How computerisation is transforming the Swiss labour market

New technologies are fundamentally changing the demand for labour in Switzerland and other countries. Is the Swiss workforce about to be replaced by robots, artificial intelligence and other digital technologies?

Technological progress has brought countless innovations – for example in the fields of medicine, power generation and product manufacturing – which improve our quality of life, and it is considered to be the main driver of a steadily growing economy. More recently, the vast improvement in digital storage capacity and the advent of internet communication have enabled the increasing computerisation and automation of our economies in general and the labour market in particular.

There is a lively debate among both the general public and academia about the impact of computerisation on the labour market. While technological progress has always displaced certain types of work and created others in the past, the net employment effect has generally been positive. However, there is widespread concern in society that this time things might be different and that computers, artificial intelligence, robots and the like could eventually displace human labour altogether.

Economics has identified two predominant mechanisms shaping the impact of computerisation on the labour market. The first is that digital technologies generally increase demand for workers with higher levels of education; the higher the level of employees’ qualifications, the more likely they are to expect (even) better wages and employment prospects in a computerising world of work (Katz & Murphy 1992). The second postulates that digital technologies can be used to ‘automate’ routine tasks in particular, i.e. those that are carried out according to clearly defined instructions and procedures. Accordingly, workers who perform a high proportion of such routine activities – e.g. factory workers who sort and store products, or office workers who keep and check balance sheets or registers – would forgo job opportunities (Goos, Manning & Salomons 2014). Since such routine jobs generally pay middle incomes in the United States, for example, and a significant decline in such jobs has been observed there since the early 1990s, this mechanism is also often associated with the shrinking of the middle class and growing inequality.

Sharp decline in manual and cognitive routine jobs

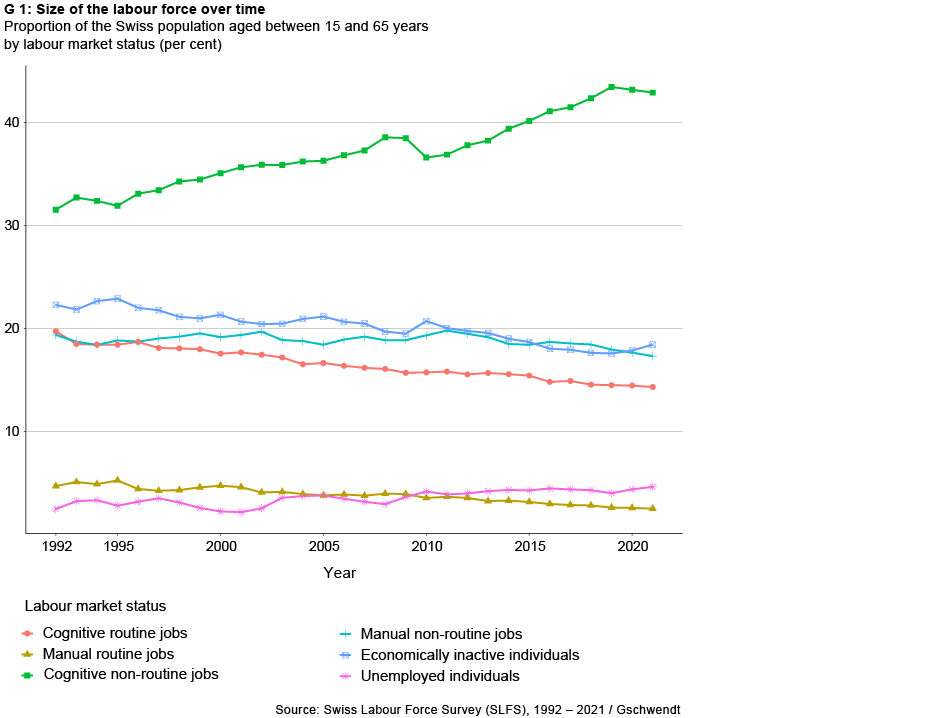

Both of these mechanisms of computerisation can be observed in Switzerland. The proportion of employees working in routine jobs has constantly declined since the 1990s. In addition to the routine share of occupations, a distinction can also be made between jobs that are mostly manual and those that are mostly cognitively demanding. If Swiss workers are also classified according to this distinction, it becomes apparent that fewer and fewer employees are working in cognitively demanding routine jobs. This can be seen in chart G1, which shows how the proportions of the employed, unemployed and economically inactive have evolved over time. Economically inactive persons are individuals who are not working and – in contrast to the unemployed – are not looking for a job, such as full-time students and househusbands

It is also evident that, even before the turn of the millennium, only a small proportion of the Swiss workforce did manually intensive routine jobs, and this share has since decreased even further. In contrast, the proportion of employees working in cognitively demanding jobs that involve only few or no routine activities and tend to require a higher level of education has increased significantly and consistently. While the share of manual non-routine occupations has hardly changed, there has been a notable decline in the proportion of the economically inactive, which can largely be attributed to the greater employment of women.

How has this structural change taken place? An analysis of labour market trends (Gschwendt 2022) shows that, fairly often, routine workers have neither ended up more unemployed nor have they retired. However, fewer and fewer workers have found new employment in routine occupations after previously working in manual non-routine jobs that tend to be lower paid, for example because there were fewer routine jobs to fill. Such workers are thus finding it increasingly difficult to move into routine jobs that tend to be better paid. In addition, the tendency to enter the labour force doing a cognitive routine job has decreased, especially among individuals with low or moderate levels of education and among middle-aged people.

The growth in employment in cognitively demanding non-routine occupations as far back as the 1990s, on the other hand, was largely due to young and well-educated people entering the labour market. This growth has continued to the present day, interrupted only by the financial crisis of 2008, and is mainly caused by an increase in the number of people with tertiary education who are finding vacancies in these occupations. As Beerli et al. (2022) show, immigrants from abroad make up a significant proportion of these well-educated entrants.

In Switzerland there are no signs of higher unemployment being caused by computerisation

In the US and the UK, computerisation has led to an increase in workers previously employed in routine jobs becoming unemployed, ending up in lower-paid service jobs or even dropping out of the workforce altogether. There are very few signs of such disturbing trends in Switzerland. Whereas these two Anglo-Saxon countries have highly liberalised labour markets and a restrained welfare state, Switzerland has stronger labour market institutions and a more extensive welfare state, all of which inhibit the growth of low-paid service jobs. In addition, Switzerland’s dual education system gives workers greater flexibility to respond to changing employer needs in the wake of computerisation.

So far the Swiss workforce has shown itself to be fairly resilient in the face of the fundamental structural changes being driven by computerisation. Demand for human labour in Switzerland remains especially high. However, the education system in general – and vocational education and training in particular – bears a major responsibility to prepare those entering the workforce. Even prospective employees without higher-education qualifications require skills that will enable them to survive in a labour market that will continue to computerise in the future.

Literature

Beerli, A., R. Indergand, & J. S. Kunz (2022): The supply of foreign talent: how skill-biased technology drives the location choice and skills of new immigrants. Journal of Population Economics, 1-38.

Gschwendt, C. (2022): external pageRoutine job dynamics in the Swiss labor market. Swiss Journal of Economics and Statistics, 158(1), 1-21.

Goos, M., A. Manning, & A. Salomons (2014): Explaining job polarization: Routine-biased technological change and offshoring. American economic review, 104(8), 2509-26.

Katz, L. F. & K. M. Murphy (1992): Changes in relative wages, 1963–1987: supply and demand factors. The quarterly journal of economics, 107(1), 35-78.

Contact

Universität Bern

Department Volkswirtschaftslehre, Forschungsstelle für Bildungsökonomie

Schanzeneckstrasse 1

3001

Bern

Schweiz