Even though we are aware that we cannot analyse all of the factors potentially explaining the sector-specific differences in the wage levels expected in 2023, we would like to take a closer look at some of them.

First, the extent of the labour shortage. Sectors suffering from severe labour shortages may try to attract workers by raising wages. The data on labour shortages, like wage expectations, come from KOF’s Business Tendency Survey. Here, companies are asked whether their labour shortages present an obstacle to production. The corresponding indicator measures the proportion of firms claiming that labour shortages are hampering their production.

Second, the energy costs as a percentage of a company’s revenue. Firms with a high share of energy costs were hit particularly hard by the sharp rise in energy prices, which may have limited their room for manoeuvre in setting wages. The data on energy costs as a proportion of revenue come from the KOF Energy Survey 2015.1

Third, the current business situation and expected changes in the business situation over the coming months. Sectors in (what is expected to be) a better business situation are likely to have more scope for wage increases. These data also come from KOF’s Business Tendency Survey. Companies are asked how they would rate their current business situation (as ‘good’, ‘satisfactory’ or ‘poor’) and how their business is expected to perform over the next six months (to ‘improve’, ‘not change’ or ‘worsen’). The indicator of their current business situation represents the difference between the percentages of their ‘good’ and ‘poor’ responses. The indicator of their expected business situation constitutes the difference between the percentages of their ‘improve’ and ‘worsen’ responses.

Fourth, firms’ average profit margins in the pre-pandemic year of 2019 and in the COVID-19 year of 2020. Here, too, it can be assumed that industries with high margins have greater leeway in setting wages than sectors with low margins. These data come from the value-added statistics compiled by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office (FSO).

Fifth, the proportion of firms in industries that expect their (selling) prices to rise over the coming months. Even if they have low profit margins, companies can pay higher wages if they are able to raise their prices accordingly. This information also comes from KOF’s Business Tendency Survey. The indicator represents the difference between the percentages of companies that expect prices to rise and those that expect prices to fall.

Recruitment difficulties are an important factor in sectoral differences

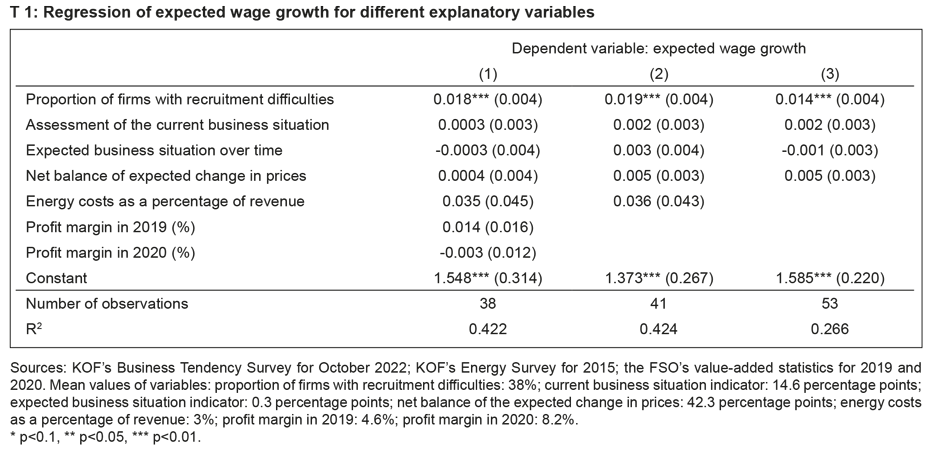

Table 1 shows the results of the multivariate regression of expected wage growth in an industry (at NOGA-2-digit level) for the above indicators. The various columns represent different specifications. The specifications for profit margin and energy costs have many missing values, which further reduces the already low number of observations. To increase the number of observations, these variables were removed from the regressions in columns two and three. The remaining coefficients are robust across all specifications.

This table shows that, in these three specifications, only the proportion of firms claiming that labour shortages are hampering their production shows a significant correlation with the projected wage growth in an industry. According to the specification in the first column, therefore, the expected wage growth in an industry increases by 0.18 percentage points if the proportion of firms with recruitment difficulties increases by 10 percentage points.

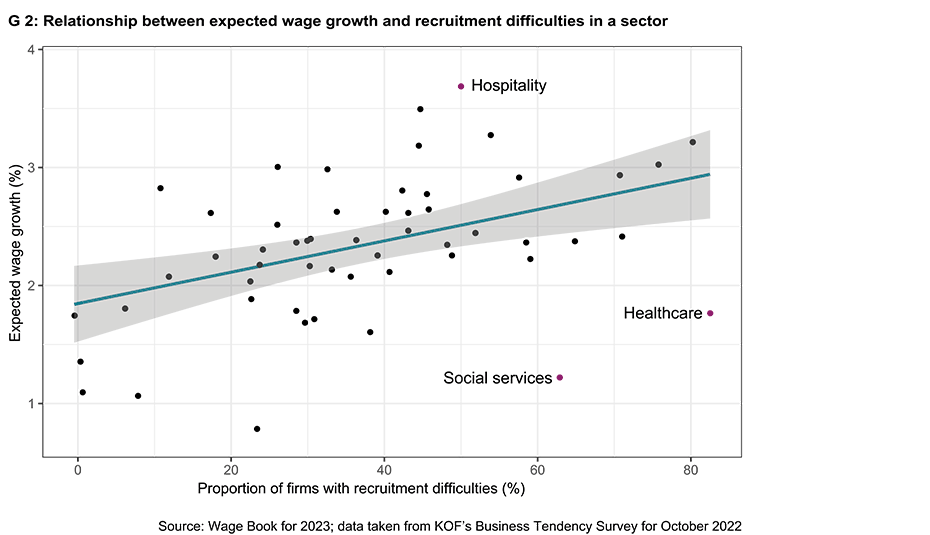

Chart 2 also illustrates this relationship visually. The larger the share of firms with recruitment difficulties in an industry, the stronger the wage growth they expect over the coming twelve months. This is understandable. In a market economy there is a simple solution to problems of scarcity such as labour shortages: companies must become more attractive so that more people want to work (for them). This can be achieved through better working conditions and/or higher wages.

Lack of leeway in price setting as a possible obstacle to wage growth

Do the other factors not play any role here? This conclusion would be premature. First, the number of observations is small, which limits the robustness of the conclusions. And, second, it is quite possible that individual factors are important for certain sectors, even if no general statistical correlation is evident in the above specification.

This is illustrated by comparing healthcare and social services with hospitality. These three sectors represent ‘outliers’ in chart 2: firms operating in both healthcare and social services expect to see weak wage growth despite pronounced labour shortages. Although the hospitality sector confirms the link between labour shortages and wage growth, the extent of the latter is exceptional. What distinguishes the hospitality industry from the healthcare and social services sectors?

Hospitality businesses suffered heavy losses during the COVID-19 pandemic and they have fairly low profit margins and comparatively high energy costs. This does not suggest that they will see sharp rises in wages, even if their business situation recovered in autumn 2022. But hospitality firms seem to have room for manoeuvre when it comes to pricing. The survey data show that the majority of companies in the hospitality industry expect their sales prices to rise. While these are mainly likely to be a result of higher energy and food costs, leeway in pricing helps to finance any wage increases as well.

The situation is different in the healthcare and social services sectors, were only a small proportion of actors expect to receive higher remuneration for their services. Accordingly, the scope for wage increases is limited. The problem is that this is likely to further exacerbate the already pronounced shortage of skilled workers. Other sectors that expect to see high wage growth – for example firms engaged in the manufacture of watches and data processing equipment – also reckon in most cases that they will be able to raise their prices.

It is striking that in many sectors where strong wage growth is expected, collective wage negotiations between trade unions and employers’ associations have taken place and have agreed high wage settlements by Swiss standards. At the beginning of June, for example, the parties to the collective labour agreement (CLA) signed for the hospitality industry agreed on full compensation for inflation and additional minimum wage increases of up to CHF 40 per month, which represents wage rises of between 3.5 per cent and 3.9 per cent. Wage increases averaging 3.5 per cent were agreed for the watchmaking industry in October, while effective wage rises of 3 per cent were agreed for the cleaning industry in German-speaking Switzerland in September.

Substantial pay hikes were also announced for the construction industry at the end of November after lengthy negotiations. These sectors are characterised either by high degrees of unionisation or by generally binding CLAs. The latter mean that all businesses in the sector must abide by the provisions of these CLAs even if they do not belong to the employers’ association that signed the agreements. This increases the likelihood that wage rises will be accepted, as there is no fear of falling behind domestic competitors who do not pay higher wages.

Conclusion

This analysis shows that the extent of any shortage of skilled workers in an industry is positively correlated with the wage growth expected by companies. This is understandable: firms that cannot find skilled labour try to become more attractive by raising wages. Exceptions include the healthcare and social services sectors, were companies do not expect to see above-average wage growth despite the pronounced shortage of skilled workers. This is probably due, among other things, to the fact that the payment of higher remuneration for services is difficult to enforce in these areas.

---------------

1More recent figures are not available. However, it can be assumed that the cost structure at sector level has not changed much in the past eight years.

Contact

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland