Although the outlook for the global economy is brightening, additional risks are emanating from the banking sector

The energy crisis has turned out to be less severe than feared – partly thanks to the mild winter. However, high inflation, rising interest rates and geopolitical risks continue to weigh on the global economy. This situation is compounded by the risk of disruption in the banking sector.

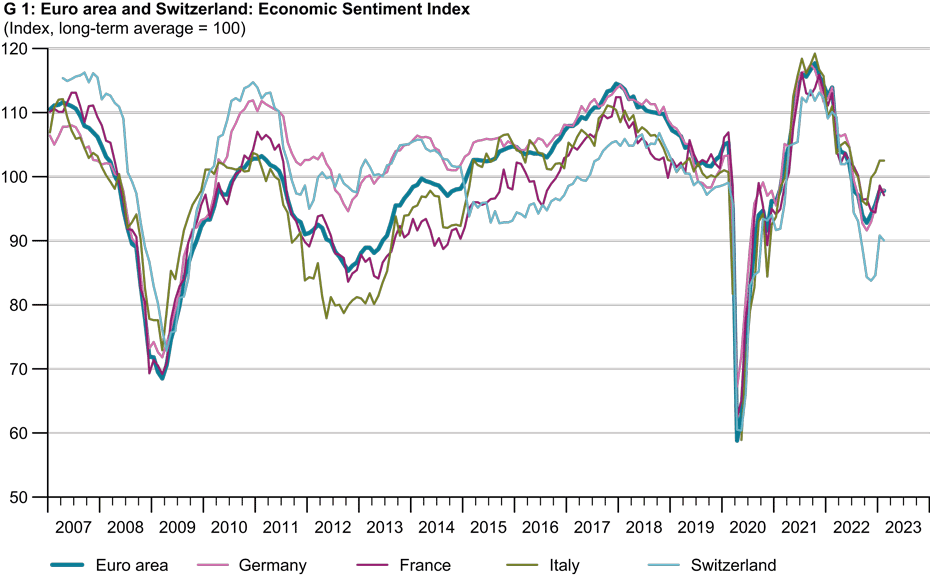

Since December 2022, key leading economic indicators for Europe have recovered after having fallen sharply – albeit from high levels – for several months (see chart G 1 entitled ‘Euro area and Switzerland: Economic Sentiment Index’). One reason for this is that the much-feared energy crisis was largely averted thanks to government intervention and a mild winter. In addition, the Chinese leadership performed a spectacular U-turn in December 2022: instead of its zero-COVID policy, a zero-restrictions policy is now being pursued. Accordingly, China is expected to see a recovery in the first half of 2023, which will have positive repercussions for the global economy. As a consequence of these developments, KOF is revising its forecast for global output upwards compared with its December forecast. Although there will probably be no stagnation in the first half of 2023, KOF continues to assume that global economic growth is likely to remain below average for the time being.

Global output growth in the final quarter of 2022 below average but higher than expected

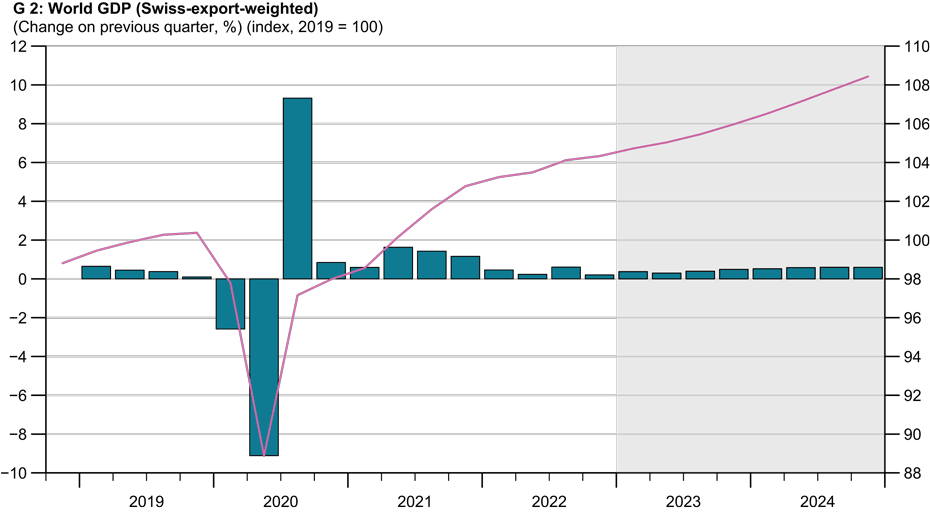

After Swiss-export-weighted global output had increased sharply in 2021 as a result of catch-up effects following the COVID-19 pandemic, only below-average growth rates were recorded in 2022 (see chart G 2 entitled ‘World GDP (Swiss-export-weighted)’). The reasons for this included international supply chain problems as well as the energy price spike and uncertainty arising from the war in Ukraine. Global output grew only modestly in the fourth quarter of 2022 especially. However, growth was somewhat higher than had been expected in KOF’s December forecast. US GDP in particular increased surprisingly sharply, with the saving ratio continuing to be significantly reduced and consumption thus remaining robust. In addition, a sharp drop in prices compared with the third quarter of 2022 caused a marked rise in inventory investment in real terms, which accounted for roughly half of the growth in GDP. Gross fixed capital formation, on the other hand, has been falling since 2022.

The increase in GDP in the European Union, which was marginal, was not far from the stagnation that had been forecast. GDP in Germany and Italy declined as expected, while in France and the United Kingdom it did not stagnate as expected but, rather, increased or decreased slightly. One reason for this decrease or only slight increase in output was low energy consumption as a result of the mild winter and energy-saving efforts.

There was no GDP growth at all in China in the fourth quarter (quarter-on-quarter). The stagnation there was due to weak consumption, which is likely to be a consequence of the country’s real-estate crisis, the steady increase in coronavirus restrictions during the fourth quarter and the wave of infections following the sudden, almost complete lifting of restrictions in December 2022. Zero growth is exceptional for China. Ever since this time series started back in 1992 we have only seen lower values in the first quarter of 2020 and the second quarter of 2022, which were due to coronavirus restrictions in place at the time. The level of GDP in Russia is also noteworthy. After falling sharply in the second quarter of 2022 it unexpectedly achieved slightly above-average growth in the third quarter. One possible explanation for this is that the conversion of the economy to war production is stimulating GDP. However, these figures are doubted by some experts.

Inflation continues to decline

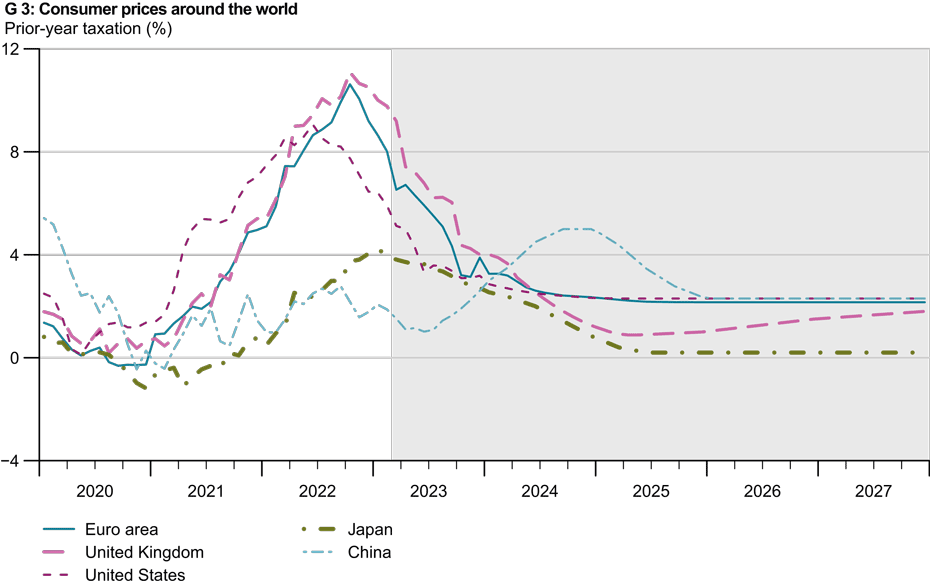

As expected, the rate of increase in consumer prices in the United States, Europe and Japan has continued to slow in recent months (see chart G 3 entitled ‘Consumer prices around the world’). The reason for this has been the decline in energy prices and the decrease in price growth as a result of the weaker economy. This trend is also reflected in the fact that producer prices in various countries have been falling or stagnating for several months now. Germany’s cap on electricity and gas prices is also likely to have had a moderating effect on inflation. However, inflation remains high in many places (January’s figures: 6.4 per cent in the US, 9.2 per cent in Germany, 7.0 per cent in France, 10.7 per cent in Italy, 8.6 per cent in the euro area, 10.0 per cent in the UK and 4.3 per cent in Japan) and is broad-based.

Reducing the pace of monetary tightening

The US Federal Reserve (Fed), the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of England (BoE) have tightened the monetary reins further in recent months. The target range for the federal funds rate is currently 4.75 to 5.00 per cent (increase of 25 basis points in the second half of March). And the ECB’s marginal lending facility rate is currently 3.75 per cent (recently increased by 50 basis points). KOF expects central banks to continue raising interest rates until the summer of 2023, albeit somewhat less ambitiously than before. Bond programmes are also likely to be scaled back further, which tends to put upward pressure on medium to longer-term interest rates.

One of the reasons for continuing to tighten monetary policy despite falling inflation rates is that the labour market remains very tight in many places and significant wage increases can be expected in the future. Production capacity utilisation also remains high in some places, putting pressure on prices. By tightening monetary policy, central banks aim to curb multi-round effects on inflation and prevent any stabilisation of inflation dynamics. Another reason for continuing to tighten policy is that any economic scarring has so far been less than expected. KOF expects to see no further or only modest interest-rate hikes from the summer of 2023 onwards, although the scaling-back of bond programmes is likely to continue if the economy is buoyant. If the economy deteriorates noticeably (see risks on the next page), monetary tightening is likely to end or at least be less pronounced.

Inflation likely to fall and global output to remain below average for now

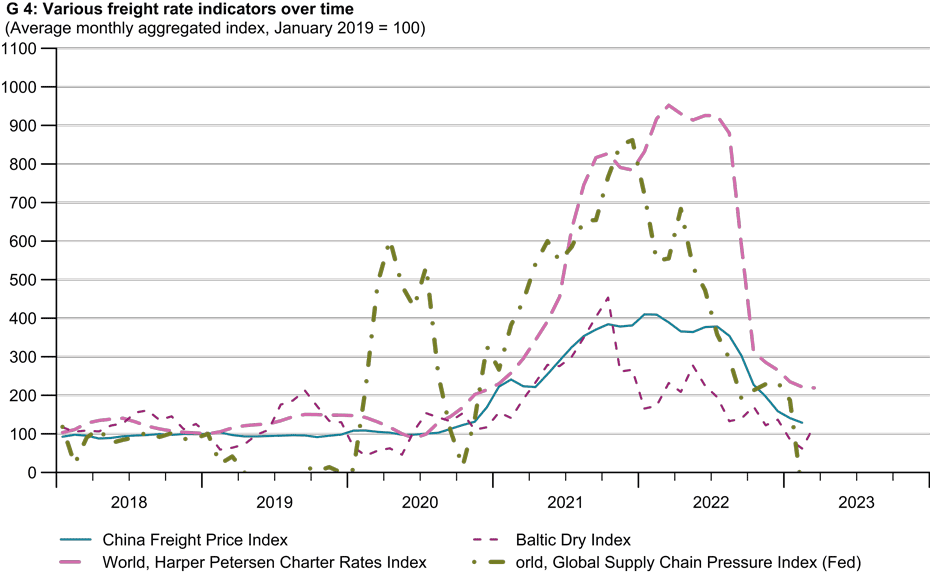

As base effects disappear, inflation is likely to fall significantly in many countries over the coming months (see chart G3 entitled ‘Consumer prices around the world’). But even after inflation declines in the first half of 2023, it is likely to remain above central banks’ targets in many countries. For example, KOF is forecasting annual inflation of 5.6 per cent for the euro area in 2023 and 2.7 per cent for 2024, while annual inflation rates of 4.1 per cent in 2023 and 2.5 per cent in 2024 are expected for the US. Inflation in China is expected to rise this year as a result of its anticipated recovery following the lifting of COVID-19 restrictions. However, this increase will be less pronounced than the recent rises in the US and Europe as supply chain problems have continued to ease (see chart G4 entitled ‘Various freight rate indicators over time’) and as the link between producer and consumer prices seems to be weaker in China than in other countries.

The broad-based recovery of economic indicators in recent months suggests that European economies will probably not stagnate in the first half of 2023. However, output in some European countries is likely to be below average. This is because the energy crisis and monetary tightening are still constraining economic activity. KOF expects to see weak GDP growth in the US during the first half of the year, as consumption growth rates are likely to decline. Until recently, however, its Nowcasting Lab was indicating strong GDP growth there (see external pagehttps://nowcastinglab.org).

A massive consumption recovery is expected in China in the first half of the year following the lifting of its COVID-19 restrictions and the abatement of the ensuing wave of infections. The global economy should also benefit from this. KOF is forecasting a 1.4 per cent increase in Swiss-export-weighted world GDP for 2023 as a whole. Growth of 2.1 per cent is expected for 2024. This represents a significant upward revision compared with its winter forecast (0.5 per cent for 2023 and 1.9 per cent for 2024).

Multiple risks

This forecast was prepared under the technical assumption that the oil price and other energy prices would increase only slightly (1.5 per cent per year) over the forecast horizon. The current uncertainty about energy prices also makes the economic outlook and, especially, the inflation outlook uncertain. Furthermore, this forecast is subject to a number of risks. Downside risks include any stronger-than-expected adverse effect of increasingly restrictive monetary policy, the possibility of a renewed deterioration of the real-estate crisis in China, and any further escalation of geopolitical tensions arising from the war in Ukraine and the conflicts between the US and China.

The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (which occurred after this forecast was prepared), the problems at other US banks and UBS’s takeover of Credit Suisse also highlight the risk of a new financial crisis. Given the repeal and non-observance of risk-mitigating regulation in recent years, parts of the financial system now appear to be less robust than they were before the global financial crisis of 2007 to 2009.

Upside risks are that the mitigation of supply chain problems could unleash stronger-than-expected momentum in 2023. At the very least, the risk of recurrent production shutdowns and port closures in China disrupting international supply chains has fallen dramatically. In addition, the GDP stimulus resulting from the energy transition in Europe may have been underestimated in the forecast. Furthermore, there is a possibility that the current geopolitical conflicts will perpetuate and thus cease to be considered by economic actors, which would boost investment and consumption.

Contacts

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

KOF FB Konjunktur

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

KOF FB Konjunktur

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland