“Inflation will remain high by Swiss standards in 2023”

KOF expects interest rates to continue to rise this year in the euro area, the United States and Switzerland. It predicts that inflation will eventually fall but will remain high. The two economists Alexander Rathke and Pascal Seiler explain why in an interview.

The US Federal Reserve (Fed), the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Swiss National Bank (SNB) all raised their key interest rates by 0.5 percentage points at the end of last year. The Bank of England and the Bank of Japan also recently tightened their monetary policies. Were these rate hikes coordinated? Are the other central banks following the Fed’s lead or does this merely reflect their respective needs?

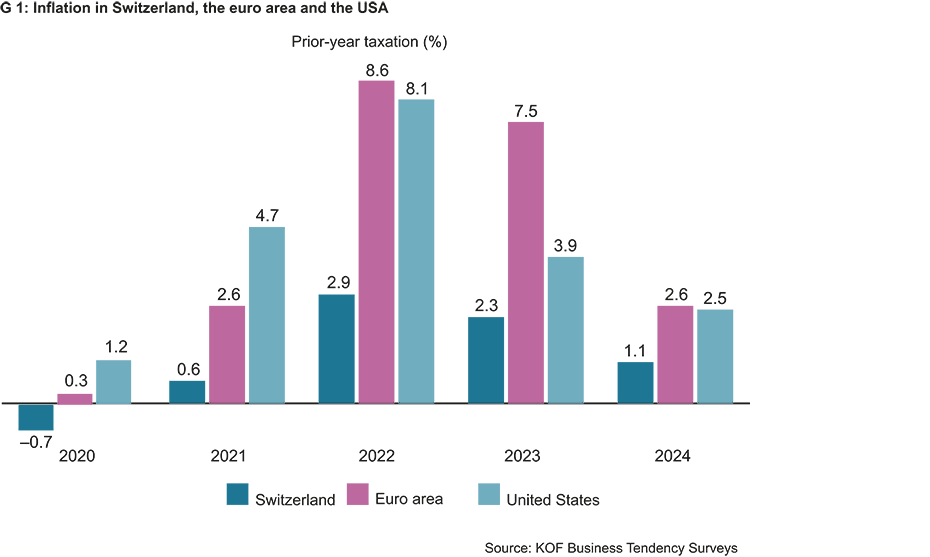

Seiler: These uniform increases across the various currency areas should not obscure the different macroeconomic situations and interest-rate cycles in which these economies find themselves. In the United States, the Fed started raising interest rates relatively early. In Europe, the ECB hiked its key interest rates much later than its American counterpart. In Switzerland, on the other hand, inflation has never been anywhere near as high as it is in the US and the euro area. The SNB is therefore starting from a different position than the Fed and the ECB are.

Rathke: The problem in these three currency areas is fundamentally the same: central banks are having to raise interest rates because inflation is too high. However, the reasons for this high inflation are not the same everywhere. In the US, for example, the energy aspect is less important than it is in Europe. On the other hand, there is an extreme shortage of workers in the American labour market. The number of job vacancies is three million higher than it was before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. This is translating into high wage growth and surging service prices. In Europe, on the other hand, the prices of goods are currently still rising.

“The problem in these three currency areas is fundamentally the same: central banks are having to raise interest rates because inflation is too high.”Alexander Rathke, KOF Economist

The relevant key interest rates are now 1 per cent in Switzerland, 2.5 per cent in the euro area and between 4.25 and 4.5 per cent in the United States. Does this mean that we have already achieved a neutral interest rate, i.e. a monetary policy that is neither restrictive nor expansionary?

Rathke: The concept of a neutral interest rate is complex and controversial. Basically, we can say that monetary policy is less expansionary than it was before. But whether we are already in neutral territory is difficult to say.

Seiler: When central banks started raising their key interest rates, speed was of the essence. These hikes have recently become smaller again and, in the near future, we will probably no longer see huge rises of 0.75 percentage points. The US Federal Reserve is likely to be the first to enter the next phase of monetary policy. More important than speed will then be the question of how far interest rates have to rise and how long they have to stay there. Central banks will probably try to approach this level slowly and gradually, carefully examining the cumulative effects of their previous monetary tightening and any time lag.

How long will interest rates continue to rise?

Seiler: At KOF we reckon that interest rates will continue to rise until mid-2023, which is when the federal funds rate will peak. The ECB will raise rates even more than financial markets have anticipated thus far. The SNB will also continue with its hikes, although it will restore part of the traditional interest-rate differential. However, we do not expect to see any interest-rate cuts – which have already been speculated about in financial markets – before the forecast horizon at the end of 2024.

Central banks’ balance sheets expanded massively during the financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. What progress are central banks making in reducing their balance sheets?

Rathke: The US Federal Reserve has been shrinking its balance sheet for some time. The ECB plans to gradually start reducing its bond holdings in March. The SNB currently has no explicit balance sheet reduction targets. Its large volume of total assets is a by-product of its past exchange-rate policies, when it bought foreign currencies to weaken the Swiss franc. The SNB has now sold foreign currency in recent months, which will shrink its balance sheet.

“We predict that the franc will continue to appreciate nominally this year.”Pascal Seiler, KOF Economist

How does KOF expect the Swiss franc’s exchange rate to evolve over time?

Seiler: We predict that the franc will continue to appreciate nominally this year. The main arguments for this assessment are the inflation differential with other currency areas and the SNB’s interest in maintaining a strong franc to keep imported inflation in check.

How high will inflation in Switzerland be this year and next?

Seiler: Inflation is likely to be shaped by various countervailing effects this year. On the one hand, potential second-round effects and the increase in administered prices (e.g. electricity) at the beginning of the year could further fuel inflation. There is also a risk that a more restrictive monetary policy could cause rents to rise in the medium term. On the other hand, expiring base effects in energy prices, the subsiding disruption to international supply chains and a further appreciation of the Swiss franc should reduce inflationary pressures. Overall, we expect inflation in Switzerland to be 2.3 per cent this year and 1.1 per cent next year. We are also forecasting lower inflation for the euro area and the US (see chart G1). Even at the end of the forecast horizon in 2024, however, these rates should still be above the respective inflation targets.

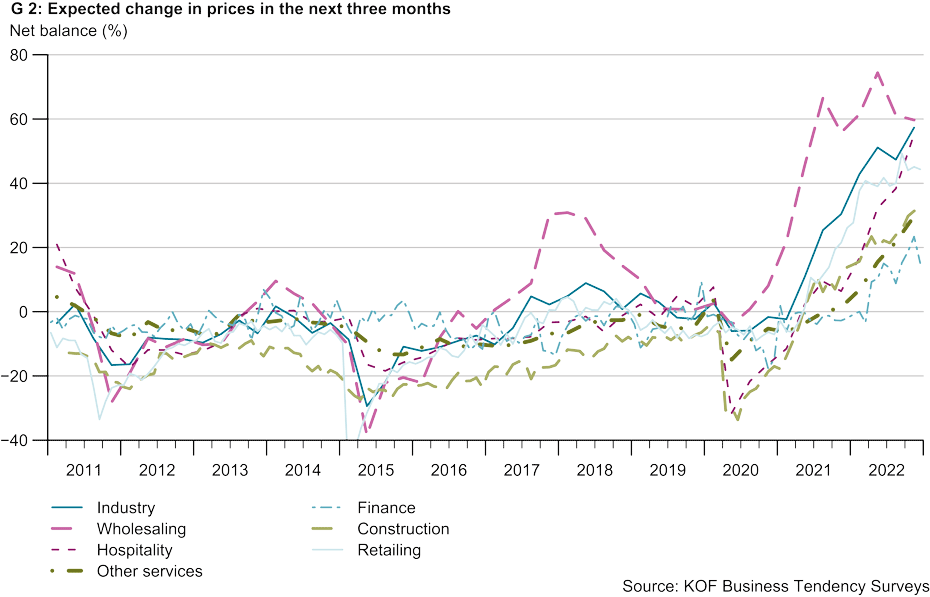

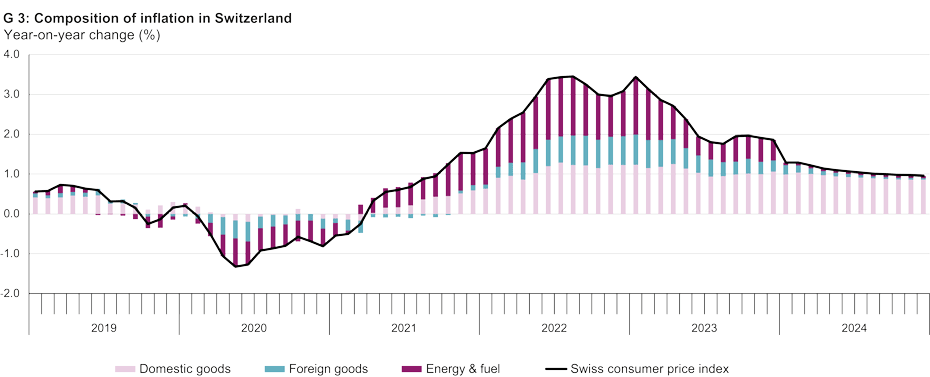

Rathke: KOF’s Business Tendency Surveys reveal that many companies are looking to raise their prices this year in order to pass on their higher production costs to consumers (see chart G2). Consequently, inflation is broadening out (see chart G3). It now consists not only of energy price rises and some goods that were particularly affected by the pandemic. Inflation will therefore remain relatively high this year by Swiss standards.

Is there a danger of a wage-price spiral in Switzerland?

Rathke: Not at the moment. If wages are compensating for a loss of purchasing power in the past, that is not necessarily a wage-price spiral. It only becomes a spiral if wages and prices are pushing each other up because the expected inflation is anticipated in advance in the form of excessive wage demands. This is not happening in Switzerland at present.

There are several megatrends – such as demographic change, deglobalisation and the fight against climate change – that tend to fuel inflation. Wouldn’t it therefore make sense to raise central banks’ inflation target from the current 2 per cent to 3 per cent?

Rathke: Basically, such a move was considered in the wake of the financial crisis. The idea was that this would lower the probability that interest rates would hit their effective lower limit. But now is absolutely the wrong time for such a debate because that would make central banks untrustworthy in the fight against inflation.

KOF’s latest economic forecast is available external pagehere.

Contacts

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

KOF FB Konjunkturumfragen

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

KOF Bereich Zentrale Dienste

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland