How do firms determine their prices?

New survey data provide insights into the price-setting behaviour of Swiss companies. They shed light on price setters’ motives when they are reviewing, forming and adjusting their prices, as well as the reasons why they do not adjust their prices. In particular, they illustrate how prices are set so as to take account of the competing interests between customers and competitors.

How firms determine their prices is of great macroeconomic importance for at least two reasons. First, price indices are weighted sums of individual prices. Individual decisions on price adjustments therefore have a direct impact on inflation as a whole. Second, price setting determines the way in which economic shocks affect the economy as a whole. To the extent that prices do not respond directly or only imperfectly to changes in supply and demand, monetary stimuli have an impact on real economic activity. For these reasons it is important for both research and monetary policy to understand how prices are set and what factors influence price adjustment.

Accordingly, extensive empirical research in recent decades has shed light on the extent and causes of sluggish price adjustment and deepened our understanding of firms’ price-setting behaviour.1 This research is largely based on quantitative price data. However, research based on quantitative data is often blind to factors such as price setters’ expectations, considerations and motivations underlying their price-setting behaviour. Moreover, quantitative data only provide information on the actual decisions made by firms but do not shed light on the other stages of the pricing process.

An ad-hoc survey sheds new light on pricing

In order to shed light on these otherwise invisible factors and phases of price setting, an ad-hoc survey of Swiss companies was conducted as part of an ongoing research project, and qualitative insights into their price setting were obtained (Seiler, 2022a, b). The phases considered include reviewing, forming and adjusting prices as well as the reasons for not adjusting prices.

The survey was conducted in the spring of 2022 among private Swiss firms that regularly participate in the KOF Investment Survey. A total of 5,551 companies were contacted, of which 1,555 responded. In addition to manufacturing the sample also includes a large number of firms from the retail sector and other service industries, which allows reliable conclusions to be drawn not only about producer prices but also about consumer prices.

Prices are reviewed on various occasions and more often than they are actually changed

Firms review their prices on various occasions: prices are reviewed both at regular intervals (‘time-dependent pricing’) and in response to specific events (‘state-dependent pricing’).

The average firm reviews its prices twice a year and changes them annually. However, these frequencies vary considerably between sectors. The median retail company changes its prices quarterly, industrial firms half-yearly and other service providers once a year or less. These review and adjustment frequencies are higher among companies that generate a larger share of their turnover from the internet or that face more intense competition. In addition, according to their own assessments, companies are adjusting their prices more frequently today than they did five years ago and they expect this trend to continue in the future.

All of these may be signs of increased competition as a result of the emergence of online retailing. In fact, digital technologies have also found their way into pricing. 14 per cent of firms compare their prices with those of their competitors in an automated form. 28 per cent of companies calculate their prices automatically. In all likelihood these are algorithms that calculate sales prices based on purchase prices, other costs and a target profit margin. Finally, more than one tenth of firms decide to change their prices without any human interaction.

Prices are based on competitors’ prices and are highly differentiated

About half of all companies pursue an independent pricing policy and determine the prices of their products and services themselves. Pricing for many firms in the manufacturing sector is also influenced by negotiations and contracts with customers. Conversely, negotiations with suppliers play an important role in the retail sector.

When setting their prices, firms most often take account of information on the current behaviour of all of the variables relevant to pricing. In addition, information about the past and expected future behaviour of those variables plays a minor role. Most firms set their prices in response to their competitors’ prices. Price mark-up rules, where companies add a fixed or variable percentage to their calculated unit costs, accurately describe the price calculation process in trade and industry but have become less important compared with previous national (Zurlinden, 2007) and international surveys (Blinder, 1998; Fabiani et al., 2005).

The survey’s findings clearly reject the notion of uniform pricing: companies differentiate their prices along various dimensions. 66 per cent of them vary their prices depending on the quantities sold. 61 per cent pursue a personalised pricing strategy and differentiate their prices between customers. Half of them vary their prices regionally within Switzerland. One fifth of them adjust their prices in real time to market dynamics or the time of day (‘dynamic pricing’). In addition, 13 per cent of firms differentiate their prices by sales channel (online vs. offline).

Price adjustments are made asymmetrically in response to changes in costs and market conditions

Are price changes synchronised within or between firms? Synchronisation within companies measures the extent to which firms coordinate price changes across their entire product range. Inter-company synchronisation measures the extent to which firms change their prices at the same time as their competitors. Between a quarter and a third of businesses report synchronised price changes, with synchronisation within firms outweighing synchronisation between them. The likelihood of price changes is slightly higher if prices have not changed for a long time than if they have changed recently. This indicates a flat but, overall, slightly increasing age failure rate (‘duration hazard function’).

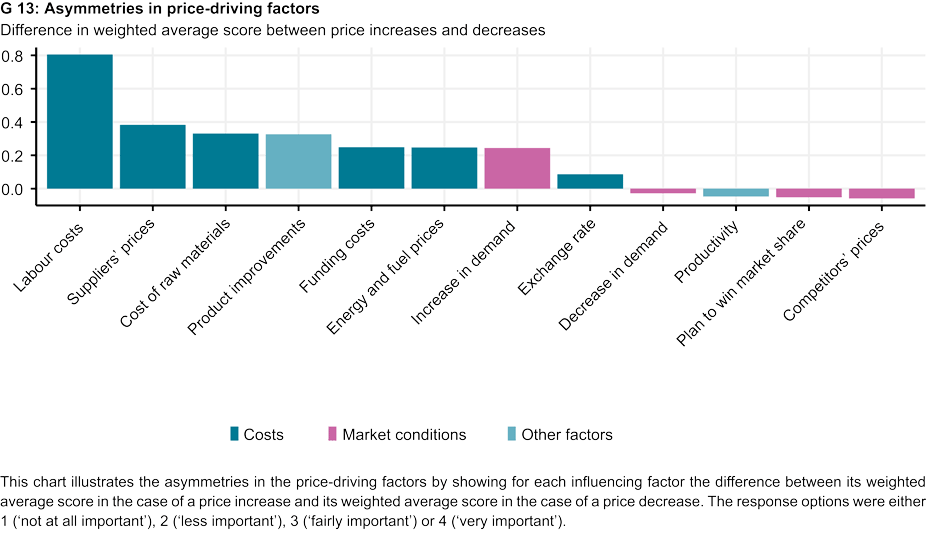

Labour costs, raw-material costs and supplier prices are among the most important factors motivating price changes. Changes in these factors have the greatest impact on sales prices and influence them asymmetrically. Chart G 13 shows for each influencing factor the difference between its mean importance for a price increase and its mean importance for a price decrease. The results show a strikingly regular pattern of positive asymmetries for cost factors and negative asymmetries for factors affecting market conditions. Higher costs are more relevant to price increases than lower costs are to price decreases. Conversely, shocks to market conditions (e.g. lower prices set by competitors) are more important for price reductions than for price increases.

Concern for customer relationships shapes price rigidities

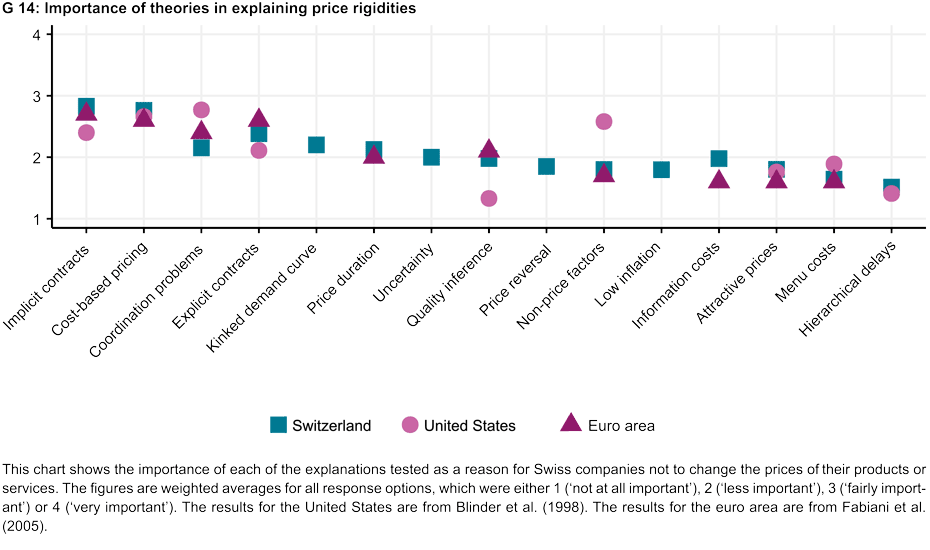

The most commonly cited reason for not adjusting prices is implicit contracts with customers (see chart 13). According to the theory of implicit contracts, companies aim to build long-term customer relationships and retain their clients by keeping prices as stable as possible. Changing prices more frequently could affect these relationships. Concern for their customer relationships accordingly plays a key role in firms’ pricing behaviour. Constant costs as well as fixed contracts that limit the ability to change prices are other important reasons why companies do not adjust their prices more frequently. Relatively insignificant are the costs associated with price adjustments. This concerns both the information costs (these are, for example, the time and effort required to obtain all of the information needed for price decisions) and the physical costs of price changes (e.g. the printing of new catalogues or the replacement of price tags). The fact that such ‘menu costs’ do not seem to play a significant role is remarkable insofar as menu costs are a popular means of modelling nominal price rigidities in the literature.

When companies are asked to assess the importance of the same theories for their price setting since the pandemic, it becomes apparent that all theories explaining price rigidities have become less important. This is consistent with the picture of recent fundamentally more flexible pricing behaviour and the recent rise in inflation. However, not all theories have lost importance equally. Cost-based pricing rules and implicit contracts in particular have played a lesser role in preventing price changes since the pandemic. Firms seem more willing to pass on higher costs to their prices than before the pandemic. Additionally, they seem less concerned with stable prices than before the pandemic in order not to harm their customer relationships. One possible explanation for this survey result could be fairness considerations (Rotemberg, 2005). Customers are more likely to accept higher prices due to exogenous factors (e.g. pandemic or war) and cost factors (e.g. purchase prices or energy costs) than higher prices as a result of increased demand.

1 These quantitative price data include the increasingly available micro data underlying consumer and producer price indices, and alternative price data sets such as scanner data or prices collected on the internet by means of ‘web scraping’. Klenow and Malin (2010) and Nakamura and Steinsson (2013) provide a comprehensive overview of micro-pricing studies and summarise the microeconomic evidence available on price-setting behaviour. Rudolf and Seiler (2022) provide recent evidence of consumer prices in Switzerland.

---------------------------------------------

References

Blinder, A., E. R. Canetti, D. E. Lebow, and J. B. Rudd (1998): Asking about prices: A new approach to understanding price stickiness. Russell Sage Foundation.

Fabiani, S., M. Druant, I. Hernando, C. Kwapil, B. Landau, C. Loupias, F. Martins, T. Mathä, R. Sabbatini, H. Stahl, and A. C. Stockman (2005): The pricing behaviour of firms in the euro area: New survey evidence. ECB Working Paper Nr. 535.

Klenow, P. J. and B. A. Malin (2010): Microeconomic evidence on price-setting. In Handbook of Monetary Economics, volume 3, pages 231–284. Elsevier.

Nakamura, E. and J. Steinsson (2013): Price rigidity: Microeconomic evidence and macroeconomic implications. Annual Review of Economics, 5(1):133–163.

Rudolf, B. and P. Seiler (2022): Price Setting Before and During the Pandemic: Evidence from Swiss Consumer Prices. ECB Working Paper Nr. 2748.

Rotemberg, J. J. (2005): Customer anger at price increases, changes in the frequency of price adjustment and monetary policy. Journal of Monetary Economics, 52(4):829–852.

Seiler, P. (2022b): How do Companies Set Their Prices? Survey Evidence From Switzerland. Mimeo.

Zurlinden, M. (2007): The pricing behaviour of Swiss companies: Results of a survey conducted by the SNB delegates for regional economic relations. Swiss National Bank Quarterly Bulletin, 1.

A detailed analysis of the price-setting behaviour of Swiss companies can be found in the external pagecurrent KOF analyses: Seiler, P. (2022a): How do companies determine their prices? Results of an ad hoc survey in Switzerland. KOF Analyses, Vol. 2022(4), pp. 28-62.

Contact

KOF FB Konjunkturumfragen

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland