Monetary policy: provisional end to negative interest rates

Central banks in Switzerland, the euro area and the United States are raising interest rates swiftly. In the long term, however, KOF expects to see lower rates return.

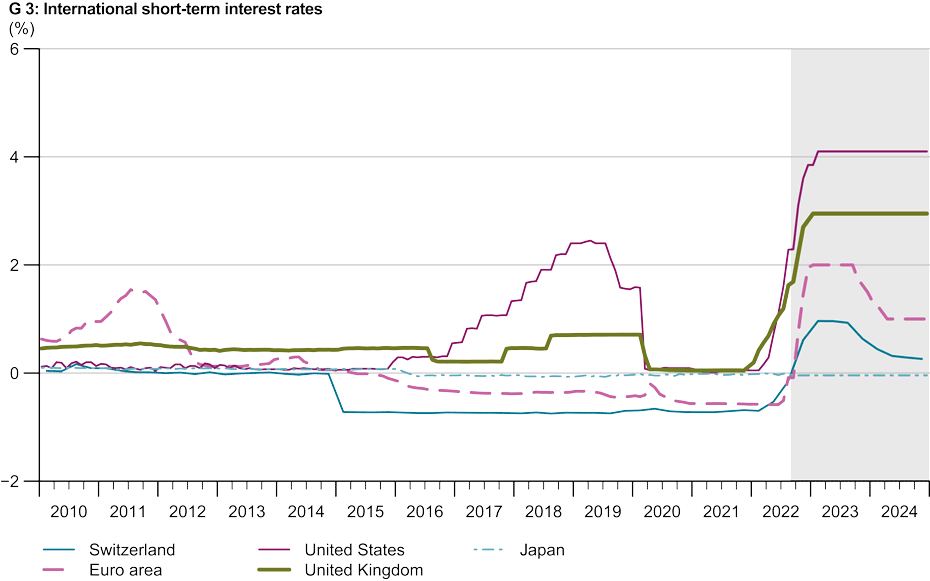

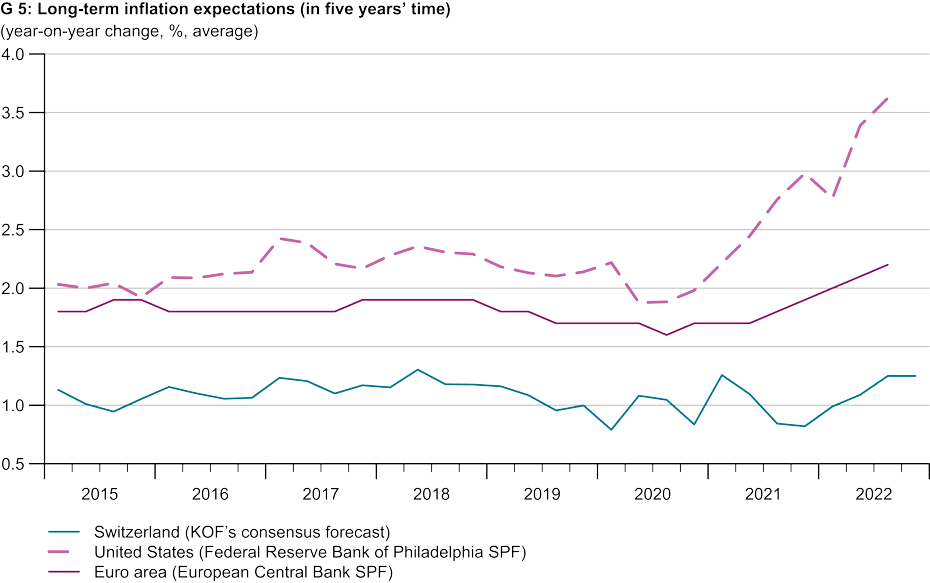

Monetary policy normalisation in the major currency areas continues to accelerate. The underlying driver is the trends in consumer prices and long-term inflation expectations, both of which have picked up significantly recently. By the time the forecast horizon in 2024 is reached, inflation rates in the US and the euro area are expected to have returned to around 2 per cent, which will bring central banks’ tightening efforts to an end. Compared with previous years, the medium-term equilibrium is thus characterised by a generally higher level of interest rates (see chart G 3).

Fed tightens interest rates significantly

The US Federal Reserve (Fed) raised key interest rates by 75 basis points at its September meeting, as it had done in June and July. The target range for its key interest rate is thus currently 3 to 3.25 per cent. The last time interest rates were in this range was before the outbreak of the financial crisis about 15 years ago, which underlines the fact that the low-interest-rate environment is over for the time being. The reason for tightening monetary policy is persistently high American inflation, with consumer prices rising by more than 8 per cent year on year in August. However, this is not only due to the energy and food markets being affected by the war in Ukraine, as core inflation – at over 6 per cent year on year – is also well above the Fed’s target of 2 per cent. The Fed is therefore under pressure to contain future price rises precisely because of the overheating labour market.

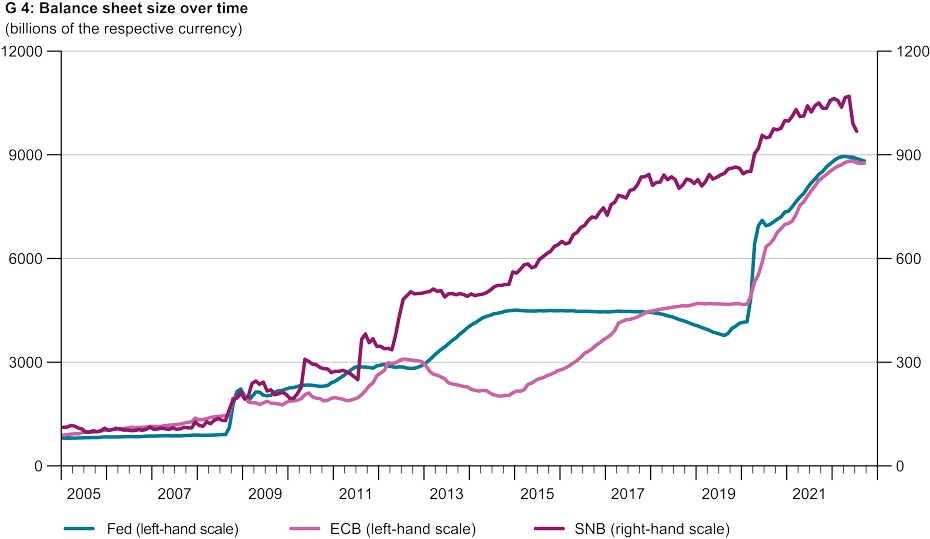

KOF expects to see a further tightening of interest rates in the US currency area over the coming months. By the end of the first quarter of 2023, key interest rates should be within a target range of 4 to 4.25 per cent, where they will remain until the end of the forecast horizon. The prerequisite for this is a steady flattening of inflation, which should be slightly above 2 per cent and thus close to its target in 2024. Apart from the level of interest rates, tighter monetary policy is also gradually making itself felt on the balance sheet (see chart G 4). After having grown significantly during the pandemic, the size of the balance sheet has been gradually decreasing since April of this year. This trend is likely to continue as a key plank of monetary policy over the coming years.

ECB restrictive only in the medium term

The European Central Bank (ECB) is also tightening the monetary reins. After its key interest rates were raised by 0.5 per cent in July, a historic jump of a further 75 basis points followed at its September meeting. After years of negative interest rates, the deposit rate is currently 0.75 per cent. The ECB’s policy is a response to persistently high inflation in the euro area, which has been hit harder by the effects of the war in Ukraine than the US has. Consumer prices in August rose by 9.1 per cent year on year, which is the highest level measured since the introduction of the euro. This was due to higher energy (up 38.3 per cent) and food (up 10.6 per cent) prices, which together pushed up inflation by almost six percentage points.

Since consumer price inflation in the euro area is not expected to fall below 8 per cent by the end of the current year and will actually rise slightly, further interest-rate hikes are expected here. Specifically, the ECB’s Governing Council is likely to raise the deposit rate to 2 per cent at its October and December meetings. These decisions will be supported by the new Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI), which is intended to counteract wide spreads in the bond markets. This is to ensure that the funding conditions for fiscally weaker countries do not become excessively tight. This more restrictive monetary policy is reflected in the size of the ECB’s balance sheet to the extent that it has stagnated – in contrast to the past two years. Nevertheless, it is expected that key interest rates will be lowered again as inflation flattens from mid-2023 onwards in response to the sluggish economy in the euro area, which is characterised by real-terms losses of purchasing power and precautionary saving.

An end to Switzerland’s negative interest rates

The monetary policy tightening taking place in the major currency areas is also leaving its mark on Switzerland. The Swiss National Bank (SNB) raised key interest rates for the first time in 15 years at its June meeting. This was followed by a further tightening of 75 basis points in September, bringing the current key interest rate to 0.5 per cent. After more than seven years of negative interest rates in Switzerland, banks are now finally receiving money on their deposit accounts at the SNB. Here, too, the rise in interest rates can be explained by higher inflation. Although this is comparatively low at just over 3 per cent (consumer price inflation) and 2 per cent (core inflation), the percentage increase in consumer prices is above the SNB’s target range of 0 to 2 per cent.

Inflation, the stable real Swiss franc exchange rate in recent months and the ECB’s restrictive monetary policy are causing further increases in the SNB’s key interest rate. KOF expects to see this rate at 1 per cent by the middle of next year. Subsequently, the SNB should keep the interest-rate differential with the euro area more or less constant, which implies modest interest-rate cuts from the end of 2023 onwards (see chart G 5).

Focus on long-term inflation expectations

Long-term inflation expectations are responding to ongoing price pressures, which were initially seen as temporary. Market observers in the US currently expect to see an inflation rate of 3.6 per cent in five years’ time. This is well above the Fed’s inflation target. An upward trend can also be seen in the euro area although, at 2.2 per cent, inflation is now only slightly above the ECB’s target. Inflation in Switzerland is expected to increase to 1.25 per cent, although this is only marginally above the average of recent years. For central banks, inflation expectations are key indicators of whether price trends are being adequately considered by economic actors. A cross-country comparison should thus explain why interest rates in the United States are not only rising sharply at present but are also higher over the medium term.

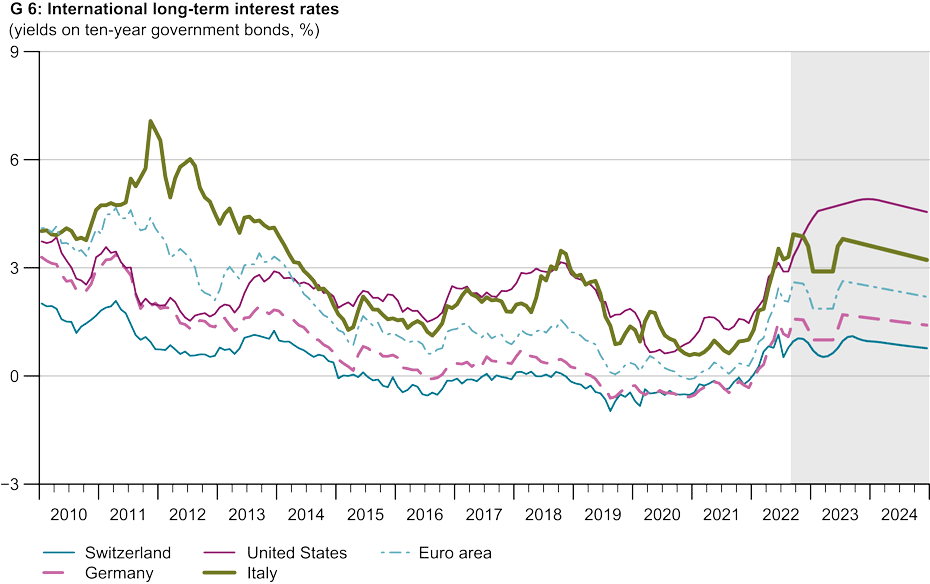

The rise in long-term inflation expectations is also causing an increase in international long-term interest rates (see chart G 6), as investors do not want to suffer any losses in real yields. This principle applies to more than just long-term government bonds. Ten-year mortgage rates in Switzerland, for example, are currently around 2 to 3 per cent, having previously remained just above 1 per cent since 2019. In line with the forecast weakening of international inflation dynamics, however, a gradual decline in long-term interest rates is again expected, with recessionary tendencies in the euro area likely to cause a brief dip next year. Although KOF continues to expect the nominal effective exchange rate to appreciate, this implies a constant real exchange rate owing to the inflation differential.

Contact

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland