Why has Switzerland, unlike Germany, not developed a large low-wage sector? An overview

In Switzerland – in contrast to Germany – low wages have managed to keep up surprisingly well with average wages. Research to date cannot conclusively explain the different trends in these two countries. In this article, KOF economist Kristina Schüpbach discusses various theories on this topic. One possible explanation is that Switzerland’s job market is more extensively covered by collective labour agreements than Germany’s.

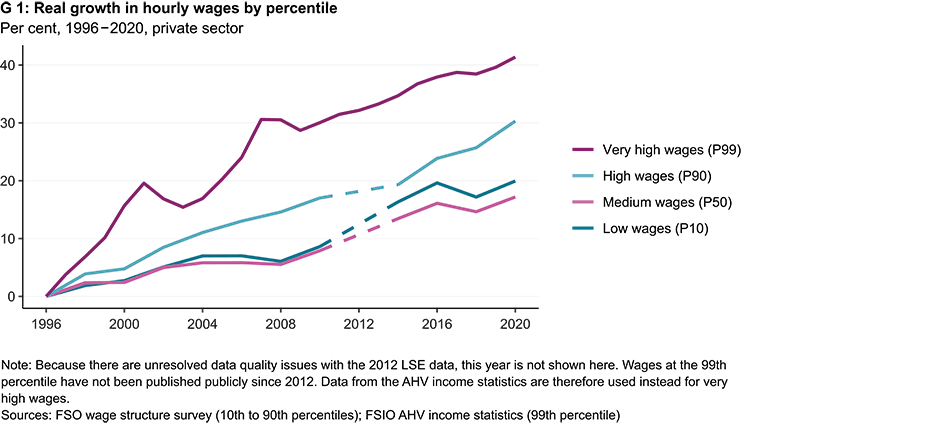

Although wage inequality in Switzerland is significantly higher today than it was in the mid-1990s, the size of its low-wage sector has hardly changed. Measured against the total number of jobs offered by companies, the share of low-wage jobs has remained between 10 and 11.5 per cent over the last 30 years. Wage inequality increased in the late 1990s and up to the financial crisis – especially towards the top end of the range. Low wages (10th percentile limit, 10 per cent of workers earn less), on the other hand, have always managed to keep up with average wages (median wage, 50 per cent earn less) (see chart 1).

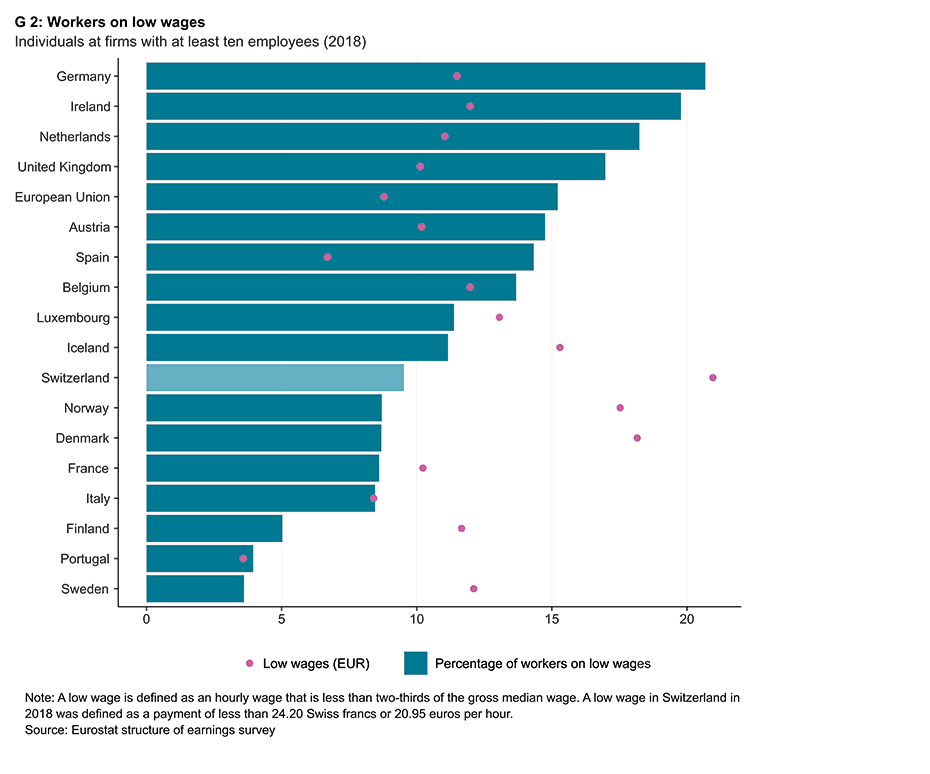

The relative stability of low wages is notable. In Germany, low wages fell by over 20 per cent in real terms at the beginning of the noughties. At the same time, the share of workers on low wages increased by almost half (Grabka and Schröder 2019). A low wage is defined as hourly pay that is less than two-thirds of the gross median wage. In contrast to Germany, no significant low-wage sector has emerged in Switzerland, with the ratio of low to average wages remaining surprisingly constant. It is also interesting to note that labour force participation in Switzerland has remained consistently high. Many economists argue that wage inequality increases as unemployment declines. This is because if the labour market participation rate of fairly low-skilled individuals rises, it is plausible that the low-wage sector will grow. According to this logic, Germany has achieved higher (low-wage) employment and lower unemployment at the cost of greater wage inequality. Switzerland’s experience suggests that low unemployment does not necessarily involve high wage inequality and a large low-wage sector. Compared with other western European countries, Switzerland is slightly below average in terms of the proportion of those on low wages (see chart 2). The Nordic countries as well as France, Italy and Portugal have lower proportions of low-wage jobs. Germany, the United Kingdom and other central European countries, on the other hand, have significantly larger low-wage sectors.

The usual explanations are unlikely to explain the different trends

Why has a large low-wage sector emerged in certain countries such as Germany and the UK, while the proportion of low-wage jobs has remained comparatively low in Switzerland and other western European countries? Various theories have been explored in the economic literature to explain the growing wage inequality in many countries. The most common explanation is that technological change – or, more specifically, digitalisation and automation – has increased employers’ demand for highly skilled labour. Because the number of skilled workers has not grown at the same rate, the wages of individuals with a university degree have increased compared to those with an intermediate level of education. In Switzerland, these are people with a vocational apprenticeship or Matura (school-leaving certificate). The automation of routine activities has also reduced the need for workers with an intermediate level of education in some occupations, such as production and administration (Antonczyk, DeLeire and Fitzenberger 2018; Acemoglu and Autor 2011).

A study of the situation in Switzerland addressed this thesis. In regions whose industries were more geared towards routine activities than in other regions, more was invested in automation, the immigration and employment of high-skilled workers rose more significantly, and the wage gap between high-skilled and medium-skilled workers increased. Consequently, technological change seems to play a relevant role in the stronger growth of high wages. In contrast, according to the study, it did not lead to an increase in the employment of low-skilled workers nor to any growth in wage inequality in the lower half of the distribution (Beerli, Indergand and Kunz 2023).

The study examined various other factors around globalisation, such as increasing worldwide competition, the outsourcing of production to low-wage countries, growing productivity differences between international and local firms, and the acceleration of technological change due to greater global networking. Although all of these factors tended to increase inequality, there is some disagreement about the relative importance of the individual points (see OECD 2011 for an overview). However, the different trends observed across western European countries can hardly be explained by technological change and globalisation alone. There is no evidence to suggest that Switzerland has been less affected by either factor than other countries, nor is this to be expected a priori.

Accompanying measures have raised the CLA coverage rate

Institutional factors could also play an important role. One such factor is the design and development of labour market institutions, such as collective wage bargaining and government-imposed minimum wages. In Switzerland, coverage by collective labour agreements (the proportion of workers covered by a collective labour agreement (CLA)) increased from 38 per cent to 49 per cent between 2001 and 2012 (State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO) 2013). In Germany and the UK, on the other hand, CLA coverage fell significantly, while it remained stable in most other western European countries (OECD 2019).

One possible factor shaping the trend in Switzerland has been the measures accompanying an agreement with the EU concerning the free movement of individuals (FlaM), which was introduced in 2004. These measures were intended to mitigate the wage pressures feared and to prevent some employers from taking advantage of immigration and engaging in wage dumping. Specifically, the FlaM lowered the barriers to declaring a CLA negotiated between trade unions and industry associations binding for all companies in the sector concerned. According to the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs, the degree of coverage by such generally binding collective labour agreements doubled from 12 per cent to 24 per cent between 2001 and 2012. In addition, the trade unions have been able to establish themselves in service industries with traditionally low wages and to conclude new collective labour agreements in sectors such as cleaning and security services.

Has collective wage bargaining prevented low wages from falling?

Various studies on other countries show that collective wage bargaining mitigates wage inequality by raising low wages and reducing high wages (Lucifora, McKnight and Salverda 2005; OECD 2019). The more sectors and occupations that have to comply with such agreements, the greater the dampening effect that collective wage bargaining has on wage inequality. Coordination of wage demands and negotiations at the national level also help to prevent the emergence of large sectoral differences.

Several studies on Germany conclude that the shift in wage bargaining from industry level to firm level and the general decrease in coverage by collective agreements can explain the drop in low wages there (see, for example, Antonczyk, DeLeire and Fitzenberger 2018; Card, Heining and Kline 2013). Conversely, the introduction of the national minimum wage in Germany in 2015 raised the lowest wages and thus slightly reduced wage inequality (Grabka and Schröder 2019).

The effect that collective agreements have on wage inequality in Switzerland, on the other hand, has not yet been studied. One reason for this may be that there has so far been no systematic recording of the most important contractual features – especially the level of minimum wages. Evidence from other countries suggests that collective agreements have helped to stabilise wage inequality at the lower end of the distribution over the last twenty years.

In addition to collective agreements, other factors could be relevant for the comparatively small low-wage sector in Switzerland. The close alignment of the country’s vocational training system with its labour market and the opportunities available for continuing professional development may have contributed to the fact that people without a university degree have also been able to keep up with technological change. This would then be one reason why certain technologies have spread in Switzerland in a similar way to other countries but have not had the same effect. The generous level of unemployment benefits compared with other countries may also have played a role here. A good system of social security means that workers are under less pressure to accept any job and any wage. However, higher labour costs can also reduce demand from industry. Nonetheless, there is generally mixed evidence on the impact that the level of unemployment benefits has on starting wages (see, for example, Jäger et al. 2020; Dahl and Knepper 2022). It is also conceivable that the public debate surrounding the initiative for a national minimum wage – although it failed at the ballot box in 2014 – has set a kind of lower limit on what level of wage is considered socially acceptable.

Further research is needed

The different evolution of the low-wage sectors in Switzerland and Germany is in need of explanation. While research to date provides a few explanatory approaches, many questions remain unanswered. In particular, there is a lack of research on the impact that collective agreements have on (low) wages and employment in Switzerland.

Contact

KOF FB Arbeitsmarktökonomie

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

Literatur

Acemoglu, Daron, and David Autor (2011): external pageSkills, Tasks and Technologies: Implications for Employment and Earnings. In Handbook of Labor Economics, 4:1043–1171. Elsevier.

Antonczyk, Dirk, Thomas DeLeire, and Bernd Fitzenberger (2018): external pagePolarization and Rising Wage Inequality: Comparing the U.S. and Germany. Econometrics 6 (2): 20.

Beerli, Andreas, Ronald Indergand, and Johannes S. Kunz (2023): external pageThe Supply of Foreign Talent: How Skill-Biased Technology Drives the Location Choice and Skills of New Immigrants. Journal of Population Economics 36 (2): 681–718.

Card, David, Jörg Heining, and Patrick Kline (2013): external pageWorkplace Heterogeneity and the Rise of West German Wage Inequality. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 128 (3): 967–1015.

Dahl, Gordon and Matthew Knepper (2022): external pageUnemployment Insurance, Starting Salaries, and Jobs. NBER Working Paper No. 30152.

Grabka, Markus M., and Carsten Schröder (2019): external pageThe Low-Wage Sector in Germany Is Larger than Previously Assumed. DIW Weekly Report 14 (April): 118–25.

Jäger, Simon, Benjamin Schoefer, Samuel Young, and Josef Zweimüller (2020): external pageWages and the Value of Nonemployment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 135 (4): 1905–63.

Lucifora, Claudio, Abigail McKnight, and Wiemer Salverda (2005): external pageLow-Wage Employment in Europe: A Review of the Evidence. Socio-Economic Review 3 (2): 259–92.

OECD. 2011. external pageDivided We Stand: Why Inequality Keeps Rising. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. 2019. external pageNegotiating Our Way Up. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Staatssekretariat für Wirtschaft (SECO) (2013): external pageTieflöhne in der Schweiz und Alternativen zur Mindestlohn-Initiative im Bereich der Voraussetzungen für die Allgemeinverbindlicherklärung von Gesamtarbeitsverträgen und für den Erlass von Normalarbeitsverträgen. Bern.