How economic research differs from the natural sciences

KOF Bulletin

In his book ‘False Feedback in Economics’, KOF economist Andrin Spescha critically examines the methodological and philosophical foundations of economics and other social sciences.

Considering the rapid advances achieved in certain natural sciences, the progress made in economics and other social sciences seems much more modest in comparison. Applied research in the natural sciences, for example, is providing us with ever better computers, robots, software and now even things that were thought to be impossible, such as self-driving cars. The natural sciences have also managed to develop a coronavirus vaccine within a very short space of time. In economics, on the other hand, it is harder to see obvious signs of progress, because there are always at least two differing, contradictory research positions on almost every subject – from the minimum wage and monetary policy to development economics. Although methods change over time, it is not clear whether economics can increasingly better reflect economic reality through its research papers.

Feedback in the natural sciences is clearer and more direct than that in the social sciences

In his book ‘False Feedback in Economics: The Case for Replication’, KOF economist Andrin Spescha attributes this difference between the natural sciences and economics to the fact that the natural sciences mostly deal with physical objects and technologies. Working with physical objects is fundamentally different from working with data. Physical objects enable true feedback, which means that one always knows whether and how, for example, a newly developed technology is really better than previous ones. When applied researchers work on a concrete object such as a robot, they know whether their approach to improving the object works or not. Their direct physical interaction with the robot continuously produces true feedback on their work. Applied scientists can thus achieve progress step by step, which then translates into better technologies in the aggregate.

The data world in economics, on the other hand, is very susceptible to false feedback. This does not mean feedback from peers, but the feedback researchers receive from data analysis and evaluation. Empirical studies in economics too often provide incorrect answers to the their questions. Of course, this is far from true for all studies. However, it is difficult even for experienced researchers to spot the studies that provide true feedback, i.e., studies that accurately reflect reality. Consequently, researchers do not know exactly where they stand with their inquiries and it becomes difficult to make any progress. “Knowledge can only grow if researchers can rely on true feedback; they need true answers about how their proposed hypotheses relate to empirical reality,” writes Spescha. Only this way it becomes clear in which direction science must move in order to make progress. The question of why false feedback often occurs in economics and how this situation can be improved is addressed by Spescha in his book, which is published in the Routledge series ‘Studies in Economic Theory, Method and Philosophy’.

Comparing different studies is often difficult or even impossible in economics

What makes empirical social research – whether in economics, political science or sociology – so complex is that each study is based on a huge number of (mostly implicit) side assumptions. In addition, different studies operate with different empirical approaches and in different research environments, so it is often difficult or even impossible to compare studies in terms of their truth content (the American philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn coined the term ‘incommensurability’ for this). Thus, in the case of contradictory empirical studies, one side is often not visibly closer to reality than the other. Unlike in the natural sciences, false theories are therefore difficult to disprove and reject according to the principle of ‘trial and error’ which, for the philosopher of science Karl Popper, characterises the ideal science and is also the key element in progress.

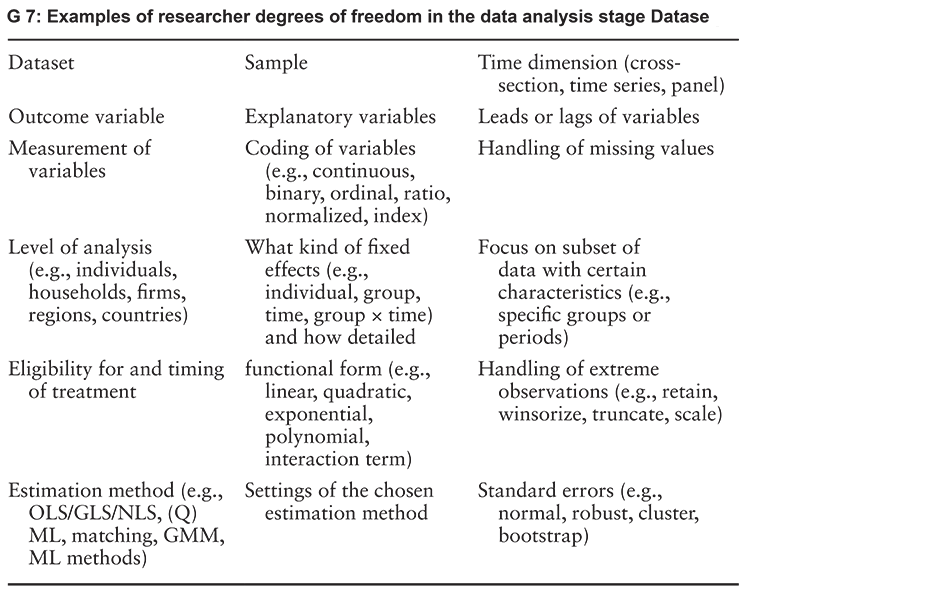

The main problem that creates false feedback in economics (and other empirical social sciences), according to Spescha’s analysis, is the large number of options that researchers have in choosing their research methods and data analysis. As Chart G 7 shows by way of example, research approaches can vary in a wide variety of dimensions in terms of data analysis alone. As in the short story ‘The Garden of Forking Paths’ by the Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges, there are numerous forking paths in research projects, where researchers can decide which direction to take methodologically, often without having to explain the reasons for their decision. Consequently, researchers have a great deal of leeway at each of the forks shown in Chart G 7. However, each decision can potentially have a big impact on the eventual outcome, so the findings can vary considerably depending on the individual researcher and his or her approach.

These 18 types offorks appear in most empirical studies in the social sciences, although the table is far from complete. Given already these 18 forks in the table, for example, with only three options per fork, 318 = 378,420,489 different research paths can be followed, making it enormously difficult to compare empirical studies. This means that a social scientist’s hypotheses cannot be tested in isolation, because they are embedded in a network of implicit assumptions and beliefs (Duhem-Quine thesis).

Researchers should put more emphasis on replicating studies

Building on these considerations of philosophyofscience, Spescha argues in his work for more transparency in empirical economic research. Instead of just producing polished academic papers, economists should also publish their data and programming codes so that other researchers can try to replicate their studies. Only this way can implicit methodological decisions be understood and questioned. This is more valuable than endlessly authoring new studies, as is common academic practice today, writes Spescha in his concluding chapter. “Instead of producing a constant stream of scientific papers that are often new only on the surface, we would do better to focus our efforts on getting the really best studies right. We would need to vary the design of these most important studies in a systematic and meaningful way so that we gain insights into their strengths and weaknesses.” If we succeed in generating robust and true feedback on our questions in this way, progress will also return, he claims.

Contacts

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland

KOF Bereich Zentrale Dienste

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland