How population growth and ageing may foreshadow poverty alleviation in low- and middle-income countries

KOF Bulletin

The world is growing older. According to the World Bank, the percentage of the global population aged 65 and above nearly doubled from 1960 to 2020. While developed countries are struggling with the consequences of population ageing, less-developed countries still stand to benefit. But how could population ageing spur economic growth in less-developed countries, and how can policymakers maximise its benefits?

Population growth has often been viewed as being detrimental to income per capita. In 1798, Robert Malthus argued that humanity would remain stuck in poverty indefinitely because any increase in income generated by new technology would lead to exponential population growth that eventually nullifies all previous income growth.

Subsequent empirical work highlights the fact that the direct role of population growth in determining income per capita is extremely limited. More recently, academic research has moved towards analysing the effects of the population age structure on economic development. The key idea behind this literature is that once the fertility rate begins to decline and life expectancy increases, there is a brief period of time during which there are many workers and few children and elderly individuals: the so-called Demographic Window of Opportunity. During this window, policymakers have unique opportunities to spur their economies’ growth rates, i.e. to obtain a Demographic Dividend.

The Demographic Window of Opportunity: concept and definition

Conceptually, this approach subdivides the Demographic Window of Opportunity into four stages.

Historically, all countries were stuck in an equilibrium with high birth and death rates and low incomes. For instance, according to the OECD Clio Infra database1, Germany’s gross domestic product (GDP) per capita was 1,872 US dollars in the year 1500. A few hundred years later, in 1800, Germany’s GDP per capita was still very similar at 1,572 dollars. Despite this decline in income per capita, the population grew steadily from 12 million inhabitants in 1500 to 18 million in 1800. This is the first stage, or the Malthusian era: almost all technological development translated into population growth (higher fertility and lower death rates) and little or none into per-capita income growth. Today, many less-developed regions remain stuck in this first stage. For instance, Niger’s GDP per capita is currently only 1,288 dollars according to the World Bank, while in 1950 it was 1,200 dollars according to the OECD Clio Infra database.

In the second stage – conditional on good governance such as well-developed property rights – economies of scale come to fruition as societies with larger populations generate more ideas and segments of the population can specialise in idea production, allowing for higher-quality innovation. We begin to break free from the Malthusian trap, as technological progress begins to exponentially increase, outpacing population growth. This is also known as the Boserupian model.

In the third stage we truly depart from Malthus, as fertility rates begin to decline despite rising incomes. As our economic output becomes increasingly complex, we require education for workers to properly operate the technologies available. This increase in human capital accelerates economic growth, while simultaneously raising the opportunity cost of having children. Women delay their decision to have children for educational or career-building purposes, and households decide to have fewer children, allowing them to invest in the education of their children. This mechanism also pushes more women back into the labour market. Population size continues to grow, though now at an increasingly slower pace.

In the final stage, population growth slows down or even starts to decline as fertility and death rates are at similarly low levels. During this stage, dependency once again rises as there are increasingly more elderly individuals. Economic growth slows down, though at much higher levels of GDP per capita. Today, many countries have transformed into high GDP per capita levels with low population growth. However, concurrently, there are still many countries where GDP per capita remains low while population growth remains high.

Existing ways of classifying whether regions are within the Demographic Window of Opportunity are somewhat rudimentary. For instance, the UN Population Department classifies a region as being within the Demographic Window of Opportunity if less than 30 per cent of the population is under 15 years old and less than 15 per cent of the population is over 64 years old, or if the working-age population (15 to 64) is greater than 55 per cent of the population. To obtain a more nuanced picture of the window, this analysis uses the following classification scheme:

1. Traditional phase (> 40 per cent under 15 and < 15 per cent over 64 – think stage 1),

2. Pre-window phase (30 to 40 per cent under 15 and < 15 per cent over 64 – think stage 2),

3. Early-window phase (25 to 30 per cent under 15 and < 15 per cent over 64 – think stage 3),

4. Mid-window phase (20 to 25 per cent under 15 and < 15 per cent over 64 – think stage 3),

5. Late-window phase (< 20 per cent under 15 and < 15 per cent over 64 – think stage 3),

6. Post-window phase (> 15 per cent over 64 – think stage 4).

The Demographic Window of Opportunity across the globe

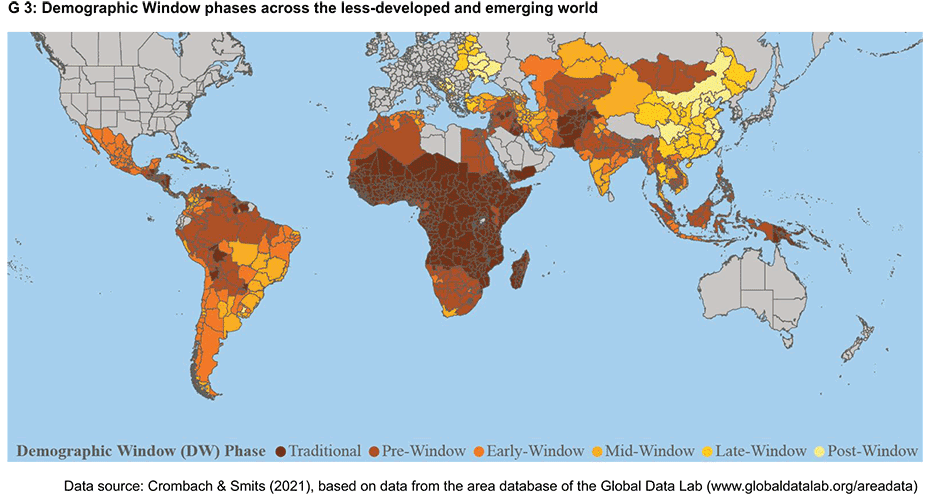

There are many differences in terms of Demographic Window phases both between countries and regions and sub-nationally within the countries themselves (see Figure G 3). China is the only low- or middle-income country with some regions having gone through the Demographic Window, while its northern neighbour, Mongolia, is mostly still in its pre-window phase. India faces more differences within its borders: most of the north is lagging behind in its pre-window phase, while most of the south is enjoying the gains of the mid-window phase. The MENA region shows substantial between-country diversity: many regions in Turkey, Tunisia and Iran are in the early-window phase, while others remain in the pre-window or traditional phases. In South America, countries such as Brazil and Argentina are leading in terms of the Demographic Window.

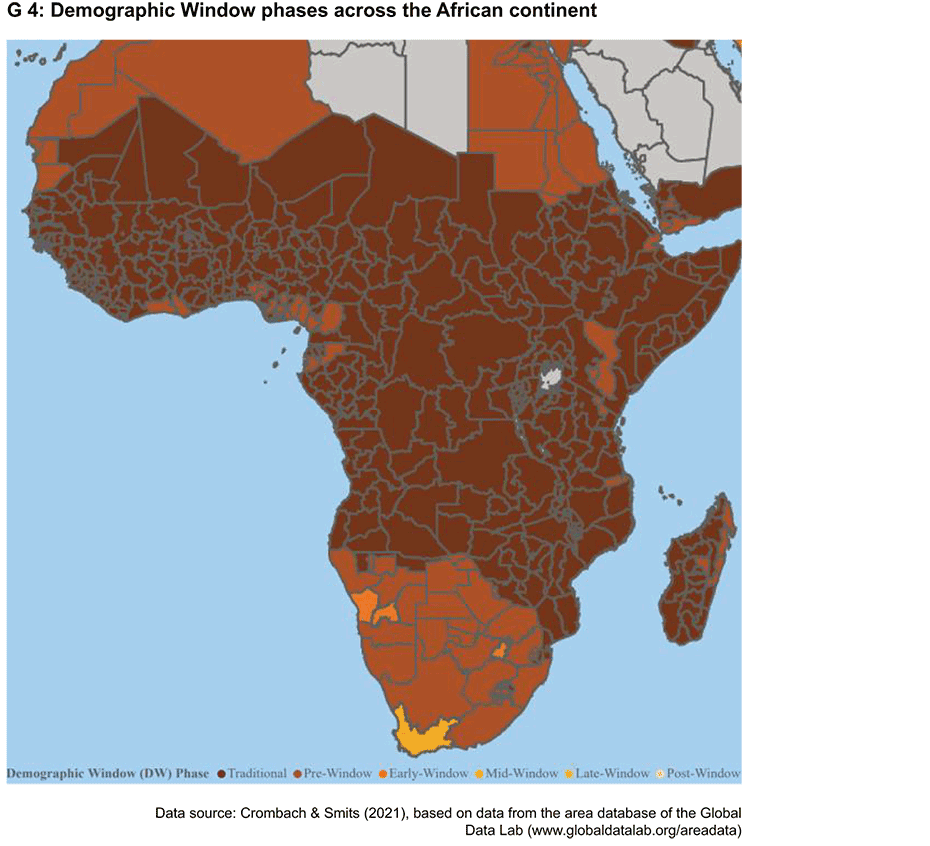

The situation in Sub-Saharan Africa is quite unique and bleak. While some regions, mostly in the south, appear to be past the traditional and pre-window phases, much of the central African region remains in the traditional phase. Across Africa as a whole, the picture remains similar, with only a limited number of regions in the south, around the Gulf of Guinea and a few other places that are in a later stage (see Figure G 4).

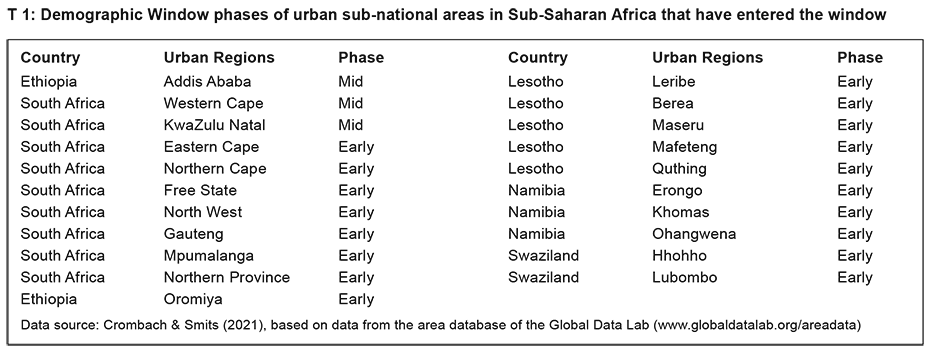

There appears to be a spark of hope, however. The Demographic Window is opening in more places than one would expect based on Figure 2 (see Table T 1). While Botswana is in the pre-window phase, for instance, the urban area of one of its regions — South-East — is already in the mid-window phase. And, lastly, while Ethiopia is in the traditional phase, the country’s capital Addis Ababa is already in the mid-window phase. This data highlights the importance of a sub-national approach in dealing with demographic changes, as population age structures vary substantially within countries.

The Demographic Dividend and its determinants

While the Demographic Window is conducive to economic growth, it may not necessarily increase such growth. The window is associated with potential benefits and risks, hence ‘window of opportunity’. If a government can exploit the benefits while retaining the risks, it can reap a Demographic Dividend, i.e. the additional economic growth associated with the Demographic Window of Opportunity.

The literature describes benefits associated with the above window that go beyond having more workers available. Firstly, given that workers are much more likely to save than children or the elderly, savings will rise owing to the increase in the working-age share of the population. Savings will also grow because of the greater life expectancy of the population during the Demographic Window. This additional influx of savings lowers the interest rate, allowing for cheaper investments in the credit markets. Secondly, human capital can increase substantially as (i) the greater life expectancy raises the returns to education, (ii) households are better able to invest in education for their children as they have fewer of them while enjoying higher incomes, and (iii) governments are also better able to invest in education for each child as there are fewer children and they receive higher tax revenues owing to the larger share of workers. These mechanisms may give rise to long-term per-capita output growth that exceeds the simple growth associated with having more workers available.

Nevertheless, there are risks associated with having a large share of working-age individuals in the population. Firstly, there might be civil unrest and crime because of high unemployment rates if the labour market is unable to absorb the large increase in the labour supply. Such factors may deter (foreign) investment. Secondly, the credit markets must be sufficiently developed to efficiently convert saving into investment. Thirdly, governance must be conducive to economic growth during the window by ensuring low levels of corruption and efficient governance. Corruption may reduce access to public services such as education and health, while poor governance can lead to under-investment in key sectors – all factors which diminish productivity. Failing to account for these risks might plunge an economy into the middle-income trap: a situation where the country is no longer competitive in the manufacturing sector owing to its higher wages but, equally, it is not yet competitive in the knowledge economy.

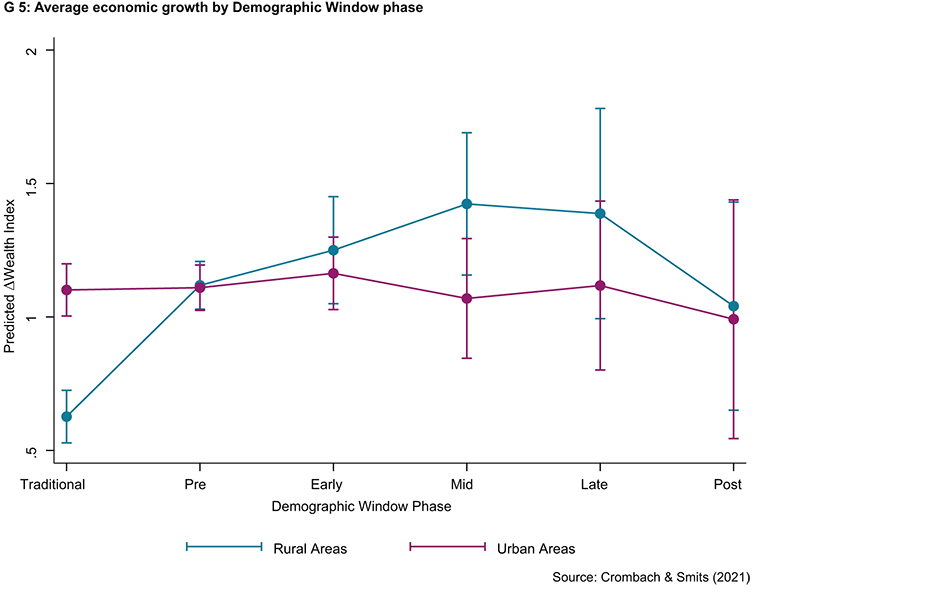

Although these mechanisms all sound reasonable, there was little data available to determine which factors were empirically relevant. Crombach & Smits (2021) used data on 1,921 sub-national areas in the less-developed world as part of a multi-level analysis to investigate which of these reaped a larger Demographic Dividend. Strikingly, all benefits are achieved in rural areas. The population age structure offers virtually no benefits for economic growth (proxied by improvements in material well-being according to the Global Data Lab’s International Wealth Index) in urban areas (see Figure G 5). This could indicate that rural areas are better able to reap the benefits of the window as they were already lagging behind in terms of labour markets, credit markets and governance or, rather, urban areas are less able to balance the risks associated with the window, completely nullifying any potential income growth.

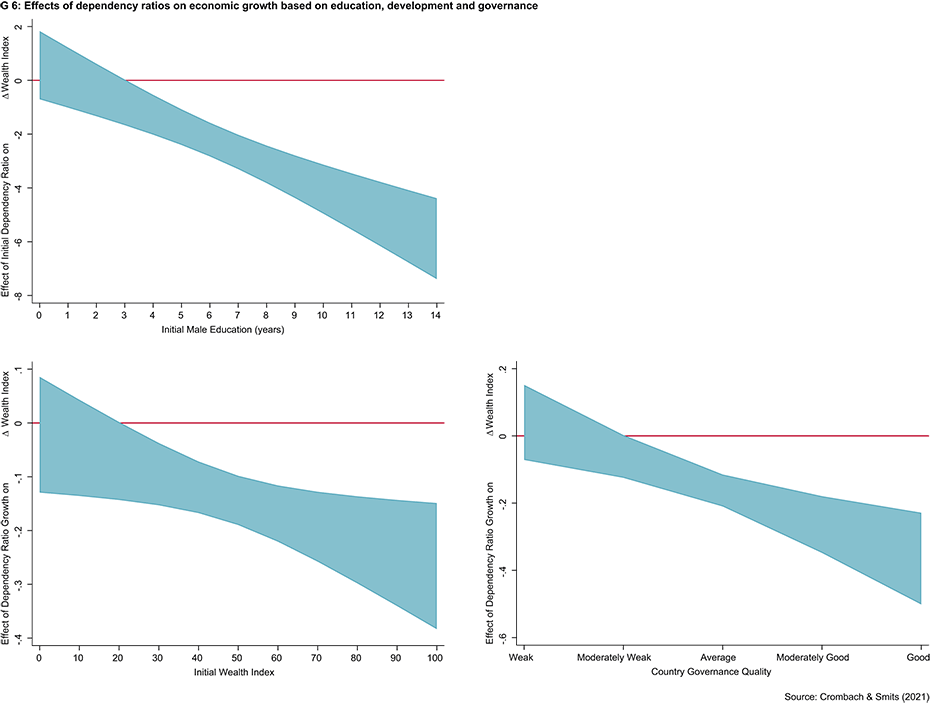

As countries move through the window, the dependency ratio (share of the young and elderly divided by the share of workers) declines while economic growth is expected to improve (negative correlation). The estimates in Crombach & Smits (2021) indicate that regions that invested in education in their traditional or pre-window phases have reaped a larger Demographic Dividend (see Figure G 6). Additionally, the dividend is larger in regions that already managed to attain a higher level of development before entering the window. Both results indicate that it is important for local policymakers to make key investments just before the opening of the window to achieve the maximum Demographic Dividend. We can also see that country-level governance has a positive impact on the Demographic Dividend. In terms of credit markets, counter-intuitively, we find that countries with an inferior financial performance have more regions with higher growth during the window (not visualised), which goes against the credit market mechanism of higher saving and lower investment.

In sum, the Demographic Window of Opportunity is a period during which countries move from a high-fertility, high-mortality-rate situation to a low-fertility, low-mortality-rate situation. Countries generally greatly improve their economic conditions during this window. While most countries in the world have either already passed through or are currently within the Demographic Window of Opportunity, most countries in Sub-Saharan Africa have yet to enter the window. These areas can benefit from using the empirical results in this article, which show that rural areas with higher levels of education and development in the traditional or pre-window phases reap a larger Demographic Dividend than other areas. At the country level we once again highlight the need for good governance, while nuancing the importance of economic development.

-------------------------------------------------------

1 external pagehttps://clio-infra.eu/Indicators/GDPperCapita.htmlcall_made

Contact

Professur f. Wirtschaftsforschung

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland