Poorer households particularly affected by rising healthcare costs

- Inflation

- KOF Bulletin

- Health care

Directly paid healthcare costs in Switzerland decrease as a share of income as income increases, whereas in other countries it is typically the other way round. This is due not to rising healthcare costs but to the way healthcare expenditure is funded.

Part of Switzerland’s self-image is the conviction that the Swiss healthcare system is expensive but otherwise exemplary. A quick look at the international statistics of the World Bank shows that this is only true in one re-spect. Among the 38 OECD countries, total healthcare expenditure as a share of GDP is in fact only higher in the United States than it is in Switzerland, and the same applies to healthcare spending per capita. 1 The key healthcare indicators show that Switzerland ranks second behind Norway in terms of the number of nurses and midwives relative to its population, but it is only a middle-ranking country in terms of physician density (12th) and the number of hospital beds (13th), the latter having become painfully evident during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Switzerland also differs significantly from other rich countries in its financing of healthcare expenditure. In these economies, state or quasi-state funding and service provision play a much greater role than they do in this country. Switzerland comes last in terms of the state’s share of total healthcare expenditure, which amounts to just over 30 per cent. This is only about half the OECD average and is politically desirable. In fact, Switzerland comes way ahead of all others in terms of its private healthcare costs (including health insurance) as a share of total costs (almost 70 per cent) and in terms of its direct private healthcare costs per capita (deductibles, co-payments and uninsured healthcare costs). In addition, Swiss healthcare prices were 1.4 times higher than the EU average in 2000 and 2.3 times higher in 2020. 2

Health insurance premiums have increased more than general prices

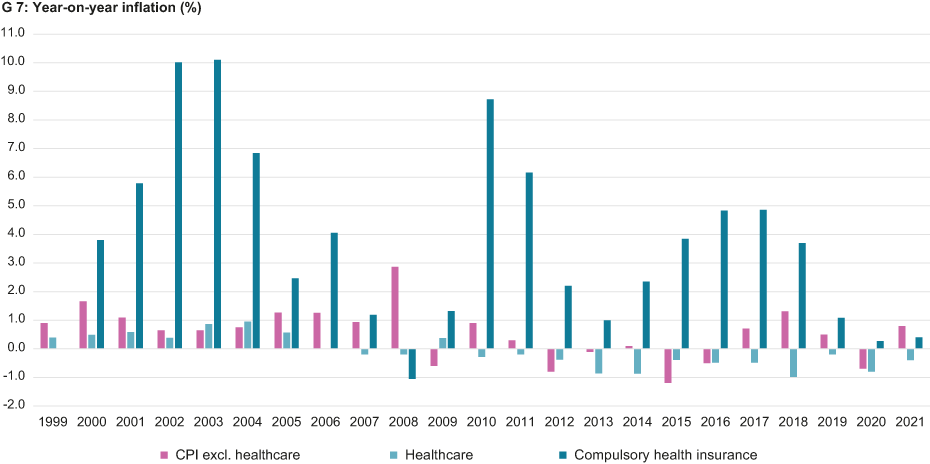

It is therefore not surprising that the level of private healthcare spending in Switzerland is a highly political issue. Since compulsory health insurance (OKP) was introduced in 1996, premiums have risen much more sharply than the general prices reflected in the National Consumer Price Index (CPI); and, since premiums are differentiated according to the level of risk rather than income, lower-income households in particular are suffering an erosion of their purchasing power (see Chart G 7).

The impact that inflation has on households in Switzerland is determined by domestic price trends. However, high relative prices in certain expenditure categories ensure that this spending accounts for a large proportion of total expenditure, which means that such price changes can have a dramatic impact on financially worse-off households without this being reflected in the CPI statistics.

Unfortunately, the Swiss Federal Statistical Office has not published inflation statistics for various socio-economic groups since 2003, and the level of OKP premiums is not included in the CPI. However, the inflation in healthcare costs compared with the CPI (excluding this main group) and the health insurance premium index provide a starting point for a general overview that shows the annual levels of premiums since 2000. The inclusion of the household budget survey conducted since 2000, which breaks down its results by household type, has enabled the following findings to be identified:

- The levels of healthcare costs according to the CPI have differed from the overall index over the last two decades. The cumulative change in the former over the period from 1999 to 2021 was -2.4 per cent (annual average of -0.15 per cent), whereas for the CPI excluding the healthcare sector it was 12.4 per cent (annual average of 0.5 per cent). Over the same period, however, the index for the OKP shot up by 125.7 per cent (annual average of 3.8 per cent). As the chart below shows, this is not due to individual outliers: these differences are typical.

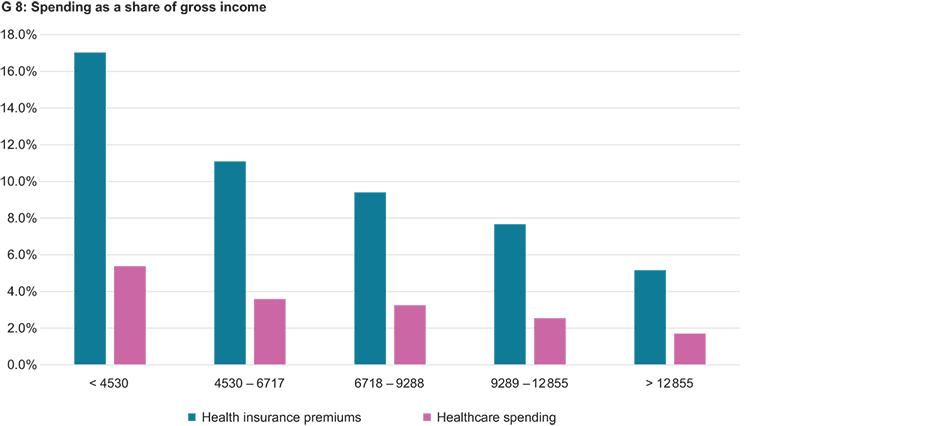

- According to the latest available breakdown of the household budget survey (2015 to 2017), the typical household’s direct healthcare expenditure as a proportion of their gross income was 2.6 per cent, the relevant spending on the OKP was 6.5 per cent and a further 1.4 per cent went on supplementary insurance, making a total of 10.5 per cent. For the financially most heavily burdened households (couples aged 65 and over), however, the relevant share accounted for by total healthcare costs was 2.8 times higher at 29.9 per cent, while for the least financially burdened households – couples aged under 65 in the highest of five income brackets (more than CHF 15,731 per month) – the relevant proportion was 5.0 per cent, which is less than half the amount for the average household. In general, these proportions increase with age and are higher for lower-income households. The number of children living in a household, on the other hand, shows no consistent effects on health expenditure as a share of the household budget.

Growing burden on older and poorer households

These findings are notable. We know from international research that older and poorer households are facing higher inflation rates than the average household owing to rising healthcare costs. Although this has been true for the last 20 years in Switzerland, it is driven solely by health insurance premiums, as the healthcare costs paid directly by households have tended to rise less sharply than the CPI. The inclusion of healthcare costs in the CPI, which does not include the OKP, thus conceals the growing financial burden on the oldest and poorest as a result of the increase in health insurance premiums.

It is also striking that directly paid healthcare costs as a share of income in Switzerland decrease as income increases, whereas in other countries this is typically the other way round (see Chart G 8).3 The distribution of spending in Switzerland is dominated not by the ability to afford a larger proportion of healthcare expenditure in higher-income household budgets but by payments of a compulsory nature (deductibles, co-payments) and services not covered by the OKP in this country (such as dental costs), which means that the less well-off households have to spend a larger share of their incomes on this than the better-off do. Although this is less a focus of healthcare policy debates in Switzerland than the regressive financial burden of income-independent health insurance premiums, it is again the result of politically desirable healthcare funding. Whether this is right from a socio-political point of view should also be discussed.

______________________________________

1 These and the following international comparative figures were taken from the World Bank’s external pageonline data portalcall_made on 14 January 2022 and relate to the most recent fully recorded year (2018). The pandemic is therefore not yet reflected here.

2 external pageInternational comparisoncall_made by the BFS.

3 For Germany see list external pageherecall_made.

A previous version of this article appeared in the February 2022 issue of Konsumentenstimme published by the internet service provider comparis.ch external pageherecall_made.

Contact

KOF Konjunkturforschungsstelle

Leonhardstrasse 21

8092

Zürich

Switzerland